by Sebastien Luc Delprat

‘In the fields of observation, chance favours only the prepared mind.’ 1

In these pandemic times, I couldn’t find a more appropriate way to begin my update on Moriondo’s espresso machine quest than to cite Louis Pasteur (a French scientist who worked on vaccines at the end of the nineteenth century). The word chance describes both luck and randomness, but there is a subtle difference between the two: If random events happen all the time, it will only appear as luck to someone who is expecting something out of it.

Indeed, because ‘chance favors the prepared mind’, every discovery contains a portion of chance. That is the case in science as well as in the technological evolution of coffee makers (which was mostly driven by science during the nineteenth century), and it also happened to me as I was searching for ‘pieces of the puzzle’ relating to the birth of espresso. And, yes, the pandemic has something to do with it, as it gave me a lot of spare time to spend again on that story … This new opus also has a lot to do with chance, since Jeremy Challender from Barista Hustle contacted me right after I made some determinant finds in my specific field of observation.

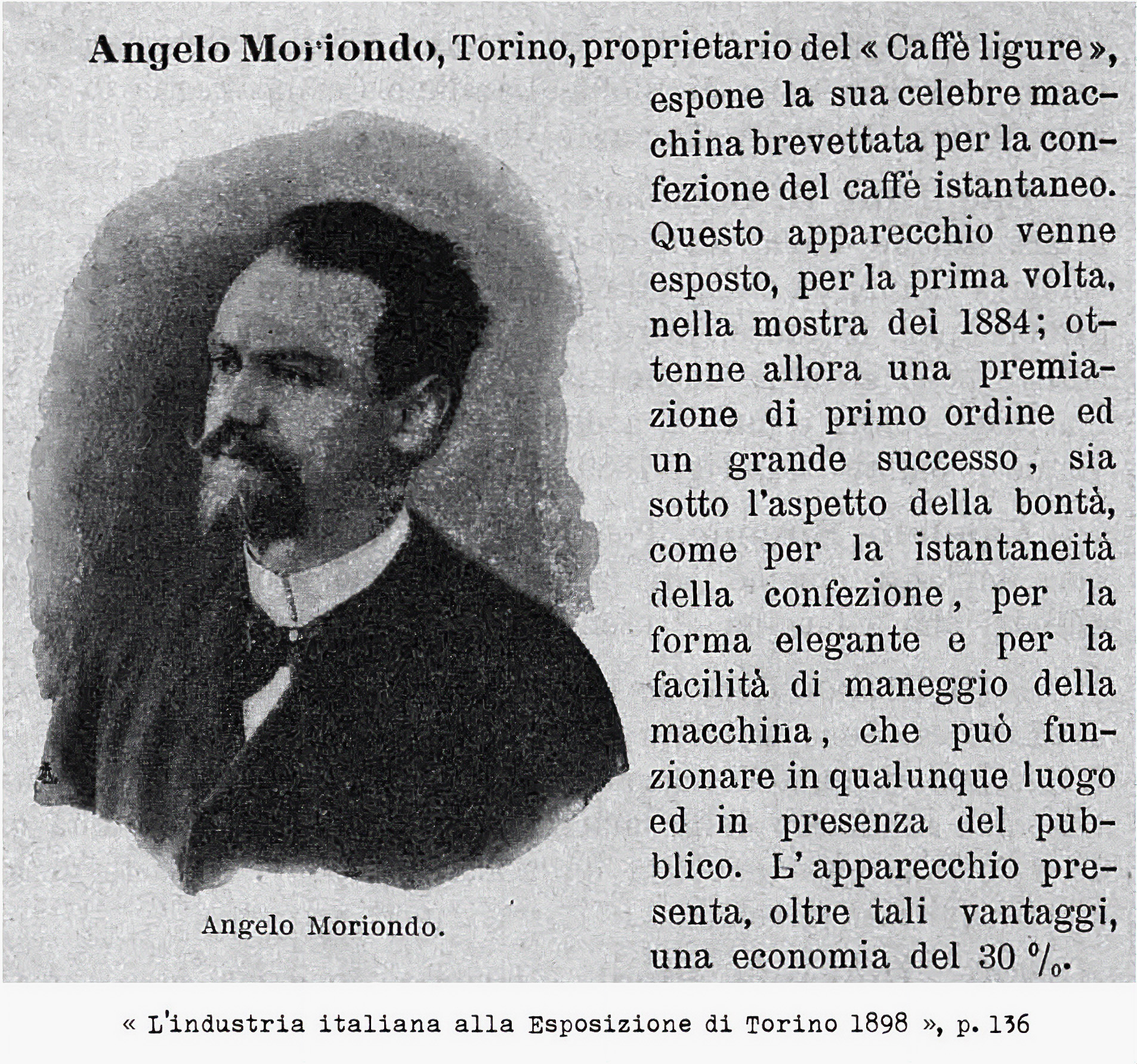

Portrait of Angelo Moriondo published in the official catalog of the 1898 Turin exhibition. It was most likely made during the previous exhibition, in 1884, since he looks much more 33 than 47 years old in the portrait.

Portrait of Angelo Moriondo published in the official catalog of the 1898 Turin exhibition. It was most likely made during the previous exhibition, in 1884, since he looks much more 33 than 47 years old in the portrait.

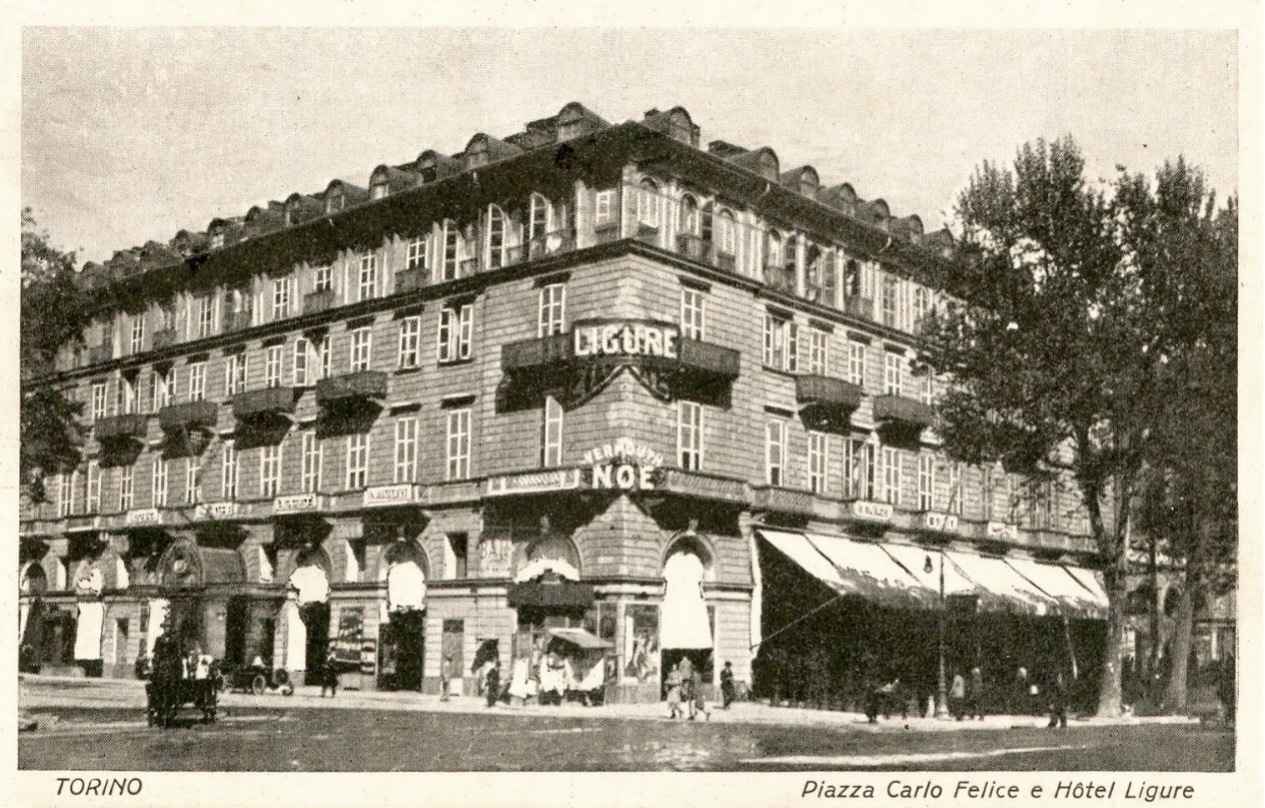

Postcard showing the Hotel and Caffè Ligure, in Turin, which Angelo Moriondo managed at the end of the nineteenth century. Beginning in 1884, he served ‘Istantaneo’ coffee there on his acclaimed machine.

Postcard showing the Hotel and Caffè Ligure, in Turin, which Angelo Moriondo managed at the end of the nineteenth century. Beginning in 1884, he served ‘Istantaneo’ coffee there on his acclaimed machine.

Angelo Moriondo: A Viral Obsession

Nearly ten years ago, when I began doing research on the espresso revolution, only one solid reference book on the subject was available: Coffee Floats, Tea Sinks from Ian Bersten (1993). Bersten discovered that, contrary to the widespread version of the story, Angelo Moriondo was the person who invented the ‘express’ coffee machine (meaning instantly delivering coffee, thanks to steam pressure) … seventeen years before Bezzera and Pavoni. He made this incredible find by exhuming a patent from the French archives (which are, unlike Italian ones, properly referenced and easily accessible). He also reported the existence of another Moriondo patent from 1910, well after Bezzera’s and Pavoni’s debut.

Franco Capponi, who wrote an excellent book for La Victoria Arduino, continued Bersten’s work and found the 1884 original Italian patent from Moriondo, plus an addition to it that had been filed in the same year. He reported multiple facts about Moriondo’s personal life, such as that Angelo’s family members founded the Moriondo & Gariglio chocolatery (which still exists today); Moriondo owned the Caffè Ligure in Turin (sited in a famous hotel located in front of the Torino central train station); Moriondo was a vermouth producer; and he lived from 1851 to 1914.

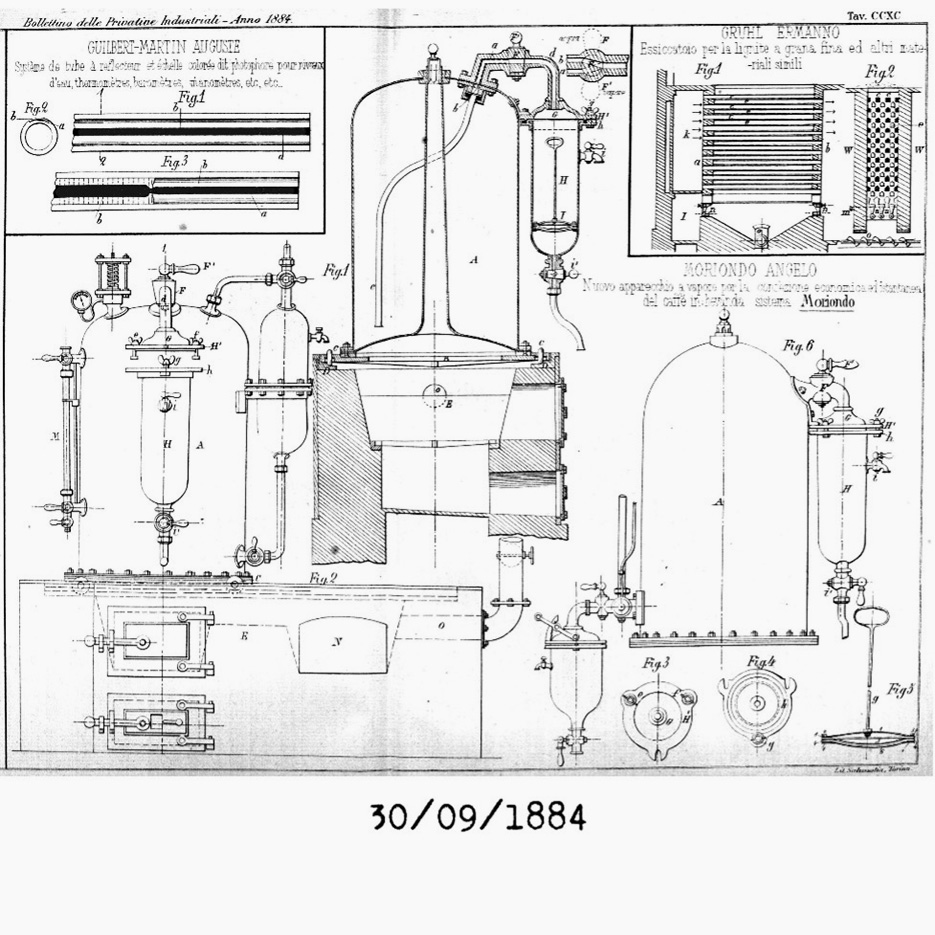

Drawings from the first two Angelo Moriondo patents (‘Nuovi apparecchi a vapore per la confezione economica ed istantanea del caffè in bevanda – Sistema A. Moriondo’), as they originally appeared on the 1884 Bolletino delle privative industriali.

When I began my research on Angelo Moriondo, twenty years after Bersten, most of the histories of espresso available were still reporting Luigi Bezzera and Desiderio Pavoni as the inventors of the ‘express’ machine, illustrating that claim by showing the famous picture of their American bar at the 1906 Milan Fair … and hence ignoring the work by Bersten and Capponi. With the availability of online documents, I was lucky enough to find additional information about Moriondo: an unknown portrait of the young Angelo (see the first illustration above), revealing his presence at the 1898 Turin International exposition; the two complete French patents from 1884 and 1885; the one from 1910; and lots of anecdotes about his life as a bartender and, later, as a coffee roaster in Turin. (Did you know that he was a fan of music and that a polka was composed to honor his invention?)2

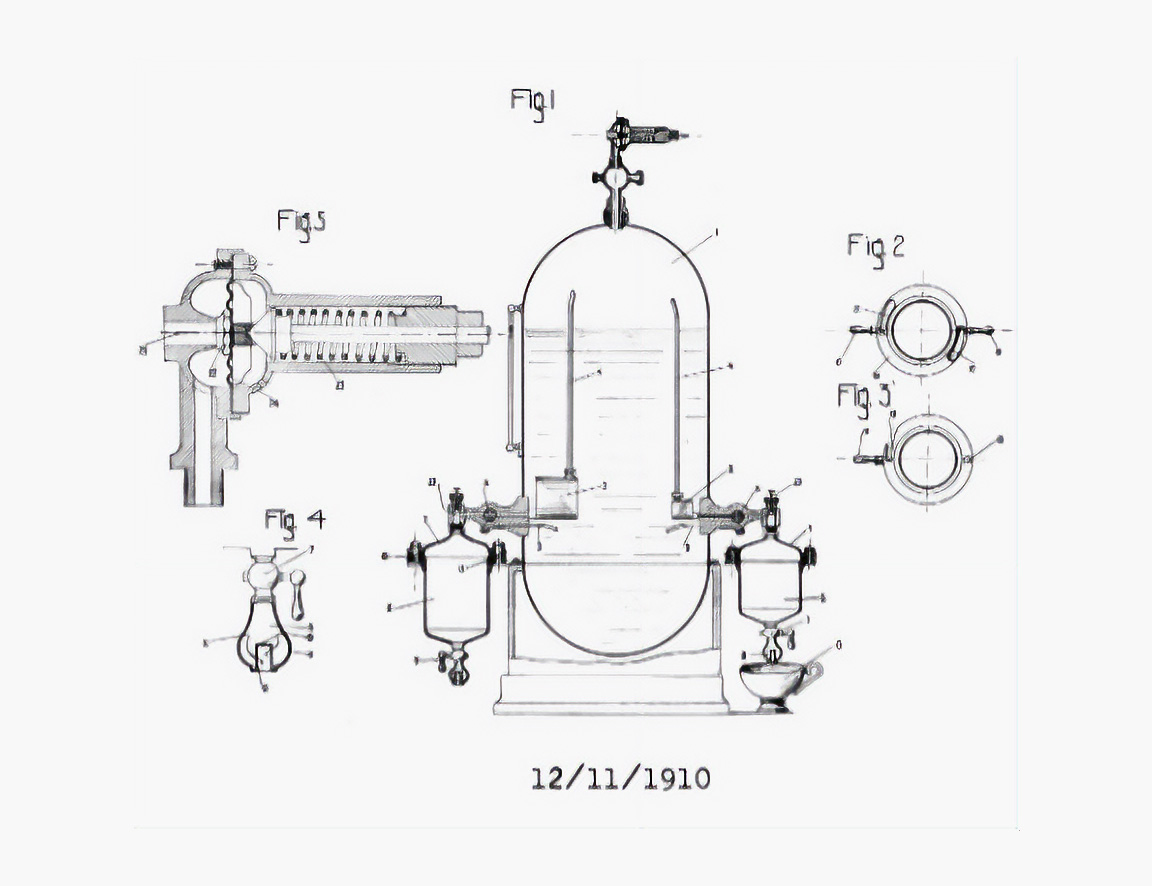

Original drawings from Angelo Moriondo’s 1910 patent.

Original drawings from Angelo Moriondo’s 1910 patent.

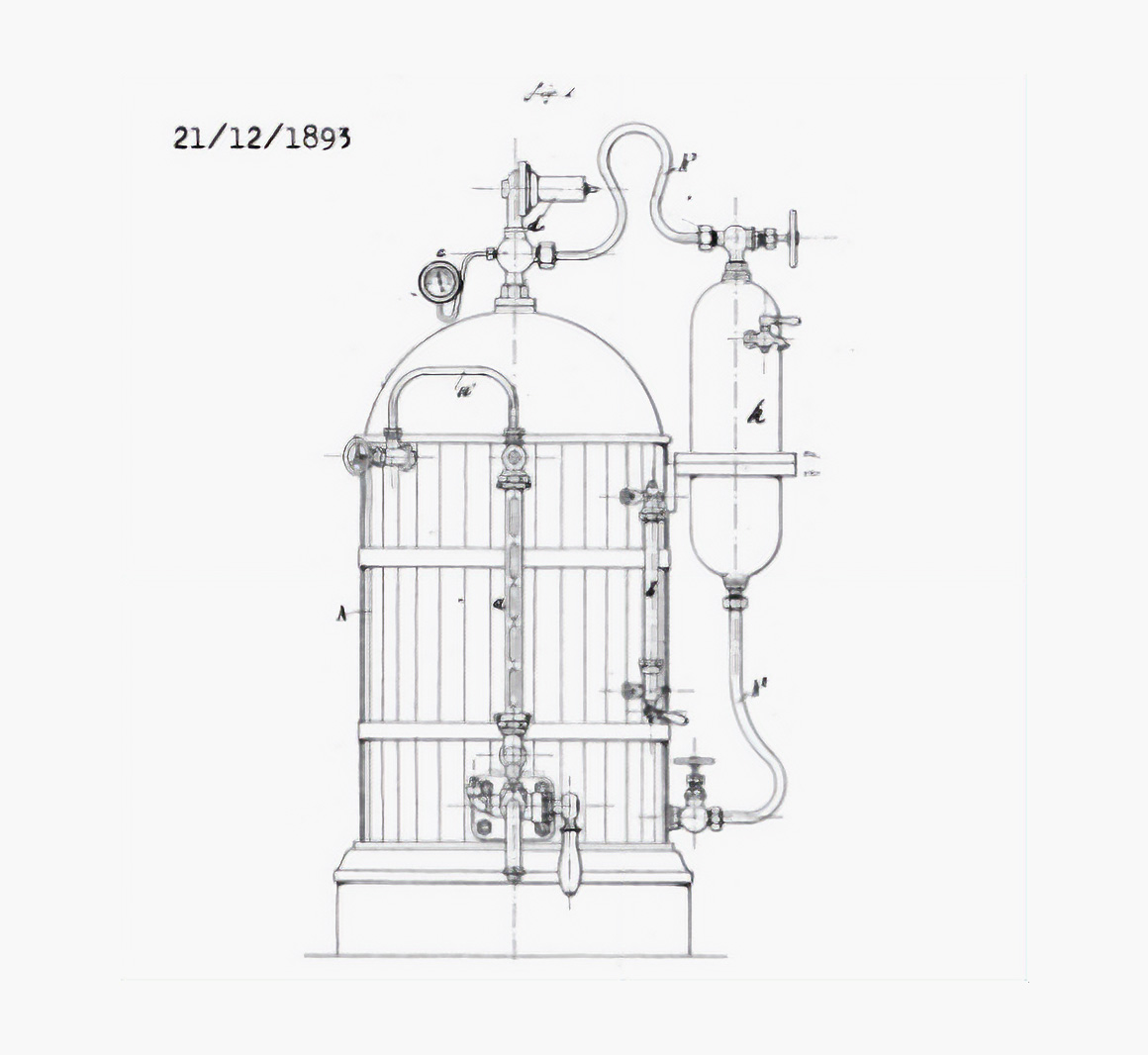

I had a lot of information but still no clear representation of his machine, apart from the technical patent drawings. But research is made of progressive steps that ultimately ‘crescendo’, and my patient quest for the first espresso machine led me to other discoveries. As I was researching the birth of espresso in Spain, I found a clear milestone out of the Spanish archive: a 1893 patent holding the same title as Angelo Moriondo’s (but in Spanish and presented by a certain José Molinari from Barcelona). When I received it for free from the archive people in Madrid, I instantly understood that it was from Moriondo and that it represents the missing link between his 1884 and 1910 patents.

Even if I couldn’t establish a clear connection between the two characters (Molinari and Moriondo), the patent drawings spoke for themselves: the drawing style, the content, and the numbering were exactly the same as in the other Moriondo patents. It was the proof that, first, Angelo Moriondo was constantly improving the machine’s technology over the years and, second, he tried to spread its technology abroad, with international patents lodged in France and then in Spain. Molinari, in that story, was certainly an Italian immigrant (a member of an historical Italian coffee roaster family in Modena) who was Moriondo’s delegate for Spain … rather than a crook who tried to steal Moriondo’s invention.3

Another interesting point about this document is that, contrary to other Moriondo patents, it shows an illustration of the machine, with a sophisticated design and a boiler covered with wood. That crucial bit of information led me to other great findings.

Original drawings from José Molinari’s 1893 patent.

Original drawings from José Molinari’s 1893 patent.

Apart from this Spanish patent drawing, no other known illustration of Angelo Moriondo’s espresso machine existed — until I found one at an auction site later that year. This illustration appeared on a 1915 bill from Moriondo’s coffee roasting company, a business that he ran with great success across the Piemontese region at the end of his life.

That illustration was very similar to the Molinari patent but without the external reservoir, hence more in line with the 1910 patent. It confirmed that different Moriondo machines existed and that from 1894 to 1914 these models certainly had a wood-barrel style. (A reference to his vermouth production activity, maybe?)

Advertising postcard from Angelo Moriondo’s coffee roasting company [S. Delprat Private collection, CC BY-SA] .

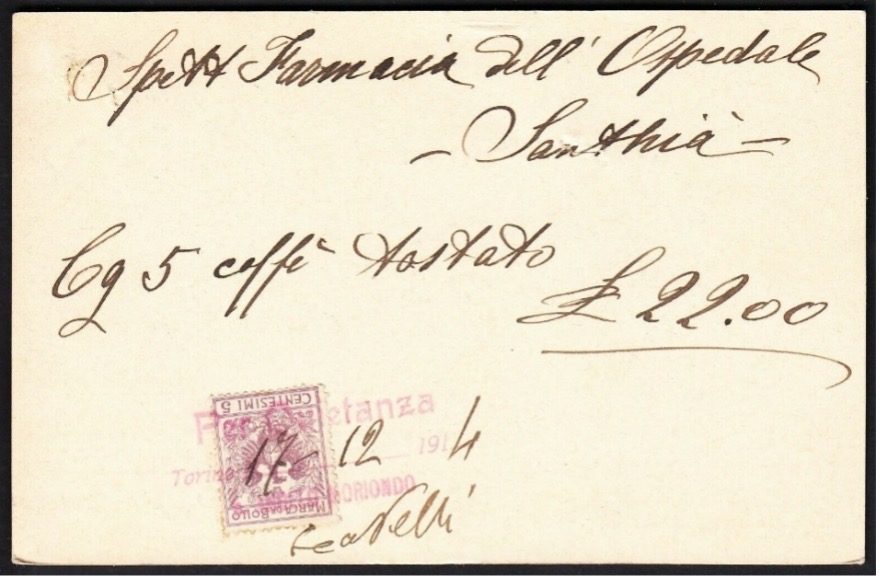

I recently found the same illustration on a promotional card from Moriondo’s coffee roasting company, dated December 1914. (Anecdotally, that card was addressed to the hospital pharmacy in Santhià, a small town between Milan and Turin … leaving doubts as to whether coffee was used as a beverage or a medicine there.)

That card advertises the electro-mechanic roaster system used (called Tornado) and the quality of its coffee, which was directly imported from the San Paolo State in Brazil (with which Angelo Moriondo had an exclusive agreement). More importantly, it advertises the ‘Brasiliana’ coffee machine model that was presented at the Brazilian pavilion of the 1911 International Exposition of Turin. Below the illustration, the caption gives some machine specifications and ends with the sentence ‘Catalog on request’, confirming that Angelo did not jealously keep his invention for his own ‘caffès’ but was also selling models of his famous coffee machine.

It is an important fact because different versions of the Moriondo story exist (first, that it was not certain that he ever built a machine, and then that only one model existed), but almost all of the versions suggest that he failed to spread the technology because he jealously kept his invention for himself. That myth of a selfish barista can now be debunked: This advertisement card suggests that Moriondo failed commercializing his machine on a large scale but that different models existed (apart from the ones standing at his ‘Ligure Caffè’ and ‘American bar’ in the Galleria Nazionale) and that he was indeed trying to sell machines through his coffee roasting activity. Moreover, as the patents lodged in different countries attest, he sold (at least tried to sell) machines not only in Italy but also abroad, in Barcelona and maybe France and Brazil.

The First Dose

This illustration and the connection with the Spanish patent prepared my mind for the rest of the story. With the image of a wood-covered machine in mind, I took a closer look at pictures from the ‘Fondazione Torino Musei’ that I had in my archive for a long time … and I saw it. It was where it was supposed to be, on the side of a display of large machines filling the ‘Galleria del Lavoro’ during the Esposizione Nazionale di Torino in 1898: the very first photographic image of a Moriondo machine.

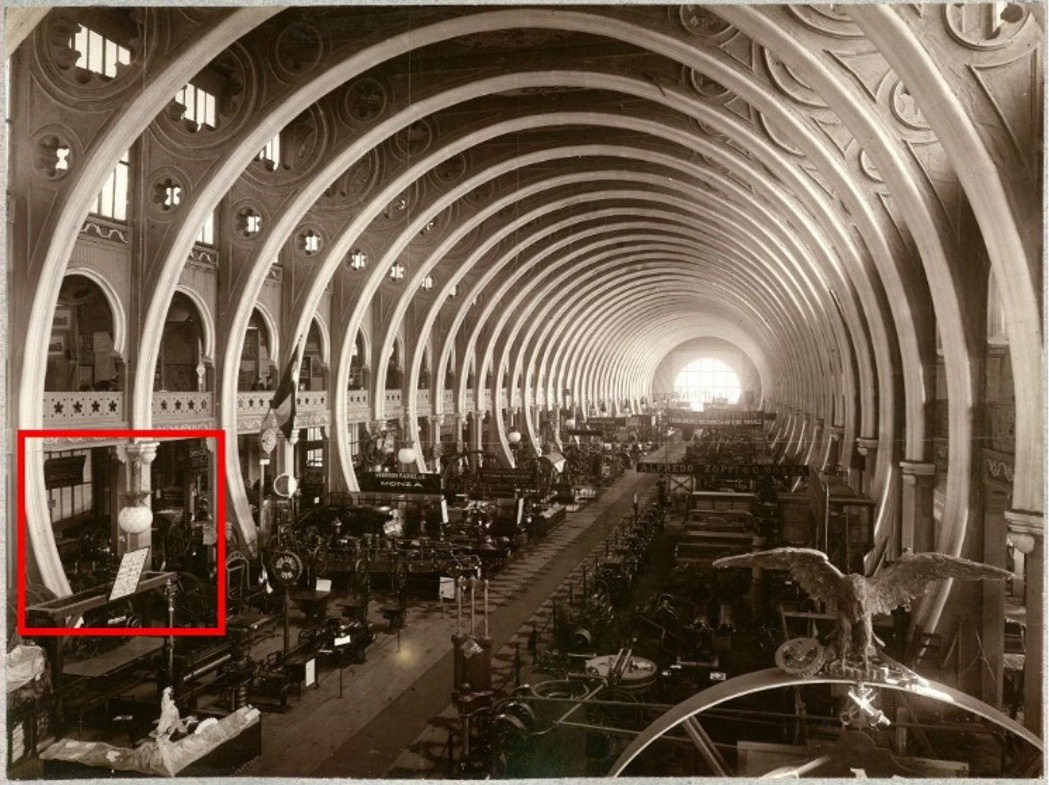

Picture of the Galleria del Lavoro at the 1898 ‘Esposizione Generale Italiana of Turin’. The red square indicates the location of Moriondo’s stand at the exhibition.4

Picture of the Galleria del Lavoro at the 1898 ‘Esposizione Generale Italiana of Turin’. The red square indicates the location of Moriondo’s stand at the exhibition.4

A detail on a small corner of an extraordinary picture finally makes it real: a Moriondo model with the outside reservoir and the wood covering, corresponding exactly to the Molinari patent published around the same years … plus a smaller model in shiny metal (closer to the very first Moriondo machines).5

As for the Moriondo coffee roasting business relics I found, I had the ‘chance’ to bump recently into another picture of the 1898 ‘Galleria del Lavoro’, taken from another angle and again showing Moriondo’s stand at the exhibition. I asked the Fondazione Torino Musei for a better-resolution picture, and here it is:

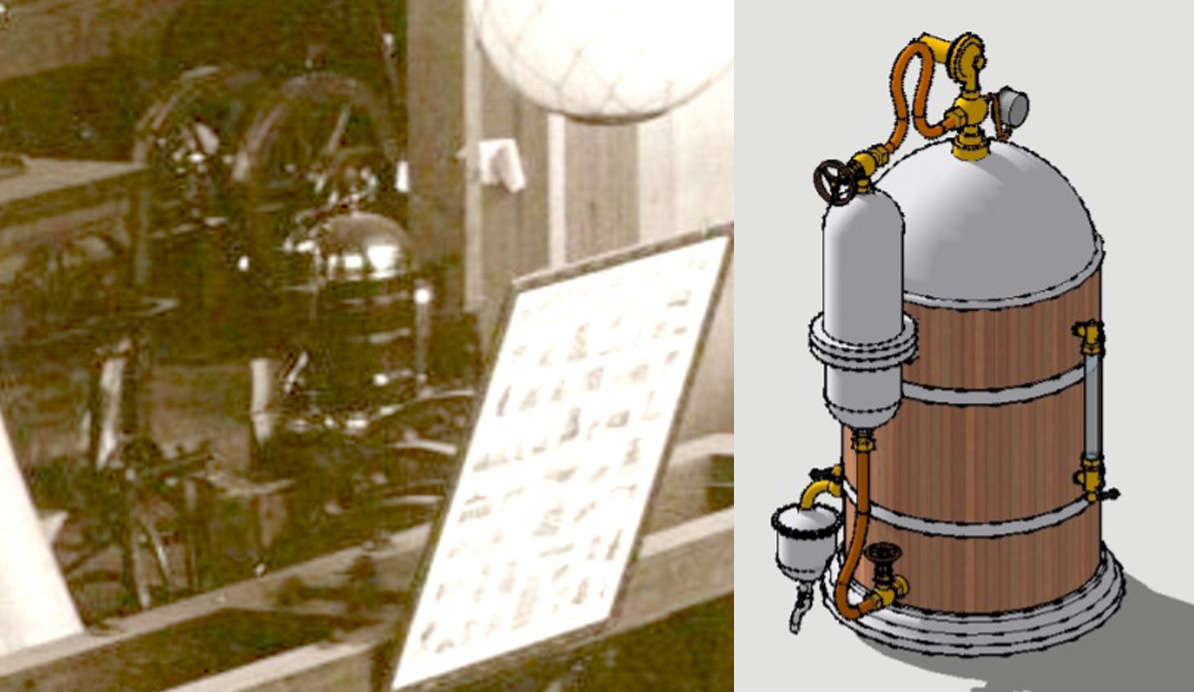

Detailed representation of the above picture (right) compared with Moriondo’s 1893 coffee machine 3D model (left).

Detailed representation of the above picture (right) compared with Moriondo’s 1893 coffee machine 3D model (left).

For the second time, the historical picture and the 3D model of Moriondo’s machine (faithfully reproduced from the Molinari patent drawings) match very well … just in case some people still had doubts about the claim.

Now, and until someone finds a picture of his first model at the 1884 exhibition, I don’t know which one is the very first picture of the Moriondo machine. But does it really matter ?

The Booster Shot

I remember precisely how I felt when I saw a picture of that machine for the first time — that incomparable feeling of finding a treasure. I must say that when I confirmed it with a second photo of more or less the same kind, the excitement was not the same. But I had the chance to feel it again … with another picture, a postcard that I wouldn’t have identified properly without the previous finds. Once again, my mind was prepared to get that chance.

A few months ago, as I was surfing on an auction site, a thumbnail image caught my eye. I couldn’t believe it: It was an early 1900s postcard with an exceptional picture of a Moriondo machine. That item had been for sale for nearly a year! I didn’t think twice or argue on the price, I just bought it and prayed that it would travel safely from Italy.

Advertising postcard from Margherita pastry and Vermouth shop in Piacenza, back side [S. Delprat Private collection, CC BY-SA].

Advertising postcard from Margherita pastry and Vermouth shop in Piacenza, back side [S. Delprat Private collection, CC BY-SA].

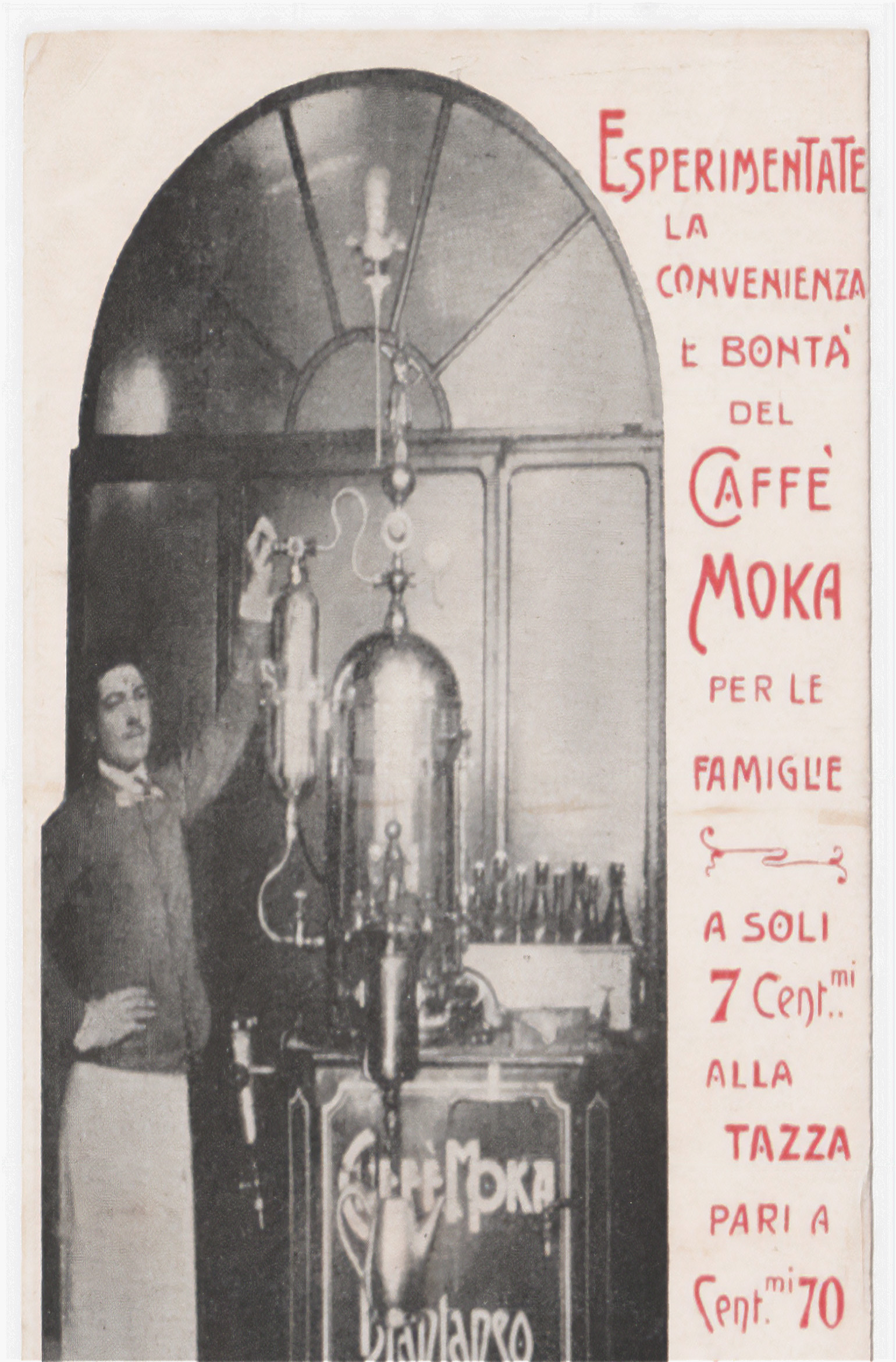

The precious advertising postcard is from a vermouth producer and pastry shop in Piacenza (a town between Milan and Parma, 200 kilometres from Torino), a business called ‘Margherita’ owned by Adamo Grandi, according to the back side of the card. It contains no handwriting or stamp, but it recalls a ‘Gran Prix’ received for their Vermouth brand at different commercial fairs in 1902 and 1903, hence establishing its date shortly after 1903.

The front side shows an early Moriondo machine model with an outside reservoir, very close to the Molinari patent but without any wood covering, making it a model dating to earlier than 1894. This confirms that multiple Moriondo machine models existed, in different places, well before 1900. On top of that, the machine has a decorative figure (looking like a Juno or Minerva goddess) on the boiler’s summit, suggesting that Moriondo also created what became a common attribute of espresso machines for the rest of the century. Wow, it’s like he invented everything at the same time.

Beside the shiny model stands a handsome man sporting a thin mustache, a dark jacket, and a waiter’s apron, operating the machine to produce coffee by the cup (for 7 cents) or by the liter (for 70 cents), as the text reads. Hence, this picture presents not only the best picture of a Moriondo machine so far but also the very first picture of a barista, before the word even existed.

Front side of the same postcard, showing a Moriondo espresso machine model in use [S. Delprat Private collection, CC BY-SA].

Front side of the same postcard, showing a Moriondo espresso machine model in use [S. Delprat Private collection, CC BY-SA].

The photo seems to show the inside of the pastry shop, where the machine sits on a trolley advertising ‘Moka Caffè – Istantaneo’, with vermouth bottles (or are these 1-litre coffee bottles?) at the back. Moriondo called his new beverage istantaneo at that time, before Pavoni popularized the word espresso. ‘Istantaneo’ was a poor choice of word, since it also designated coffee extracts (as in ‘instant coffee’ today). Surely, changing that word is part of Pavoni’s marketing genius and success in commercialising the same invention.

The card reminded me that Luigi Bezzera was also a vermouth producer and a bartender. This is certainly how he first crossed paths with Moriondo’s revolutionary coffee machine. His company, together with La Pavoni, still claim today that their 1901 espresso machine was the first one. Obviously, this is not the case: Luigi Bezzera simply filed a patent immediately after Moriondo’s first patent’s expired, using almost the same title, and during a period of time when Moriondo was still active (a fact that he couldn’t ignore).6

The key to Bezzera’s success was his partnership with Desiderio Pavoni, who was a great businessman from Milan (an owner of cinemas and cafés, who was financially able to launch a large-scale production). What we owe Bezzera is certainly the portafilter as we know it today and, for Pavoni, the successful spread of the technology around the world. That was something Angelo Moriondo failed to achieve but was trying to do towards the end of his life. All the other inventions, even the shape and style of the machine that was intended to take a place of pride on top of a bar counter, are from Moriondo.

Angelo Moriondo is the person who ignited the coffee world in 1884. All espresso lovers should pay credit to him … and to Antonio Cremonese (but that’s another story). Even Bezzera and La Pavoni will be forced to confess it at some point; let’s give them the chance. It will happen only if a sufficient number of people prepare their minds to it, and favour that field of observation.

About the Author

Sébastien Delprat is a French/Canadian research engineer who holds a PhD in physics. About ten years ago he became interested in espresso and coffee machine technology and began extensive research on the subject. Based on patents and historical archive documents, he has written many articles about the evolution of coffee makers from the French Revolution up until the 1960s.

Delprat calls himself a ‘baristorian’ and is known in the coffee community under the alias ‘Dottore Pootoogoo‘.

___

1 Originally stated in 1854 as ‘Dans les champs de l’observation le hasard ne favorise que les esprits préparés.’ 2 I published this work on a French blog called Cafeo(b)logue under the section ‘Ascenseur pour l’expresso’ (‘Elevator to espresso’), a saga that retraces the coffee machine history from the French Revolution up to the 1960s. Episode 9 و Episode 10 are dedicated to Moriondo. 3 See ‘Ascenseur pour l’expresso’, Episode 11, for more details. 4 Mario Gabinio, Torino, Esposizione Generale Italiana del 1898, Galleria del Lavoro (interno, veduta generale, stampa alla celloidina, mm 171 x 228, inv. A19/72). With the kind authorization of Fondazione Torino Musei (Archivio Fotografico dei Musei Civici, Turin). 5 This discovery is the subject of my article ‘In search of Moriondo’s espresso machine — Finding a needle in a haystack’, published in 2018 on Home-Barista (Part 1/3, Part 2/3، و Part 3/3). 6 Moriondo’s international patent, valid for fifteen years, expired on October 23, 1900. Luigi Bezzera lodged his own patent, ‘Innovazioni negli apparecchi per preparare e servire istantaneamente il caffè in bevanda’, in Italy on November 19, 1901.

0 تعليق