By Sebastien Delprat, with the collaboration of Mikael Janvier and Lucio Del Piccolo

Multi-part article – go to part: #1 #2

The Mysterious “Glasmaschine”

Even if Mühlbach is citing Schindler to underline the veracity of her story,[1] we should not forget that she was a historical fiction writer. Hence, even written in 1859, one should take her anecdotes on Beethoven coffee habits as historical fiction only.

Authors always want to add their own twist to stories, then from 60 beans and coffee prepared at home, it ends up with coffee in a metallic box, locked into a cabinet of Beethoven’s bedroom and water boiling before grinding the coffee (a matter that is never treated in any anecdotes).

That’s the same process which transforms the different designations “Glasmaschine”, “gläsernen Kolben” and “gläsernen Maschine” found in 19th century books, to only one word (“glass coffee maker”) in the later English translations, which becomes “Glass contraption”[2] in the internet era (appearing on many different articles) and then “Glass contraption of his own design” few years later.[3]

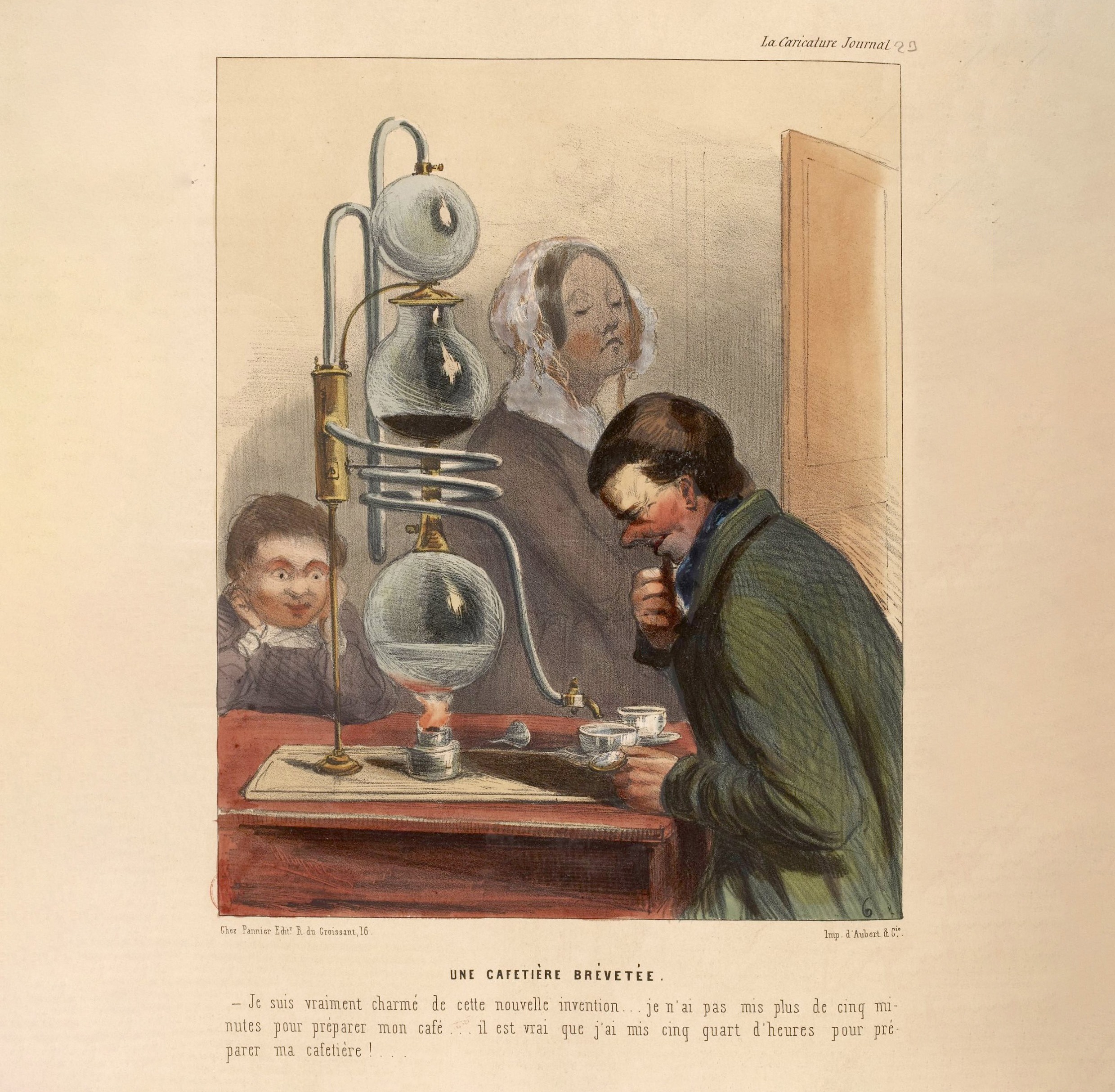

Drawing from “La Caricature morale, politique et littéraire”, June 4th 1843. [Source: Gallica.fr][4]

Drawing from “La Caricature morale, politique et littéraire”, June 4th 1843. [Source: Gallica.fr][4]

So let’s stick to the facts: Beethoven was regularly going to coffeehouses where he drank coffee in small cups. Otherwise, he had it every day for breakfast with a dosage of 60 coffee beans per cup (that he was precisely counting himself before making it). The coffee was prepared in a glass machine (or flask), which Beethoven often used himself, as it seems, directly on a table. At least, the machine was used to pour the coffee (sometimes directly on the writing table or the piano).[5] The coffee was “black” and “excellent” according to visitors.

What we have is only one direct witness of the “60 beans” routine (Anton Schindler in 1840) but three different testimonies on the use of a “glass machine” to prepare his coffee (Anton Schindler in 1860, Dr. Karl von Bursy in 1816 and Friedrich Starke between 1812 and 1840). We may have doubts on the first story that is so peculiar that witnesses should have also reported it… unless the scene always happened away from the visitor’s sight (in Beethoven’s kitchen for example) so only known by very close relatives of the great artist.

Most likely the coffee was grinded at the last minute and prepared in the kitchen. It was certainly not a coffee maker with its own burning lamp or one with a spectacular way of working (otherwise it would have been reported by different testimonials). But as for how the machine worked, if boiling water was poured or boiled in the machine, we have no precision (except from Mühlbach’s imagination).

Sixty beans of darkly roasted coffee (as it was the habit in Vienna if we rely on the “Vienna” roast characteristics) represents about 8g. It was many times argued that it is a bit too less for a drip coffee (recommended quantity is ~12g for 20cl of coffee), and that it corresponds precisely to the quantity necessary to prepare an espresso (and I won’t talk here of people fantasizing that the genius Beethoven invented the espresso machine). But all that depends on the size of the cup, that was pretty small compared to nowadays standards. On the other hand, 8g per cup for a “Turkish coffee” is almost exactly what it takes. Is that what Schindler meant by saying that his friend had “an oriental fastidiousness of taste”.

What about the glass machine? If he was just transferring the decoction into a glass vessel, to avoid the bottom deposit of the Turkish coffee, that vessel could not be called a “machine”… unless he filtered the decoction.

I searched a long time for any evidence of coffee use in Beethoven’s preserved personal objects. I didn’t find any. Really: no grinder, no coffee cup, nothing close to a coffee maker. The only authentic object preserved that can be close to a “Glasmaschine” or “gläsernen Kolben” is in the Beethoven’s Museum of Bonn. But it’s a gift from Beethoven to Franz Gerhard Wegeler: a drinking glass.[6] Nothing that can be called a “glass coffee maker”.

Glass object from Beethoven’s personal belongings [Credit: Beethoven’s Museum of Bonn]

Glass object from Beethoven’s personal belongings [Credit: Beethoven’s Museum of Bonn]

I also searched extensively for a representation of his house or studio in Vienna and found many portraits of the artist in his apartments. Only two of them show objects related to coffee: cups, and what looks like a porcelain coffee pot. Nothing conclusive, especially because these paintings were produced more than 70 years after Beethoven’s death.

The two Beethoven portraits showing him in his apartment with coffee-related objects

The two Beethoven portraits showing him in his apartment with coffee-related objects

The only coffee into a portrait, if I may say, is hidden in the first illustration of this article: as a matter of fact, Ferdinand Schimon who portrayed Beethoven in 1819 put a lot of effort into capturing the personality of Beethoven, especially the expression of the eyes. The great master was himself pleased with the result and Schindler finds it faithful to Beethoven’s character. According to Schindler (who used an engraving of the portrait for his book),[7] it is only after two invitations around a cup of coffee ‘with sixty beans’, that he managed to do so. Hence, what you see when looking at Schimon’s painting is a portrait of Beethoven under caffeine.

But, nowhere, any trace of a glass machine, even in the glimpse of Beethoven’s eyes.

If we roll back to history, the first striking thing is that, from what we know of the evolution of coffee makers, almost none were using glass material until the 1830s (many years after Beethoven’s death). The method to obtain glass that will not explode under heat or pressure was quite recent.[8] At the beginning of the 19th century, glass was just starting to be used on what was the beginnings of modern chemistry. As a matter of fact, the first known glass machines were inherited from the scientific world.

One was invented by a German Physicist named Johann Gottlieb Christian Nörrenberg in 1827 (the year of Beethoven’s death). In his publication,[9] he writes that the machine was assembled “last winter” (hence no sooner than late 1826) to explain Aeolipile principle to his students and explicitly use it as a coffee machine. It is the very first siphon machine, which was later copied by his French friend Jean-Baptiste François Soleil, first in metal, then in glass from the 1830s.[10]

Drawing of the Nörrenberg coffee maker, appearing in his scientific report from 1827.

Drawing of the Nörrenberg coffee maker, appearing in his scientific report from 1827.

Earlier than 1826, the only other example of what could be designated as a “glass coffee maker” is an apparatus called the “couloire”, invented around 1795 by the French chemist François-Antoine-Henri Descroizilles. It was created to obtain Sodium carbonate solution from limestone but was also used as a coffee maker by Descroizilles who was a great amateur of coffee (as testified by contemporaries). It is the ancestor of the drip coffee maker (still falsely named “DuBelloy”).[11]

Drawing of the “Couloire” appearing in Descroizille’s book.[12]

Drawing of the “Couloire” appearing in Descroizille’s book.[12]

As can be seen on the drawing from his scientific book, the apparatus uses a tin part (with a filter and a funnel) mounted onto a glass bottle. Nothing special about the bottle, it is expressly described as a regular wine bottle. Could this be called a “Glassmaschine” by Beethoven’s contemporaries? I have a doubt, but it could explain why it was thrown away after Beethoven’s death. If Beethoven’s machine was very peculiar, why wasn’t it kept for posterity?

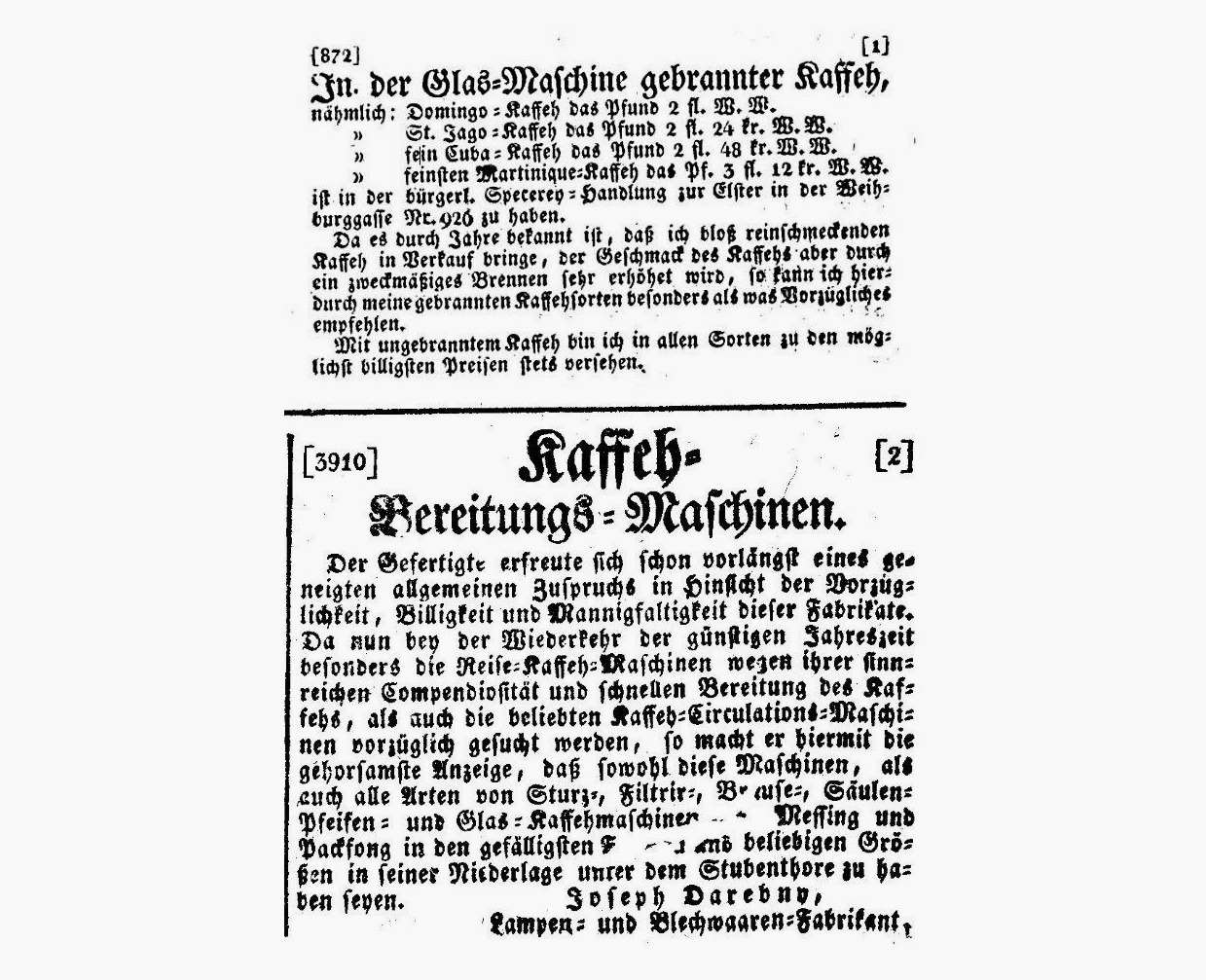

I also asked myself if there were glass coffee makers available in Vienna at the time. Why not: as we will see later, there are still lots of archives lost in the limbs that can reshape the historical narrative. The only occurrences of the word “Glasmaschine” I found in journals before the 1840s are from 1831 and 1834. The first one proposes coffee “roasted into a glass machine”, the second one is from a manufacturer selling “Coffee-making machines” of different types with, among them, a “Glasmaschine”. But that is 7 years after Beethoven’s death. It may correspond to the beginning of siphon coffee makers, a bit earlier than France but not so much surprising since the idea first originates from Germany.

Two extracts from Austrian Newspapers mentioning coffee “Glasmaschine” (top one from 1831[13] and bottom from 1838[14])

Two extracts from Austrian Newspapers mentioning coffee “Glasmaschine” (top one from 1831[13] and bottom from 1838[14])

The Beethoven “Glasmaschine” hence remains a mystery. What could it be?

Is it possible that he used a very advanced machine, not yet available to the public? He was indeed connected to lots of different people from the intelligentsia and aware of many advances in science, as his notebooks could prove. From now, until a solid proof arises, we can only speculates that he prepared coffee “à la Turque” (that was the most common way to prepare it at the time) and, eventually, filtered it to obtain a decoction without deposit, using a glass vessel (that way it could be witnessed as prepared “on the table”, with what could be abusively called a glass machine by visitors, but how could we blame people from the early 1800s for not being coffee makers specialists?). The other hypothesis is that he was an early adopter of drip coffee, but making small volumes (comparable to small cups found in coffeehouses), hence from a relatively small quantity of freshly ground coffee.

Is that it? No, here comes a very interesting untold story.

On the track of Ignaz Meissner

From 1825, Beethoven was suffering so much that his personal doctor, Braunhofer, advised him not to drink wine and coffee anymore.

“Braunhofer treated Beethoven from spring 1825 and seems to have held his own against his stiff-necked patient. After all, Beethoven stuck to the prescribed diet and abstained from alcohol and coffee, as the doctor had advised him.” [15]

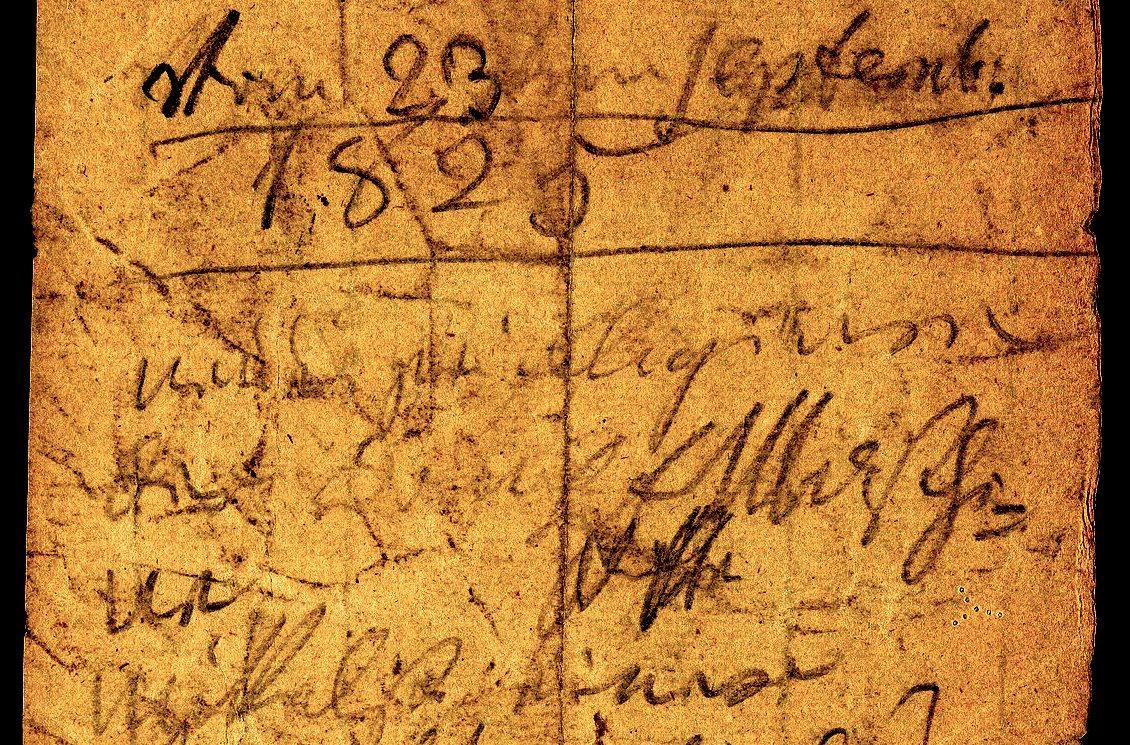

If he followed that diet, he was still very interested in coffee machines… as testifies a relic found only by chance at the end of the 19th century. A piece of paper, sold at an auction in 1891, that looks detached from the Dead Sea Scrolls, showing a very difficult to read handwriting.

Note hand-written by Beethoven from September 23th, 1825 [Credit: Beethoven’s Museum of Bonn]

Note hand-written by Beethoven from September 23th, 1825 [Credit: Beethoven’s Museum of Bonn]

Dr. Theodor Frimmel was called to the rescue[16] and he managed to decipher it. On this hand-written note from September 23th 1825, attributed to Ludwig van Beethoven himself, appears the word “Kaffeemaschine”.[17] It is so difficult to read, even knowing what’s on it (can you recognise the word “Kaffeemaschine” above?) :

“From September 23th, 1825 — new privilege of the newest coffee machine by means of a device which presses the aroma released by the hot vapors through blotting paper with such force that not even a single atom can remain in the leached coffee powder, thereby saving money and speeding up the process.”

Frimmel was certainly deceived by what he found, but for the world of coffee lovers, this is invaluable information on what a journalist calls “the great Beethoven’s little bourgeois habits.”[18] More than that, it allows a search for this precise machine, because the note refers directly to an article that Beethoven red the same day on the front page of the Wiener Zeitung:[19]

Wiener Zeitung, September 9th 1825, p.1.

Wiener Zeitung, September 9th 1825, p.1.

What is totally incredible is not only that Beethoven is pointing to a new development in coffee makers technology at a very early stage of their evolution, but that nearly 200 years after his death, he helped us[20] make a great discovery.

The article reads:

“His Imperial and Royal Majesty has already, by His Highest Resolution of November 15th, 1823, granted Ignaz Meissner, technical chemist in Vienna, resident in town number 532, a five-year privilege in accordance with the provisions of the Supreme Patent of December 8th, 1820, to improve his privileged coffee steam machine, which he had acquired on June 14th, 1820, by adding a device, namely an air press, which presses the aroma released by the hot steam through blotting paper with such force that not a single atom can remain in the leached coffee powder, thereby achieving a great saving in coffee, no other coffee extract can equal the coffee extract produced in this way, and the process gains in speed. This is brought to the public’s attention with the statement that the medical faculty has no objection to the exercise of the privilege in Samtäts-Rücksfichten, and that the Imperial and Royal Polytechnic Institute has otherwise guaranteed the permissibility of the use of the machine.”

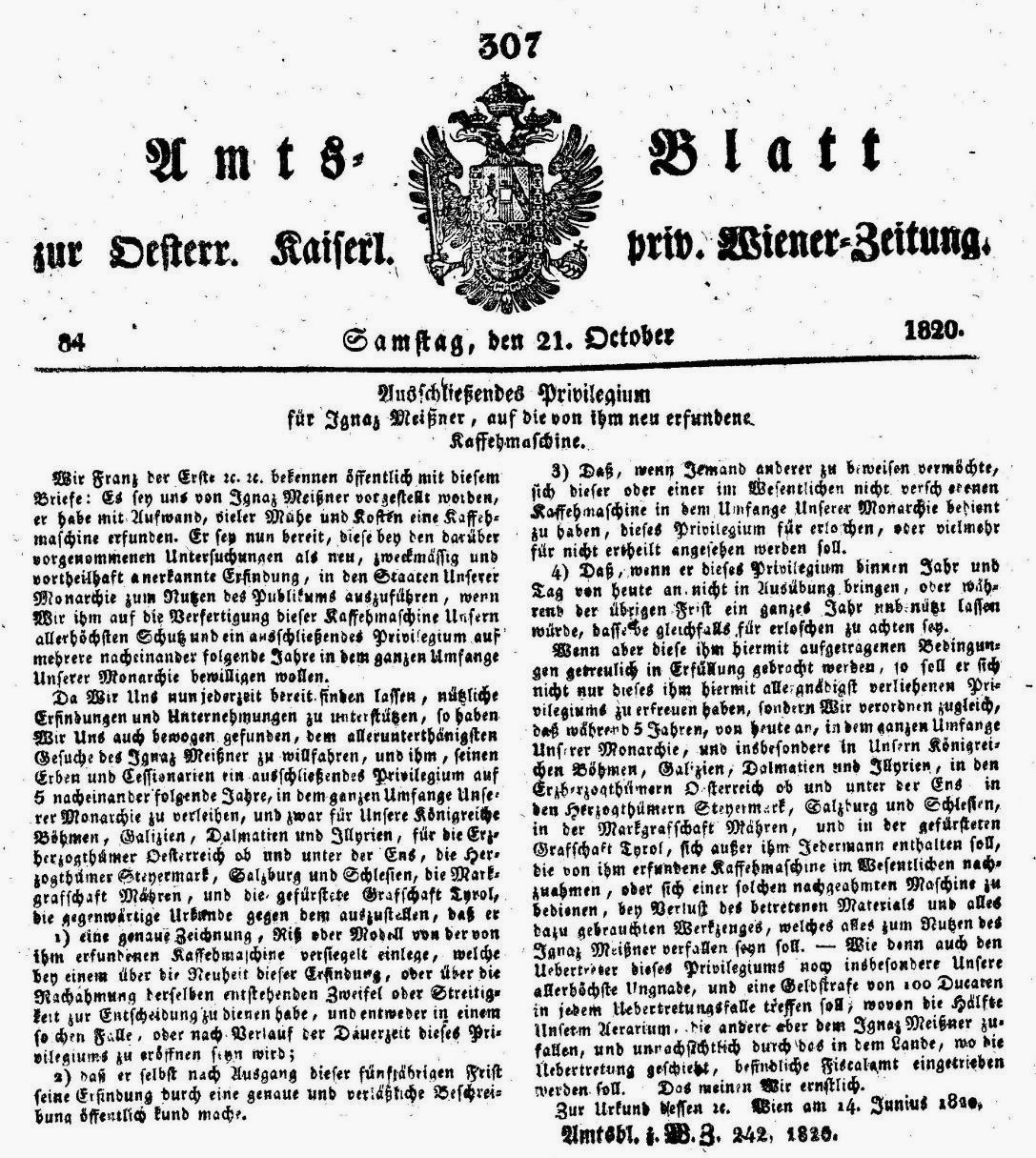

It namely refers to another patent, from June 14th 1820 that was also announced in the Wiener Zeitung in 1820:

Wiener Zeitung, October 21st, 1820, p.5[21]

Wiener Zeitung, October 21st, 1820, p.5[21]

“We, Franz the First, publicly confess with this letter: We have been told by Ignaz Meißner that he has invented a coffee machine with great effort, trouble and expense. He is now ready to implement this invention, which has been recognized as new, practical and advantageous in the investigations carried out on it, in the states of our monarchy for the benefit of the public, if you are willing to grant him Our highest protection and an exclusive privilege for several consecutive years throughout the entire scope of our monarchy for the manufacture of this coffee machine.

[…] he 1) submit a sealed, precise drawing, outline and model of the coffee machine he invented, which will serve to decide any doubt or dispute that arises about the novelty of this invention or about its imitation and will be disclosed either in such abundance or after the expiry of the term of this privilege;

[…] everyone except him shall refrain from imitating in any way the coffee machine invented by him, who shall use such an imitation machine, with the loss of the material used and all tools used for it, all of which shall be forfeited to the benefit of Ignaz Meissner. As well as this, the violator of this privilege shall incur Our highest displeasure and a fine of 100 ducats in each case of violation, half of which shall go to Our tax office, the other half to Ignaz Meissner, and shall be collected without penalty by the fiscal office in the country where the violation occurs. We mean this seriously.”

This is certainly what happened to Karl Delavilla, who was sued by Ignaz Meissner in 1824 for violation of his invention and had his patent canceled.[22] We can also find that Ignaz Meissner’s machines were fabricated by Karl Demuth, in Fünfhaus near Wien and could be bought at Mayerhoffers in Leopoldstadt.

It was not Beethoven’s machine since it was invented in 1820 whereas he was using his glass machine since (at least) 1816. But what did that machine look like? It took all the research skills of Mikael Janvier and all the resources of Lucio Del Piccolo, my dear colleagues and friends, to find it. And… in a morning of January 2025, opening a folder that was certainly manipulated only by archivists for the last 200 years, Mik found it.

Here it is, the Ignaz Meissner machine :

Ignaz Meissner original patent drawings from 1820 and 1825, with its signature showing “Technischer Chemist” [Credit: Mikael Janvier, Archiv der TU Wien]

Ignaz Meissner original patent drawings from 1820 and 1825, with its signature showing “Technischer Chemist” [Credit: Mikael Janvier, Archiv der TU Wien]

The patents show what is called a pumping percolator: it uses the steam pressure to push water through a tube, here external (which makes the originality of the design), and brings it to the upper part of the machine, where the coffee powder is. It then passes through the powder, and the extracted coffee falls down in the middle part. It is nothing else than the very first version of automatic drip machines.

The second patent adds a very ingenious system on the pumping tube: a one-way valve, consisting in a ball blocking the passage in the downstream direction.

Even more incredible, there is one Meissner machine still in existence today, somewhere in Trieste, Italy. Trieste used to belong to the Austrian Empire at the time of its invention. This jewel stands among many other incredible jewels of the great Lucio Del Piccolo collection.

Machine from the private collection of Lucio Del Piccolo, badge with the double-headed eagle (typical of the Habsburg and Austrian Empire) reads “Meißner Ignatz” [Credit: Lucio Del Piccolo]

Machine from the private collection of Lucio Del Piccolo, badge with the double-headed eagle (typical of the Habsburg and Austrian Empire) reads “Meißner Ignatz” [Credit: Lucio Del Piccolo]

Different machines with that design (based on the Laurens principle but with an external pipe and great care attached to the machine’s appearance) exist. Different versions on its origins can be found: sometimes attributed to S. Jones,[23] and more recently to Jacques-Augustin Gandais[24] (even if his 1827 French patent mentions that the machine is imported from Germany).[25]

History always evolves along new discoveries: last year, an Italian machine was found, pushing back the invention date down to 1824.[26] The machine pointed out by Ludwig van Beethoven in 1825 is not only the same machine but is the oldest example of its type known so far, as proven by the Austrian patent granted to Ignaz (or Ignatz) Meissner (or Meißner) in 1820, which is pretty clear on the novelty of the concept.

Patents drawings from Gandais (Left) and Jones coffee makers (right), respectively 1827 and 1829. [Credit: INPI and Dinglers Polytechnisches Journal]

Patents drawings from Gandais (Left) and Jones coffee makers (right), respectively 1827 and 1829. [Credit: INPI and Dinglers Polytechnisches Journal]

Thanks to Beethoven himself, we not only have found the original patent of the first external pipe “pumping percolator”, another machine from a chemist, but also identified with certainty one machine that still exists today (thanks to Mikael Janvier who found the place to look and went in person to the archives in Vienna, and to the tremendous collection of Lucio Del Piccolo).

That’s not Beethoven’s glass machine but that was really worth the investigation.

To the memory of Ian Bersten (April 4th 1939 – September 11th 2022)

[1] See Part 1/2 of the present article

[2] The Daily Beethoven, “Beethoven’s Kitchen” by Ed Chang (October 1st, 2010).

[3] Blake Stilwell (February 12th, 2021), Opus cit.

[4] Comment reads : “- I’m really charmed by this new invention… it didn’t take me more than five minutes to make my coffee… it’s true that it took me five quarters of an hour to prepare my coffee maker!…”

[5] “Literarischer Zodiacus – Journal für Zeit und Leben, Wissenschaft und Kunst“ by Dr. Th. Mundt (1835), p.191.

[6] NE 81, Band IV, Nr. 676, Beethoven’s Museum of Bonn.

[7] This story was added as a complement to the 1860 edition, and appears on p.452 of the English translation.

[8] In a report from 1820 in the Polytechnisches Journal, the “Means to protect glass from shattering” are still discussed… and the cited solution is the same as a “remark made in 1811 by a waiter in a coffeehouse in Lyon, where, as is well known, coffee is served in glasses.”

[9] “Beschreibung einer Kaffehmaschine” Zeitschrift für Physik und Mathematik, Vol.3 (1827) p.269-271.

[10] “Ascenseur pour l’Expresso, Episode 4“ on Cafeo(b)logue, by S. Delprat (2013)

[11] “Ascenseur pour l’Expresso, Episode 1“ on Cafeo(b)logue, by S. Delprat (2013)

[12] From “Notices sur l’alcali-métre, et autres tubes chimico-métriques ou sur le polymétre-chimique” by François Antoine Henri Descroizilles (1824).

[13] “In der Glas-Maschine gebrannter Kaffeh” in Wiener Zeitung (December 27th 1831, p.17).

[14] “Kaffeh-Bereitungs-Maschinen” in Wiener Zeitung (April 21st 1838, p.14).

[15] Sammlung H. C. Bodmer, HCB BBr 105, Beethoven’s Museum of Bonn.

[16] “Beethoven und die Kaffeemaschine“ in Grazer Tagblatt (November 11th 1891, p.18).

[17] BH 56, Beethoven’s Museum of Bonn.

[18] Grazer Tagblatt (November 11th 1891), Opus cit.

[19] “Wien” in Wiener Zeitung (September 23d 1825, p.1).

[20] I mean the coffee community, but especially the ARTiC squad (Lucio Del Piccolo, Mikael Janvier and myself)

[21] “Ausschließendes Privilegium für Jgnaz Meißner, auf die von ihm neu erfundene Kaffehmaschine” in Wiener Zeitung (October 21st, 1820, p.5).

[22] According to the article “Rundmachung” (2d column), in “Der” Bote von Tyrol (July 22d, 1824).

[23] Implicitly in “All about coffee” by William H. Ukers (1922) p.504. In “Coffee Makers – 300 years of art & Design” by Edward & Joan Bramah (1989) p.71: the author puts the same date, 1827, on a “French design” (without citing Gandais) and the “Jones of the Strand” design. In “Coffee floats, tea sinks” by Ian Bersten (1993) p.74 : the author was certainly misled by a typo error on a printed Dinglers Polytechnisches Journal because the cited date (1819) is also wrong. In fact, S. Jones of the Strand patent for a “Self-acting coffee pot” is from 1829, as mentioned in Dinglers Journal or The Register of Arts and Journal of Patents from 1829.

[24] “CoffeeMakers – Macchine da caffe” by Enrico Maltoni, Mauro Carli and Lucio Del Piccolo (2013, 2020) p.108.

[25] “Ascenseur pour l’Expresso, Episode 6“ on Cafeo(b)logue, by S. Delprat (2014).

[26] Lucio Del Piccolo and Mikael Janvier, private communication.

0 Comments