You asked us, ‘Why is it that the aroma of coffee can be so different to the aftertaste; even though presumably the same chemicals are involved?’ Here’s what we found out:

Aftertaste, in coffee, refers to the tastes and aromas left in the mouth after swallowing. Compared to other drinks, coffee flavours hang around for a long time: the aftertaste of an espresso can last up to 15 minutes (RJ Clarke and OG Vitzthum, 2001).

Depending on the coffee, this may or may not be a good thing. But no matter how good your coffee is, the aftertaste is always different (and often less pleasant) than the flavour of the brew. And a coffee that tastes perfectly fine when you drink it can leave you with a lingering ashy or metallic taste in your mouth.

So why do only some of these tastes and flavours linger on in the palate? And why does it seem to be the least pleasant flavours that hang around?

Aftertaste or After-Odour?

Strictly speaking, taste refers to what we experience on the tongue: sweet, salty, sour, bitter, umami, and perhaps one or two others (e.g. MG Tordoff et al, 2012; CA Running et al, 2015). When we talk about aftertaste in coffee, we are usually really talking about the flavour — the combination of taste and aroma. Researchers sometimes use the terms ‘after-odour’ or ‘after-flavour’ instead, to distinguish these from aftertaste.

In this strictest sense, considering only basic tastes, the aftertaste of coffee is different to the taste when drinking it. Different compounds have different lengths of aftertaste: for example, caffeine leaves a longer aftertaste than quinine (EJ Leach & AC Noble, 1986). This means that the balance of tastes in the aftertaste will likely be different to the first sip.

However, the biggest difference maker when it comes to aftertaste lies in the flavour, rather than in the taste. This is the result of particular molecules remaining in the mouth longer than others after swallowing the coffee. These molecules pass into the nasal cavity through the back of the throat, so we continue experiencing their aroma after the bulk of the coffee has been swallowed. This is called ‘Retronasal olfaction’. The act of swallowing actually increases retronasal olfaction, as the movement of the pharynx pushes aromas into the nasal cavity (Buettner et al,, 2001).

Which Molecules Linger?

The aroma compounds that stick around for longest are thought to be the largest, and the least water-soluble molecules. Larger molecules are the least volatile, which means they don’t evaporate as easily. Aroma molecules need to vapourise in order to reach the nasal cavity, and the weight of larger molecules means they take longer to escape the liquid and reach the nose. Many of the larger molecules in coffee are those created from dry distillation in roasting — associated with woody, spicy, and ashy flavours (TR Lingle, 2011).

Less water-soluble molecules also stay in the mouth after swallowing, because they are more likely to be bound to or dissolved in the oils in coffee. After swallowing, fats and oils coat the mouth and retain odour molecules, which are released as gases or gradually dissolve into the saliva (JF Prinz & R de Wijk, 2004). The compounds that dissolve in coffee oils carry many of the bitter and roasty notes in coffee (J A Sánchez López et al, 2016).

The natural surfactants found in coffee, such as melanoidins, allow coffee oils to coat the mouth more effectively (Navarini et al,, 2004). Oils and melanoidins are particularly concentrated in espresso, which is one reason the aftertaste of espresso can be so long. Since both large molecules and less water-soluble molecules are associated with some of the less pleasant flavours in coffee, this explains why the aftertaste is generally less pleasant than the flavour of that first sip.

A Postscript on Wine

While we expect that it’s generally the larger and less water-soluble molecules that stay in the mouth, we don’t know exactly which molecules contribute to the aftertaste of coffee. Research in wine, where aftertaste has been studied in more detail, suggests that it may be down to more than just size and solubility.

In wine as in coffee, different flavours persist for different lengths of time, with the most volatile compounds, responsible for fruity or floral flavours, disappearing first. However, the polyphenols in wine interact with different flavour compounds in different ways — affecting both how we perceive them, and how easily they volatilise (AK Baker & CF Ross, 2014), which would influence their effect on the aftertaste. Coffee also contains polyphenols, which could have a similar effect.

In a study measuring directly which molecules were retained in the mouth, researchers found that one small and hydrophilic molecule called guaiacol stayed longer than expected in the mouth. Guaiacol is a small molecule that would be expected to dissolve easily in water, but the researchers speculated that polyphenols help it bind strongly to proteins on the inner surface of the mouth and therefore contribute to the aftertaste (A Esteban-Fernández et al, 2016).

The researchers hypothesise that this happens because of Guaiacol’s molecular structure. Guaiacol contains a phenolic ring, which binds to similar rings found in polyphenols. Molecules with this type of structure frequently contribute smoky, spicy, and medicinal aromas to coffee (I Flament, 2001). However, some related molecules also contribute positive flavours, particularly vanilla-like aromas — in fact, vanillin itself is a phenolic compound. Perhaps we have this effect to thank for some of the more pleasant flavours in the aftertaste of coffee.

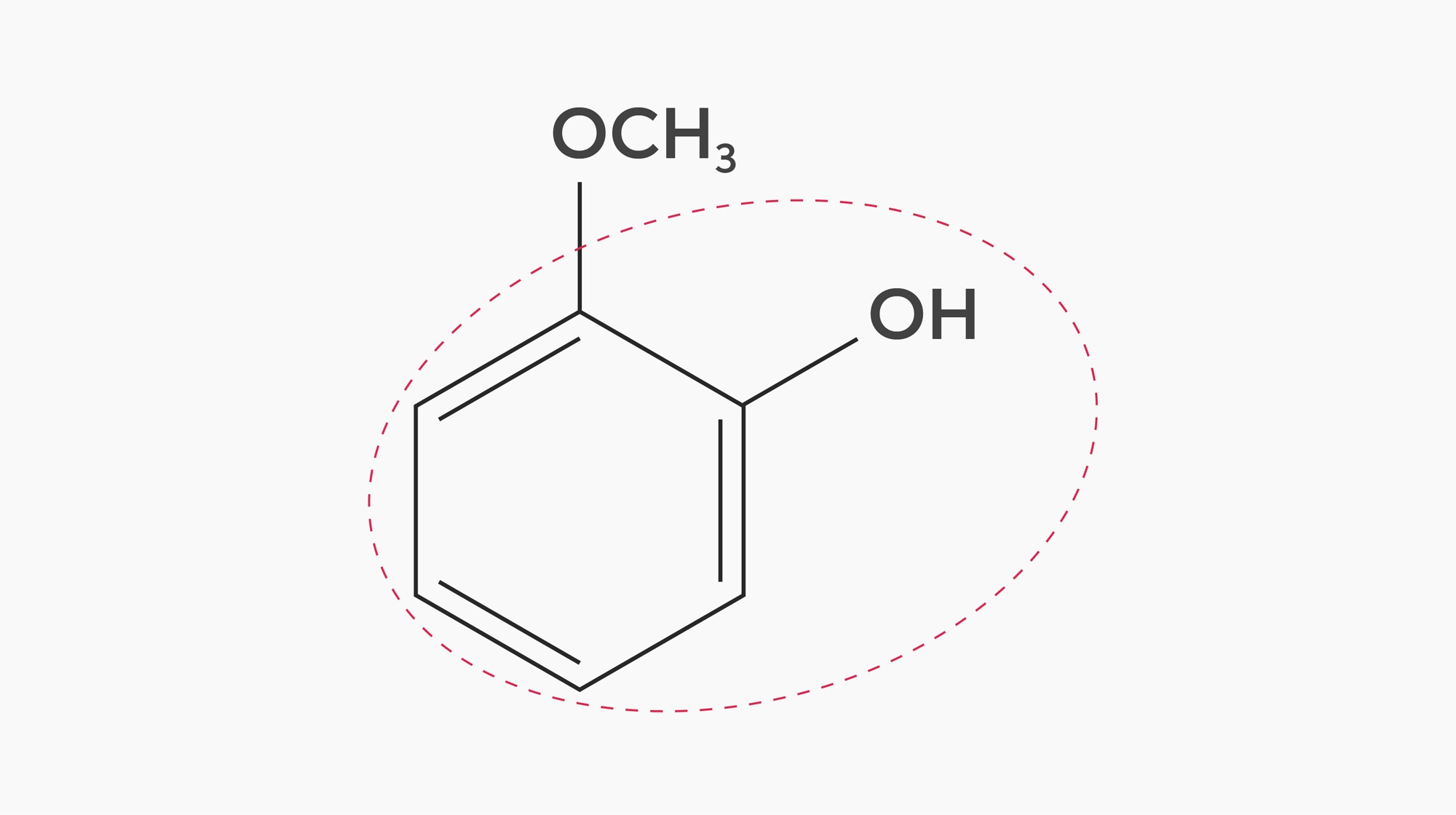

The molecular structure of Guaiacol, showing its phenolic ring (red dotted line).

The molecular structure of Guaiacol, showing its phenolic ring (red dotted line).

Hello there! I am a relatively new coffee blogger at the Coffee Collective, and a long-time coffee lover/enthusiast. In my years of coffee consuming I have often wondered about the after-taste coffee leaves behind at times, and why it varies. But, I never thought to look more into it until I saw this blog post. I must say this is incredibly informative and I am extremely glad to have been able to read it! Now, what I’m wondering though is this, is there a full-proof way to avoid the aftermath of a good coffee brew before it gets to be an unpleasant coffee after aroma?

Hey Mariah, Aroma is such a tricky thing that the first every 100-point scoresheet designed for coffee (The Cup of Excellence Scoresheet) developed by George Howell, decided to not score aroma because it’s so quick to change and can lead to different experiences for different people. It’s on the COE scoresheet but does not contribute to the final score. Super clean equipment and fantastic roasting of fresh green coffee is still the best way we know to avoid unpleasant aromas or aftertastes.