by Lucia Solis

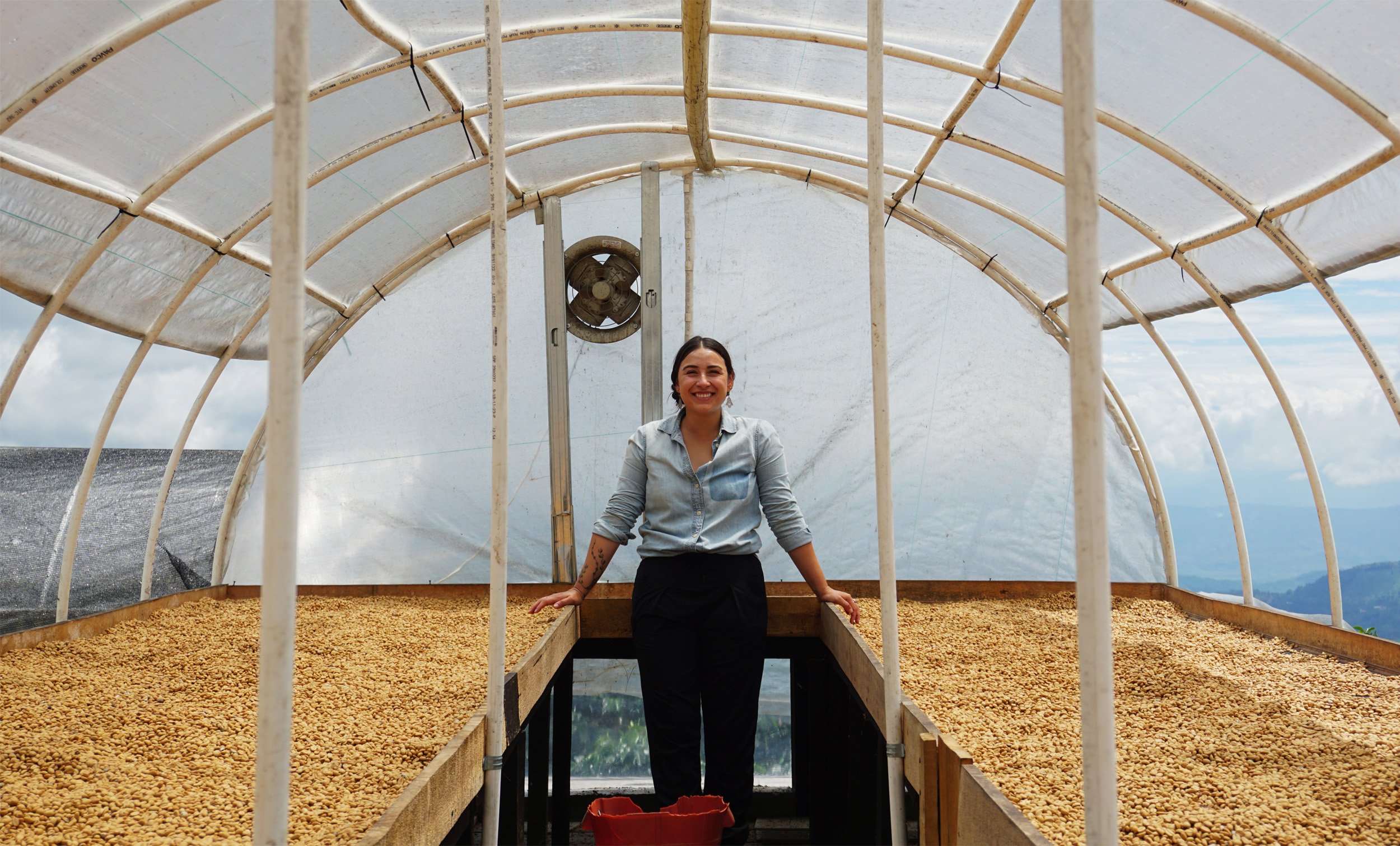

Parchment drying in a parabolic tunnel, Risaralda,Colombia January 2021.

Parchment drying in a parabolic tunnel, Risaralda,Colombia January 2021.

Several years ago I got the unfortunate nickname of Yeast Girl.

When I was studying Viticulture and Enology at UC Davis I never dreamed my microbiology path would eventually lead me away from wine and towards coffee fermentation. I had a successful career working in wine production in Napa Valley, California. When Scott Laboratories approached me in 2014 to work in coffee fermentations, I didn’t even drink coffee. At the time, Scott Laboratories hired me to explore the market for yeast and coffee application. Scott Laboratories (not to be confused with the Scott Laboratories of the Kenyan SL coffee varieties) has almost 100 years of yeast experience. They sell yeasts to wineries and breweries, and they were interested in breaking into the coffee and cacao markets.

Scott Laboratories in California was working with Lallemand in France. Lallemand is a privately held Canadian company that specializes in the development, production, and marketing of yeasts and bacteria. The laboratory in France was doing the research in small-scale, controlled experiments and I was hired to scale their findings to production levels. I traveled to 13 different coffee-producing countries to inoculate coffee fermentations with different test strains and then, eventually, commercial yeast strains.

Small scale yeast fermentations at the Lallemand Research and Development facilities in Toulouse, France October 2016

Small scale yeast fermentations at the Lallemand Research and Development facilities in Toulouse, France October 2016

Even though I parted ways with Scott Laboratories in 2016, I continue to use their strains because I have seen how versatile they are. I have seen how well they work across many different applications.

In 2018 Lallemand even won Best New Product in the open class at SCA Seattle for the Intenso yeast strain. In the last 5–7 years the specialty coffee industry has become more open to talking about fermentation as well as trying extended and inoculated fermentations. Yet it has been my experience that, despite the interest and how much more attention we pay to processing today in the specialty industry, there is still a lot of confusion around the topic for coffee producers and consumers alike.

This article is for any producer who is curious about trying yeast out or for consumers who are increasingly buying coffees that feature the word yeast on the package label.

Terminology: ‘With Yeast’ or ‘No Yeast’

Yeast rehydration in 5 gallon bucket, Kona, Hawaii 2017

Yeast rehydration in 5 gallon bucket, Kona, Hawaii 2017

My goal here is to take one narrow topic, yeast application, also called yeast inoculation, and address some common questions.

One thing I would really like to change is how we frame these fermentations. Often, the language we use can be confusing. For example, when producers use commercially available yeasts to inoculate their fermentations, the resulting product is labeled ‘With Yeast’, whereas the product produced by the standard processing method — the control batch — will be referred to as ‘No Yeast’.

And this is not correct. Yeast as a microorganism is everywhere. The main source of yeast in any given coffee fermentation is the skin of the coffee cherries. Even human skin is a source for yeast. This source of yeast can be more of a factor in Rwanda for example, where it is common for workers to enter the fermenting tanks barefoot to mix and wash the coffee.

Washing coffee after a fermentation with Angelique of Buf Coffee, Kigali, Rwanda 2018

Washing coffee after a fermentation with Angelique of Buf Coffee, Kigali, Rwanda 2018

Even if you are not intentionally adding a commercial yeast to a coffee fermentation, many varieties of yeast are already present. They come from the soil of the farm or from the cherry skin, and they can also be found in the water used for processing or on equipment such as tanks and pulpers.

When we simply use the word yeast on labels to try to differentiate the coffee batches, we aren’t saying very much. You would be hard-pressed to find a coffee that is truly without any yeast.

Instead of ‘yeast’ and ‘no yeast’ terminology, I prefer to differentiate the batches of coffee as wild fermentations (relying on yeast and bacteria found in the environment) versus inoculated fermentations (purchased or cultivated yeast and bacteria).

I recommend avoiding talking about ‘inoculated’ versus ‘natural’/’native’ fermentations. The words natural and native are associated with moral implications that, in my opinion, don’t contribute to the scientific conversation. Most of the microbes that are found in coffee fermentations (even without commercial inoculations) are not ‘native’ because coffee plants are not native to an overwhelming number of the places they grow. To be truly accurate, you could say ‘coffee fermented with local microbes’.

Because yeasts have been part of coffee fermentations since the origins of processing, using commercial yeast strains can be seen as less of an innovative, cutting-edge strategy and more like producers finally taking their blindfolds off. Intentionally inoculating coffee fermentations allows us to begin to understand a biological process that has been happening under our noses — but without our notice.

I bring this up because a lot of the pushback against using yeast puts it into this radical category — as though yeasts are something foreign or ‘other’. But what I would like to repeat is that yeasts have been steadily fermenting our coffee since the beginning, and the radical part is that we are now noticing what’s been happening all along.

So, if you’re a coffee producer who does any kind of fermentation (natural, honey, or washed process), congratulations, you are already using yeast to ferment your coffee. If you’re a coffee consumer, you have probably already tasted a thousand cups of coffee in which yeast has played some role.

The goal with inoculation is to bring the yeast out of the shadows and into a prominent role.

What Does It Mean to Inoculate?

Okay, we’ve explained that yeasts are already part of coffee fermentations. So, how do you use yeast intentionally? How do you inoculate a fermentation?

I think the word inoculate can be intimidating. It conjures images of a sterile lab, maybe a syringe. Many people think that you might need special equipment to inoculate the tanks or to dose the yeast. Many wonder how they can replicate a lab environment in a traditional open-air, unhygienic wet mill.

Fortunately, ‘inoculate’ is a flexible concept. It can mean all the above, but it can also be very simple. I like to think of the word inoculate as ‘introduce’. Inoculation is like a friendly introduction among friends.

Can a Producer Inoculate Incorrectly?

Producers buy yeast commercially so they can introduce a specific strain of yeast to the coffee fermentation. And, like introductions in our lives, they can sometimes go great or sometimes go poorly. In other words, yes, it’s possible to inoculate incorrectly. You can introduce (inoculate) a coffee fermentation with yeast in a bad way.

For the purposes of this discussion I am not going to cover other types of inoculations such as adding fruit to a coffee tank, adding a previous fermented batch to a new batch, or adding yogurt or other starter cultures. In this article, we are focusing only on adding commercially available yeast. This means that a single population (strain) of yeast has been identified, and that population has been grown under laboratory conditions to produce a very high concentration of a single strain. And then it is dried, packaged, and sold.

Granulated dry yeast. Stockphoto

Granulated dry yeast. Stockphoto

As a coffee producer, you purchase the bag of yeast (which is in the form of a granulated powder), and the inoculation process can be as easy as opening the bag and dumping the contents into the tank.

How Much Yeast Should You Add?

The first place the process can go wrong is if you’re not paying enough attention to dosage. Each yeast manufacturer will recommend (usually printed on the bag, or found on their website) the quantity of yeast you should add per fresh weight of coffee (coffee cherries or pulped coffee).

Yendris and Lucia rehydrating yeast. Risaralda, Colombia. March 2021

Yendris and Lucia rehydrating yeast. Risaralda, Colombia. March 2021

Currently, because it’s a new product and shipping is expensive, bags of yeast are costly, and thus it’s tempting to lower the recommended dosage. But do not give in to the temptation! If you don’t pay attention to the dosage, or if you try to save money by underdosing or by trying to ‘stretch’ the bag of yeast, this will work against you.

Selected yeast (inoculated) in coffee fermentations work by outcompeting the existing microbes. Remember, the coffee cherries already harbor their own local (not native) yeasts. When you inoculate with a different selected strain of yeasts, you want to ensure that the yeasts you are introducing are going to take over. If you inoculate with a weak dose, the selected yeast won’t be able to outcompete the local microbes, and therefore it cannot dominate the fermentation.

The way I see it, trying to use less than the recommended dosage to save money is the biggest waste of money because you won’t get the desired effect.

Can You Add Too Much Yeast?

What about the opposite scenario? Can you overdose the cherries? Or should you overdose the yeast, just to be sure you’re using enough? In our culture of ‘more is more’, it’s often tempting to add more yeast to the fermentation.

Adding rehydrated yeast to fermentation tank Matapalo, Peru October 2016

Adding rehydrated yeast to fermentation tank Matapalo, Peru October 2016

Overdosing is not as much of a problem as underdosing, although it’s still not recommended. A higher dose than the one recommended will not give you a faster fermentation. It’s more likely to stress out the yeast, deplete the resources (sugar and minerals) too quickly, and potentially kill the yeast and stall your fermentation — or end it altogether.

By trying to go faster, many producers stumble and fall flat. Once you hit critical biomass, once you pass the threshold for the yeast to dominate the fermentation, adding more yeast won’t give more benefit, and you’re more likely to stress and harm the yeast. As I mentioned earlier, it’s a waste of money to dose higher.

I advise a first-time user of commercial yeast to follow the dosage instructions as closely as possible. There are many ways to be creative in coffee fermentations, but messing with the dosage is not one of them.

What Is the Role of Temperature?

We already talked about how you shouldn’t try to speed up a fermentation by overdosing with yeast — but what about controlling the temperature?

Many of us know that heat speeds up reactions. In chemistry this is true. In microbiology this statement has its limits. To a point, warming up a fermentation can increase the speed of the reactions. But if you’re not careful, you can push a microbe outside its optimal temperature range or kill it. Or you can go too cold, in which case the yeast might die or go dormant. When playing with temperature keep in mind that inoculation is not a chemical reaction with a linear relationship between heat and speed. It’s a biological reaction, and it’s nonlinear.

A common stumbling block when using commercial strains is not being aware of the temperature requirements of the yeast. For example, many producers like to use beer yeast to ferment their coffee. Many of the Latin and Asian coffee-producing countries have robust beer-drinking cultures, so beer yeasts are easier to find than wine yeasts.

Sometimes when producers use beer or wine strains, they don’t realize that those are optimized to work best at certain temperatures that are difficult to achieve in coffee. Let’s suppose you want to use your favorite lager yeast in El Salvador, where ambient temperatures during harvest can be 28℃ to 35℃. In this situation the fermentation can get into trouble when a lager yeast is used because lager yeasts are cold fermenting; their temperature range is 4℃ to 12℃. Even ale yeasts work best towards the cooler end of 13℃ to 20℃.

Many coffee fermentations that I work with are often between 21℃ to 25℃. When the temperature of the fermentation is outside of the optimum range of the yeast, at worst the yeast can die and at best they will struggle. You’re more likely to get off flavors and aromas even if you did everything right with dosing.

Should You Add Yeast to Whole Cherries or Pulped Coffee?

Should you inoculate the whole coffee cherries with yeast, or should you pulp the coffee first? This could be considered a matter of preference, but my goal when working with producers is efficiency and scalability.

The most effective way to use yeast is on pulped coffee. This is because the main sugar source for yeast is glucose. This simple sugar is found in the mucilage. If you inoculate coffee cherries with yeast, the majority of the sugar will be trapped under the skin, and the yeast can starve and die or struggle and produce off flavors. Additionally, the cherry skin is where most of the local yeast is.

So, in my experience, inoculating whole cherries is a waste of money because you are required to use a higher dosage and you’re also making the conditions difficult for your yeast by hiding their food. It’s like running a race and voluntarily starting behind everyone else.

What is the cost of inoculation?

Inoculation should be inexpensive; it should be about 3 to 5 cents per pound of dried green coffee. And yet, today it’s almost 4 times that. As I see it, the problem is mainly distribution.

Commercial yeast most commonly comes in one presentation of 500g. Depending on the brand, you can find 500g of yeast for $20 or $60. A common dose is 1g of yeast per KG of fresh weight of coffee. This means that one 500g package can be good for 1,000KG of cherry (which is roughly 500KG of pulped coffee with mucilage). This can turn into roughly 182KG of green coffee or about 2.6 sacos of coffee. This is a range between $0.05 (for the $20 bag of yeast) and $0.15 (for the $60 bag of yeast).

Receiving cherries. Risaralda, Colombia March 2021

Receiving cherries. Risaralda, Colombia March 2021

This price is purely for the cost of yeast. However, shipping costs and importation fees can almost double this figure. And each country can have different requirements of certification, which can add to the cost There can also be a long delay. Even before the current pandemic related shipping delays, I remember it could take several months from the time a producer ordered yeast for it to arrive at their mill.

A way for a producer to get this cost down is to buy yeast in bulk. Instead of buying 500g packets, buying the next size up is 10KG. This can usually reduce the cost of yeast by 30 to 40%.

Next logical step is, why does the yeast need to be imported? Why can’t it be produced in-country? Well, it just can’t. Coffee producing countries are too hot for yeast plants. The best location is Denmark. The reactions to isolate and grow yeasts are too exothermic. So it needs to be done in cold countries to take advantage of natural cooling. Scientists have still not solved this problem, so yeast cannot be produced in the countries where it is used.

About Lucia Solis

Lucia Solis is a coffee processing specialist, she specializes in “microbial demucilagination”, or the use of microbes to process coffee following pulping. Born in Guatemala and raised in San Francisco, Lucia studied Viticulture and Enology at UC Davis prior to working in Napa as an enologist. She started working with yeast and coffee fermentation in 2014.

She has a podcast focused on microbes and coffee fermentation called Making Coffee with Lucia Solis.

Website: www.luxia.coffee

0 Comments