A countercurrent by Steam with Etzensberger by Sebastien Delprat

‘The Tour up the Nile has become so popular that very soon no American out on a “European Tour” will dare to return home and face his friends if he has not done the Orient.’ — Robert Etzensberger, Up the Nile by Steam (1872).

Covers of the Thomas Cook & Son magazine Cook’s Excursionist and International Tourist Advertiser (1861–1902) and Jules Verne’s novel Le Tout du Monde en 80 Jours (1872)

Covers of the Thomas Cook & Son magazine Cook’s Excursionist and International Tourist Advertiser (1861–1902) and Jules Verne’s novel Le Tout du Monde en 80 Jours (1872)

Towards evening, I see the high column of the Moka lighthouse rising on the horizon; then, the strip of sand which serves as its base appears right after. Behind it, the city of Moka, a mass of white houses from which rise delicate minarets. … Moka! Glorious name of which one honors the coffee as a title of nobility, I see at last this imposing city.14 — Henry de Monfreid, Les Secrets de la Mer Rouge (1931)

Whereas coffee was reserved for the elite when it reached the European continent in the seventeenth century, it slowly extended to the whole population as empires stole the precious bean of the Ottomans and began to cultivate it in their colonies during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.15 At that period, and maybe to hide behind a smoke screen the horrors of slavery used for its production, coffee brought, along with its aroma, the dreams of the Middle East, demonstrated by important inputs such as the Orientalism movement and the tremendous success of the book Arabian Nights.16

In Germany, coffee was kept away from the common people until the beginning of the nineteenth century, not only because it was in competition with beer (as mentioned in a 1777 manifest from King Frederick) but also because it represented large capital flight to foreign countries. Did this persecution of coffee drinkers perhaps stimulate their inventiveness? One can believe so when looking at the number of German (or Prussian) precursors in the history of coffee makers. These include not only Römershausen in the 1820s, but also Johann Nörrenberg, who invented the الفراغ pressure pot in 1827, and Hermann Eicke and Emil Wiesert (both from Berlin). Eicke built a precursor to the home espresso machine in 1878, and Wiesert introduced the moka pot in 1879. With regard to the espresso machine, the two inventors who can be regarded as Moriondo precursors are also of German origin.

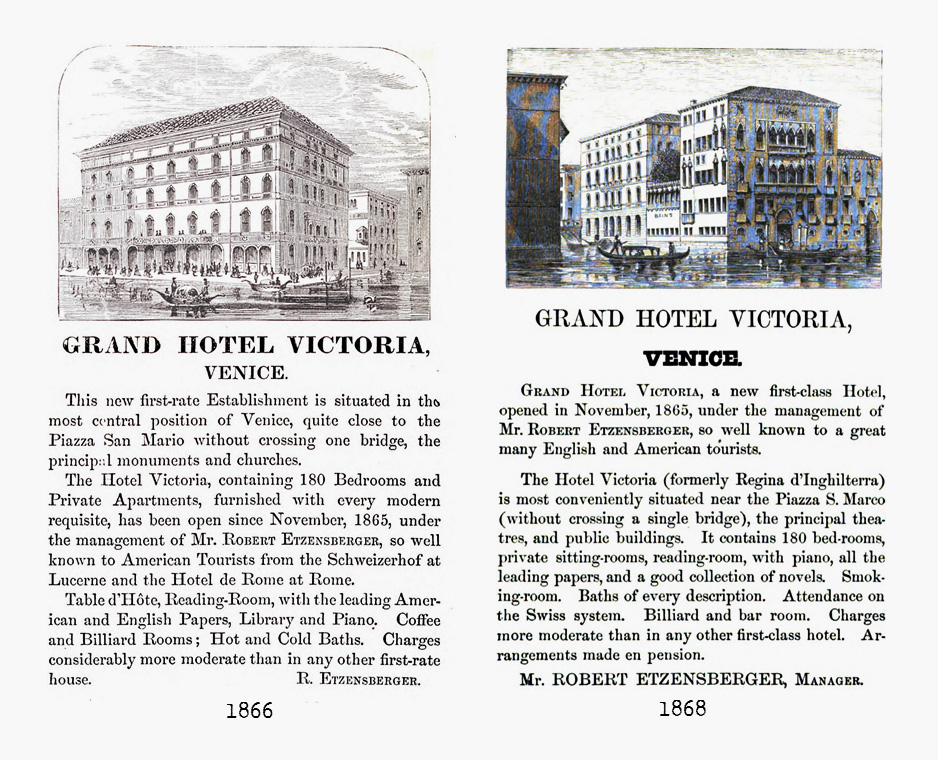

Well, to be more precise (and respectful to Swiss people), the first of the two inventors was born in Zurich. George Augustus Sala, the truculent English journalist who knew him personally, described him as ‘a highly intelligent German-Swiss’. But Robert Ulrich Etzensberger didn’t really care about frontiers, since he was regularly travelling across Europe due for work. Mentioned by the 1878 American Travellers’ Guides as having ‘one of the best reputations in Europe as director’, Etzensberger was the manager of the Schweizerhof Hotel in Lucerne and the Hotel de Rome in Rome before becoming, in 1865, the manager of the prestigious Grand Hotel Victoria of Venice. Venice was then part of the Lombardo-Venetian Kingdom, but it soon transferred from the Austrian Empire to France and was handed over to Italy at the end of 1866.

Advertisements for the Grand Hotel Victoria in Venice from Harper’s Hand-book for Travelers in Europe and the East (1866) and The American Travellers’ Guides (1868)

Advertisements for the Grand Hotel Victoria in Venice from Harper’s Hand-book for Travelers in Europe and the East (1866) and The American Travellers’ Guides (1868)

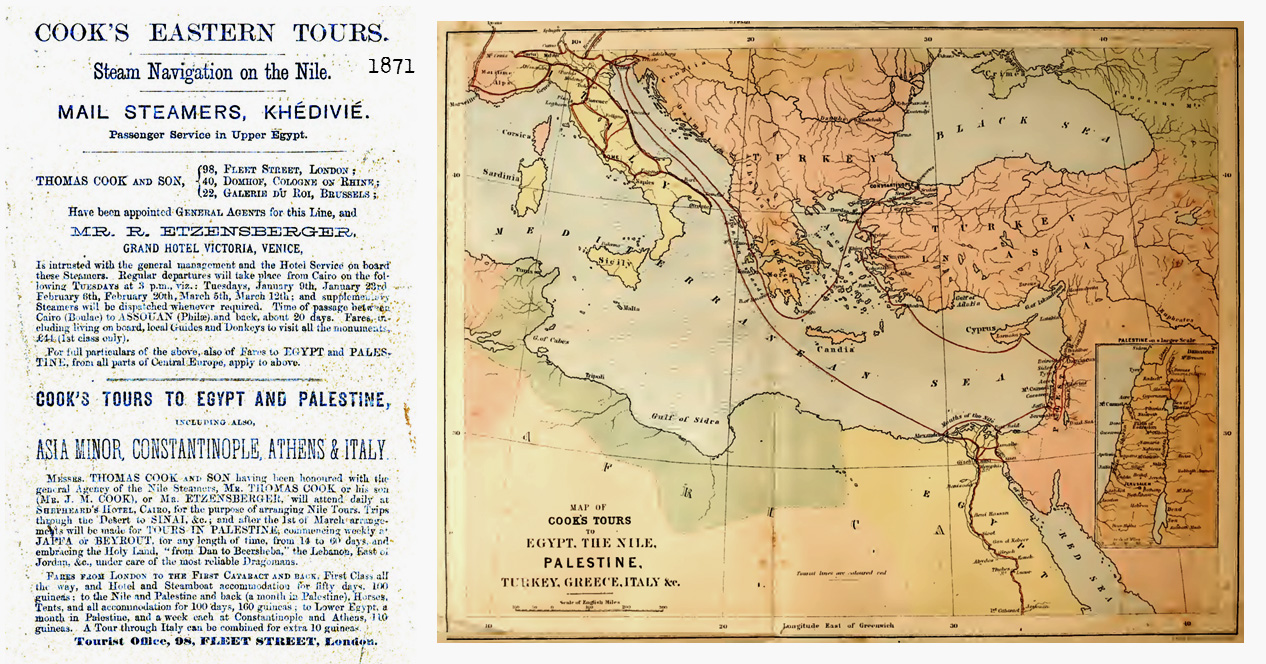

Etzensberger was also presented as a linguist, speaking ‘English, French, Italian and German with almost equal fluency’. He was one of the talented characters of the new business of guided tours and travel agencies. He made his reputation when he was part of Thomas Cook’s tour business in Europe, with his Venice hotel. As he was waiting for a new position to begin in England, Etzensberger became (in 1871) part of the first Thomas Cook travel service to Egypt. The newly built Suez Canal had opened Egypt to Europeans at the end of 1869. Etzensberger was named general agent for the commissariat of the Nile steamers and took care of the first tours to Egypt and Palestine for the Thomas Cook and Son Company in 1871 and 1872.

An extract from ‘Winter Series of Programmes of Circular, Single, & Through Tickets from London to France, Belgium, Holland, Germany, etc.’ (1871) and a map from Up the Nile by Steam (1872)

An extract from ‘Winter Series of Programmes of Circular, Single, & Through Tickets from London to France, Belgium, Holland, Germany, etc.’ (1871) and a map from Up the Nile by Steam (1872)

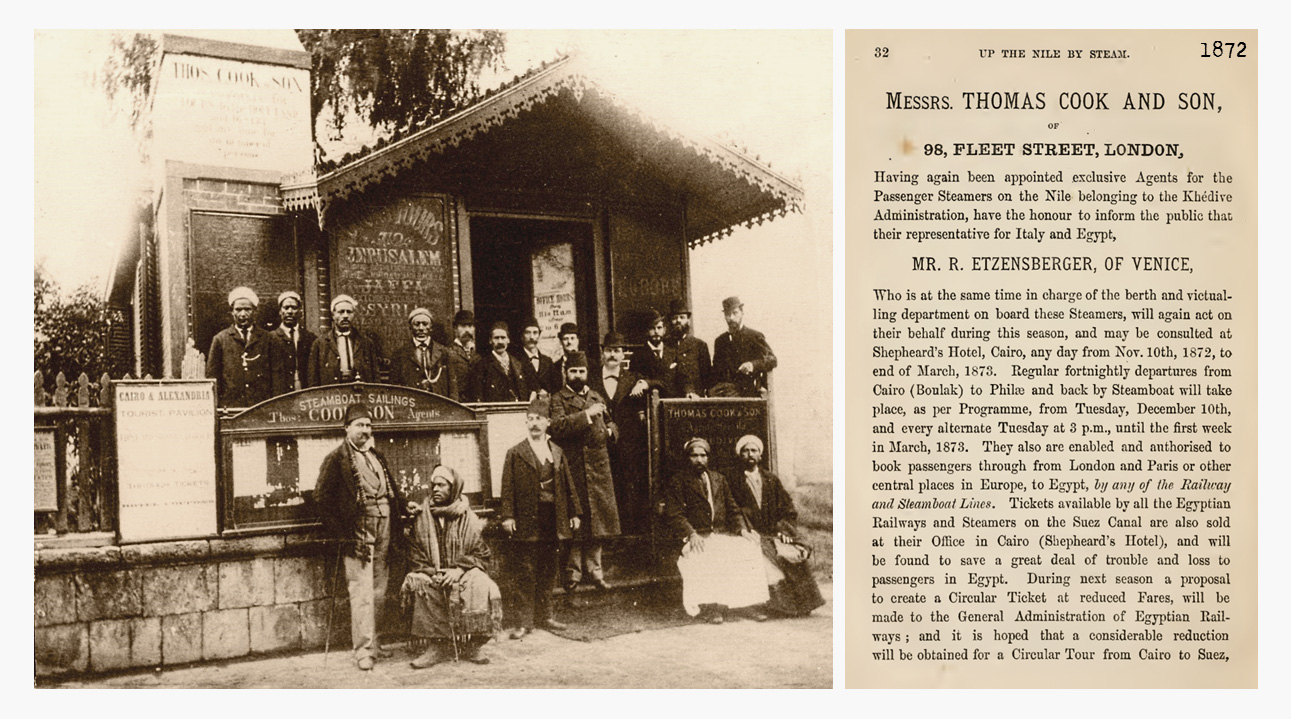

The first Thomas Cook & Son travel agency in Cairo (1870s) and an extract from Up the Nile by Steam (1872)

The first Thomas Cook & Son travel agency in Cairo (1870s) and an extract from Up the Nile by Steam (1872)

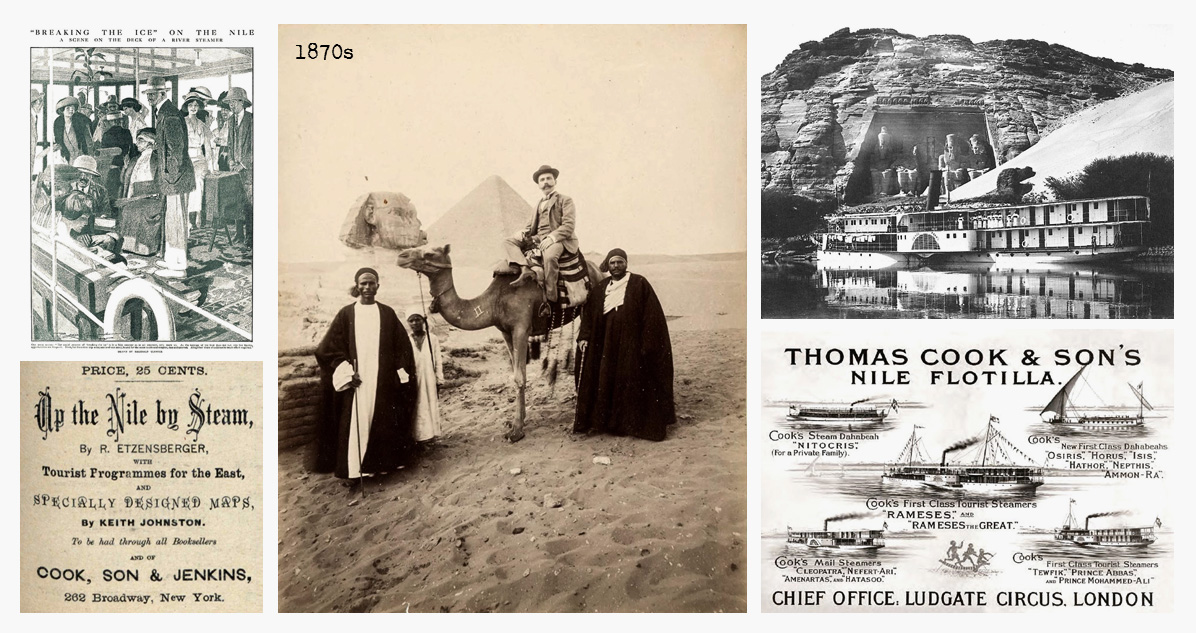

Advertising elements linked to Thomas Cook & Son’s steamer excursions on the Nile, and a typical photo taken in front of the Sphinx and the pyramids by the Zangaki brothers in the 1870s17

Advertising elements linked to Thomas Cook & Son’s steamer excursions on the Nile, and a typical photo taken in front of the Sphinx and the pyramids by the Zangaki brothers in the 1870s17

He supervised the hosting of the first tourists in Cairo at the Shepheard Hotel, and all the arrangements and catering for the steamers’ travel to Egypt’s wonders. The book he wrote in 1872 (Up the Nile by Steam) mentions that, onboard, ‘Coffee prepared in the Turkish fashion is served after all meals, and this delicious beverage can be had everywhere and at any time.’

Was it these travels to the original lands and cultures of coffee that influenced Etzensberger, or was it his experiences in Rome and Venice? History doesn’t tell us, but for sure, Etzensberger began to focus on coffee preparation for his hotel immediately after his experiences working for Thomas Cook & Son.. Following his final tour in Egypt, in 1872 he joined the Midland Grand Hotel in London, as a manager. Augustus Sala predicted that the hotel, owned by the Midland Railway and located at the St Pancras railway station in London, was ‘destined to be one of the most prosperous, as it is certainly the most sumptuous and the best conducted hotel in the Empire’. Despite some financial difficulties, Etzensberger insisted that the construction should follow George Gilbert Scott’s design, and on May 5, 1873, the hotel welcomed its first guests. At its opening, the Grand Midland Hotel was the largest in the United Kingdom, with a 600-guest capacity and splendid interiors.

Advertisements for the Midland Grand Hotel, from Bradshaw’s Notes for Travellers in Tyrol and Vorarlberg, Vol. 21 (1873) and Cook’s Tourist’s Handbook for Switzerland (1884)

Advertisements for the Midland Grand Hotel, from Bradshaw’s Notes for Travellers in Tyrol and Vorarlberg, Vol. 21 (1873) and Cook’s Tourist’s Handbook for Switzerland (1884)

In 1873, Etzensberger applied for his first patent. True, England was not the land of coffee, but he came from a different country, and he had a deep knowledge of cultural experiences. He wanted to serve his hotel customers the best cup of coffee in the Empire. His patents, filed in the UK and the US from 1873 to 1880, reflect his continuous efforts to develop a coffee machine capable of producing coffee for either a hotel or a home, and it included a practical way to recharge coffee. The ‘box’ for coffee (or tea) was positioned on top of the machine or mounted on a tap, making it easy to remove the spent grounds or tea leaves.

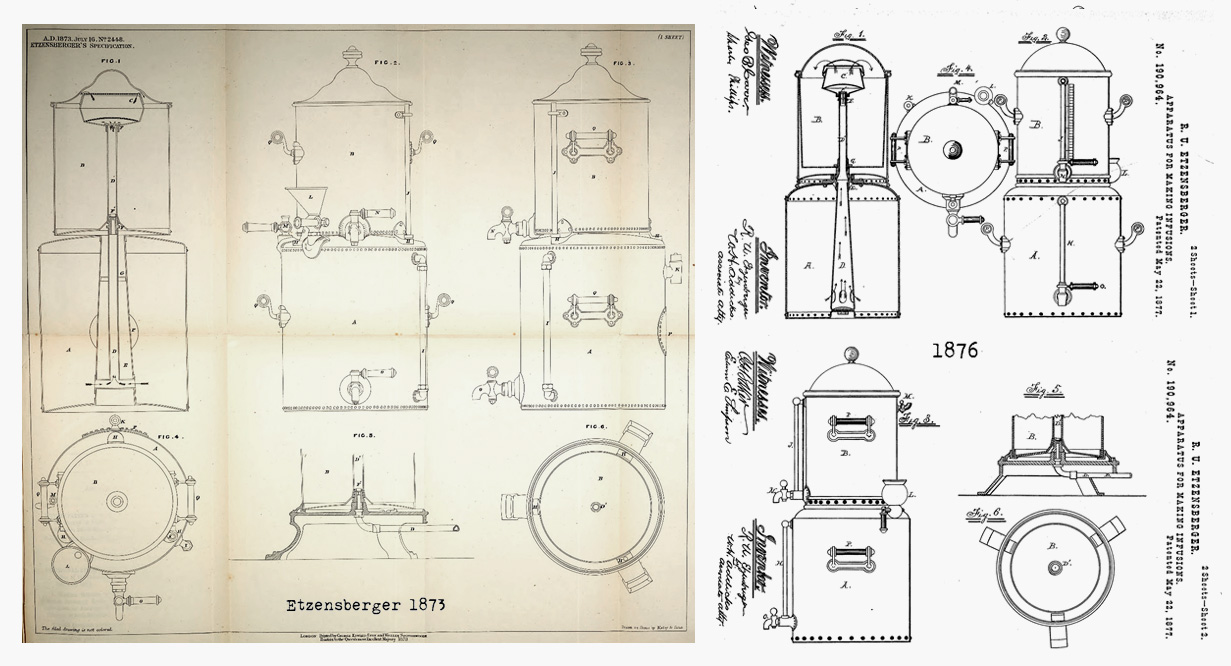

British (1873) and US (1876) patents from Robert Ulrich Etzensberger show his first coffee machine, which worked on the principle of steam pressure, featured a coffee strainer located on the machine’s top, and was easily rechargeable.

British (1873) and US (1876) patents from Robert Ulrich Etzensberger show his first coffee machine, which worked on the principle of steam pressure, featured a coffee strainer located on the machine’s top, and was easily rechargeable.

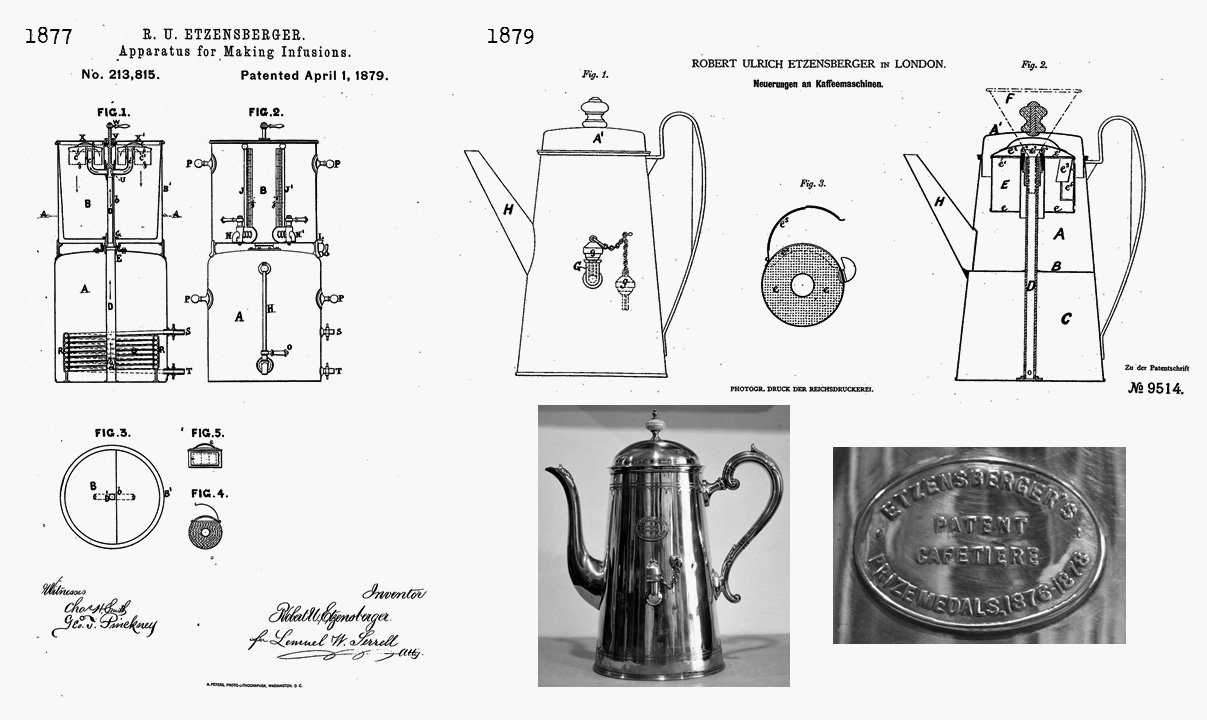

Left: Etzensberger’s US patent, from 1877, for a two-side machine (one for coffee, one for tea) works on the same principle as his previous patents. Right: development of the ‘coffee box’ idea was also applied to a home coffee maker, as shown in a German patent from 1879 and a luxurious model that survived time.

Left: Etzensberger’s US patent, from 1877, for a two-side machine (one for coffee, one for tea) works on the same principle as his previous patents. Right: development of the ‘coffee box’ idea was also applied to a home coffee maker, as shown in a German patent from 1879 and a luxurious model that survived time.

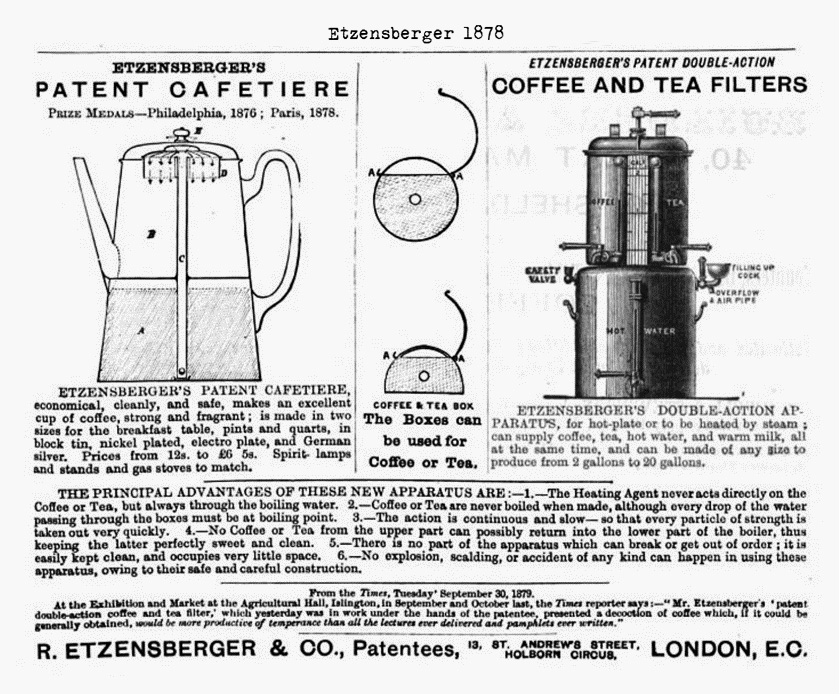

An advertisement for Etzensberger’s products in The Coffee Public-House News (same two models as the ones presented in the patents, on previous illustration), 1878

An advertisement for Etzensberger’s products in The Coffee Public-House News (same two models as the ones presented in the patents, on previous illustration), 1878

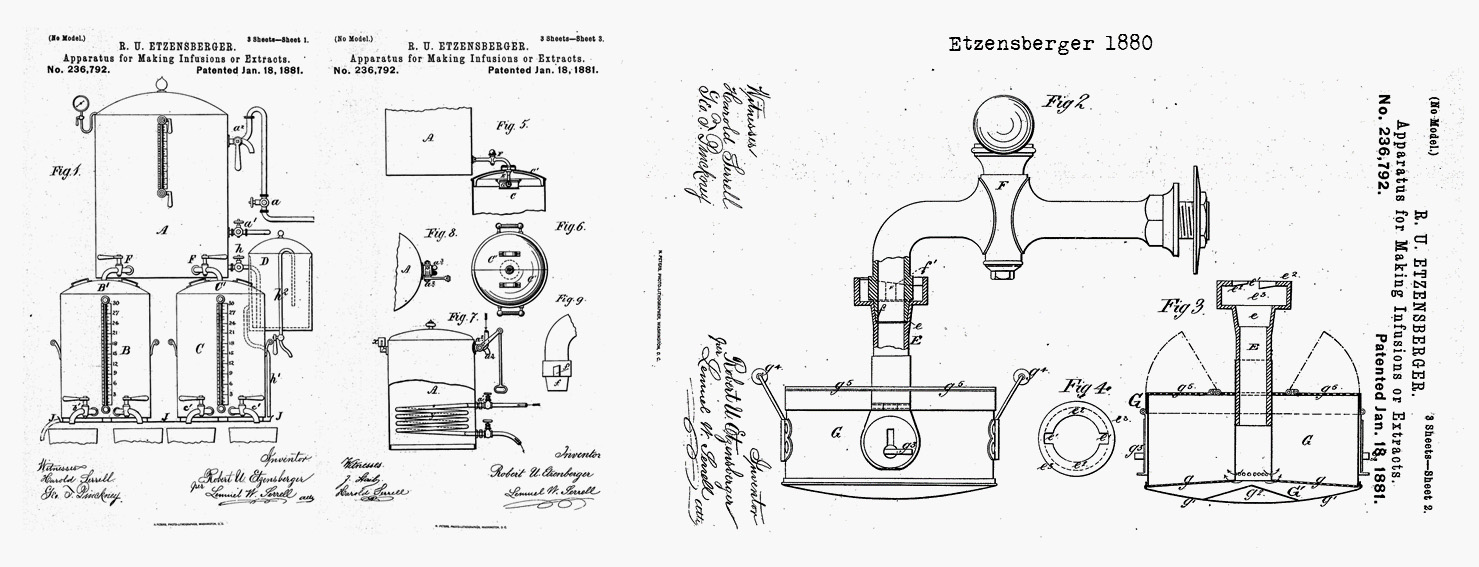

The last patent from Robert Ezensberger (from the US, 1880) shows his ‘coffee box’ attached to the steam-pressured water tap by a special fitting, making it a precursor system to the espresso machine portafilter.

The last patent from Robert Ezensberger (from the US, 1880) shows his ‘coffee box’ attached to the steam-pressured water tap by a special fitting, making it a precursor system to the espresso machine portafilter.

Anyone looking at its 1880 patent, which shows a coffee box screwed onto a tap and uses steam force to pass hot water through the ground coffee, should be reminded of Moriondo’s first coffee machine model. The way the boiler was built — with a tall, vertical orientation — is also notable. The coffee box was located in a closed container, and the whole apparatus was intended to produce large quantities of coffee. This design was a clear step toward the removable portafilter.

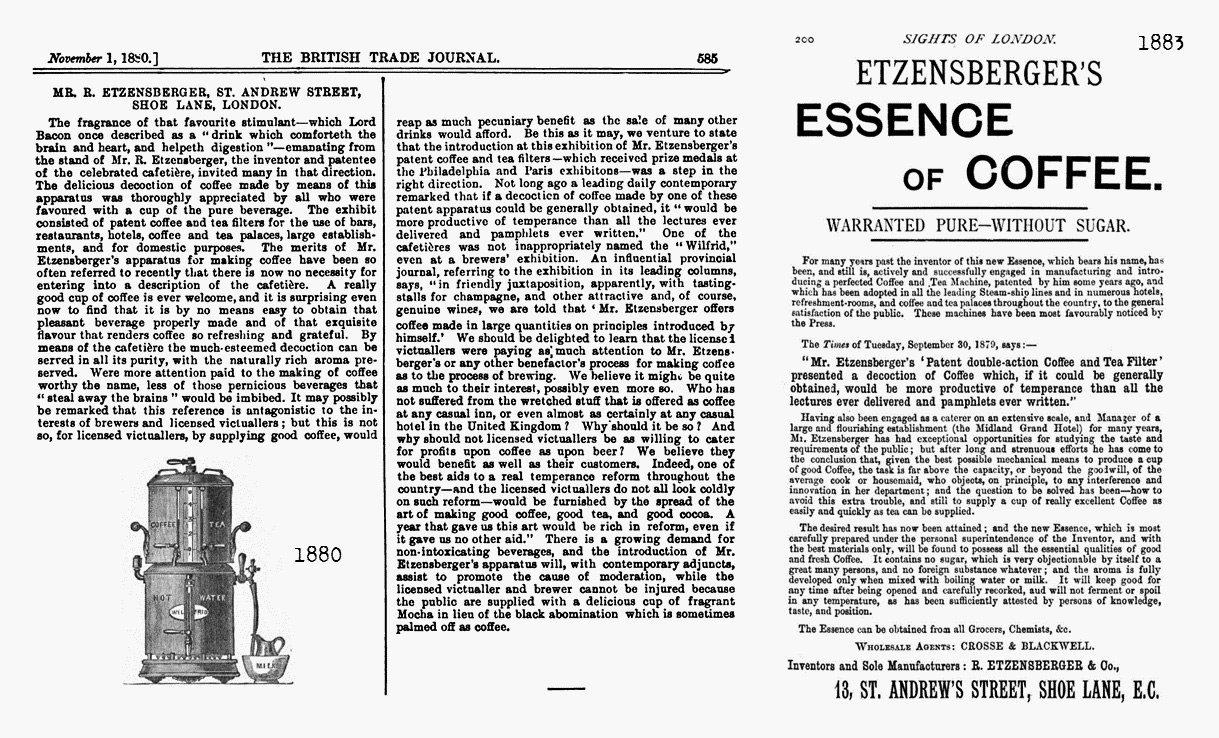

Etzensberger’s coffee machines were produced in large numbers, advertised in many journals, and promoted by Thomas Cook & Son magazines, as did his friend George Augustus Sala in his journals. These machines equipped hotels, coffee houses and steamships. Etzensberger’s coffee machine models were shown at the Paris and Philadelphia exhibitions.

Extracts from The British Trade Journal (1880) and Sights of London (1883)

Extracts from The British Trade Journal (1880) and Sights of London (1883)

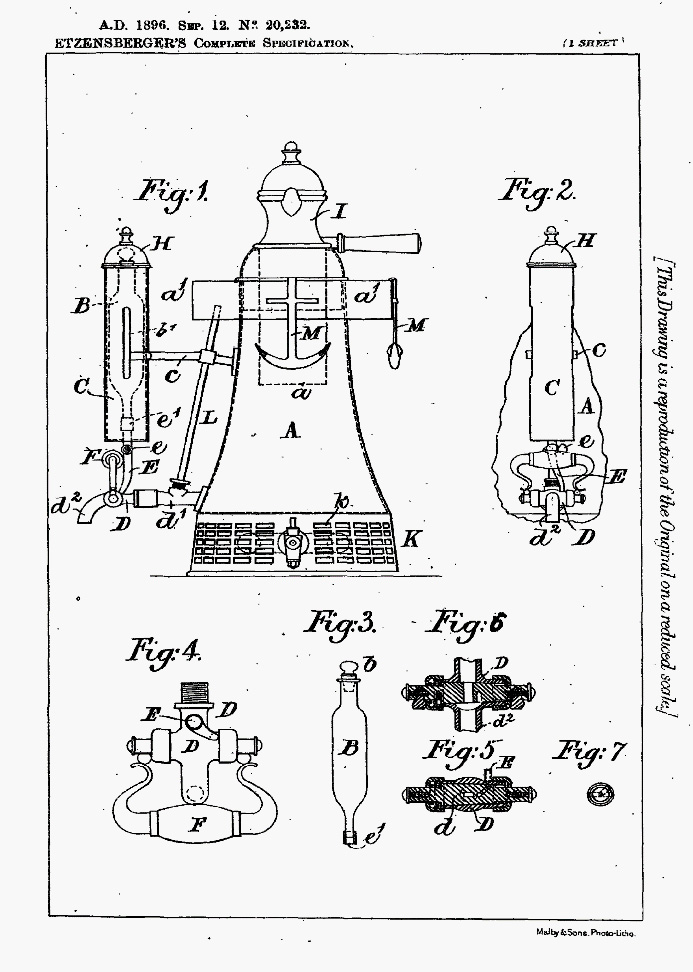

It seems that his own son pursued his passion for coffee machines. An inventor named Albert Etzensberger from London filed a patent in 1896 for a coffee urn designed to serve coffee made out of coffee extracts. It was certainly the same coffee extract that E. Etzensberger and Co. was selling under the name ‘Etzensberger’s Essence of Coffee’.

Drawings from Albert Etzensberger’s 1896 patent, titled ‘Improvement in Urns Suitable for Retaining Hot Coffee and Milk, or Other Hot Beverages’

Drawings from Albert Etzensberger’s 1896 patent, titled ‘Improvement in Urns Suitable for Retaining Hot Coffee and Milk, or Other Hot Beverages’

A striking point about Etzensberger and Moriondo is their common background: both were managers of grand hotels in an important city, located next to main train stations. It is highly probable that these two passionates of coffee machines met at some point, or at least that some clients of their respective hotels mentioned one to the other. It’s impossible to say for sure, but in the moving world that was the end of the nineteenth century, large cities such as London and Turin were better connected than ever before.

14 The original text reads, ‘Vers le soir, je vois se dresser sur l’horizon la haute colonne du phare de Moka ; puis, la bande de sable qui lui sert de base apparaît à son tour. En arrière, la ville de Moka, masse de maisons blanches d’où s’élancent des minarets délicats. … Moka! Nom glorieux dont on honore le café comme d’un titre de noblesse, je la vois donc cette ville imposante.’

15 Check the map of the historic distribution of Coffea arabica prepared by the Specialty Coffee Association of America.

16 First translated in Europe as Les Mille et Une Nuits by the same Antoine Galland who wrote De l’Origine et du Progrès du Café

17 Since the person sitting on the camel appears to be the same as the one standing on the stairs of the first Thomas Cook agency in Cairo, I like to imagine that this character is Etzensberger himself … who knows?

0 تعليق