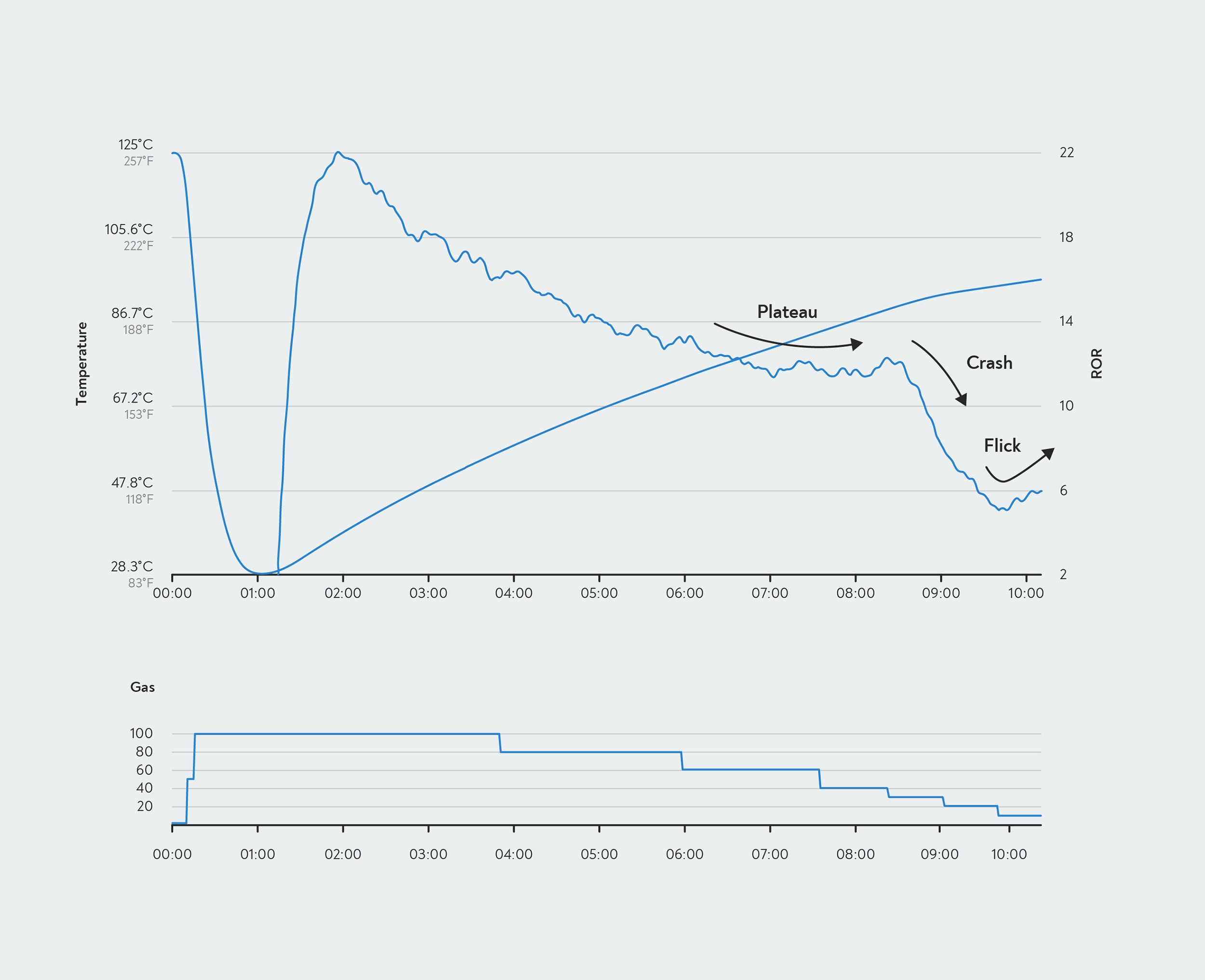

The ‘crash’ refers to the moment during first crack when the bean-temperature rate of rise (RoR) nosedives. Some beans are more prone to crashing than others, but most coffees will undergo a crash to some degree, unless you take steps to prevent it from happening.

Firstly, the RoR has a tendency to level off or even increase in the run-up to first crack. Shortly after first crack begins, the RoR suddenly drops. After the crash, towards the end of first crack, the RoR starts to recover and may ‘flick’ upwards.

This flick in the RoR invariably leads to roasty, even ashy, flavours — so much so that it is sometimes called the ‘flick of death’ because of its deadly effect on the coffee’s flavour.

The crash and flick. Before first crack, the rate of rise begins to level off. This is followed by a crash once first crack begins. At the end of the crash, the rate of rise flicks back up.

The crash and flick. Before first crack, the rate of rise begins to level off. This is followed by a crash once first crack begins. At the end of the crash, the rate of rise flicks back up.

By itself, the crash doesn’t have a severe impact on the coffee. It can make a coffee slightly less round, sweet, and juicy, but a coffee with a crash in the RoR can still taste good. The problem with the crash is what comes afterwards.

Once the coffee has crashed, you have no good options if you want to continue the roast. If you let the RoR flick back up, roasty, ashy flavours will creep in. If you drop the gas to stop the RoR from flicking back up, the RoR will flatline, which can lead to baked, roasty flavours. If you let the RoR drop further, then the roast might stall entirely. (A ‘stall’ occurs when the RoR reaches zero, so the bean temperature stops increasing and the roast stops developing the coffee.)

Faced with these choices, many roasters choose a fourth option: to drop the roast at the end of the crash, before the RoR has a chance to flatline or flick back up.