Kessel and the portafilter milestone by Sebastien Delprat

Kuchen-Kaiser, conditorei and café (founded in 1871) in a photo dating to the beginning of the twentieth century; the business is still located at 11–13 Oranienplatz.18

Kuchen-Kaiser, conditorei and café (founded in 1871) in a photo dating to the beginning of the twentieth century; the business is still located at 11–13 Oranienplatz.18

Ideas are always spreading and piling up. Some are so ready to spring out that they emerge at multiple places at the same time. More often, innovations are the result of a long process of small steps paved by many different people. Sometimes, fabrication techniques must evolve in order to allow the realisation of new concepts. The industrial revolution that introduced steam-driven machines also profited other domains, such as the conception of the espresso machine.

History tells the story of Archimedes shouting ‘Eureka!’ after he was struck by a thought that seemingly came out of nowhere. But, rather than an instantaneous insight, an invention is more commonly a very slow infusion (or decoction) of ideas that takes place in a specific context and answers a specific need. And no matter how much effort or money is spent to promote its success, an invention’s chance of reaching the public is usually a matter of luck and circumstances.

And for that rule to be perfectly true, we just need a counter-example: Gustav Adolf Kessel.

The primary commonalities between Etzensberger and Kessel are that they spoke German, and both had enterprises that used steamers traveling through a canal … and those facts support only a very weak correlation. They occurred in different parts of the globe and in absolutely different areas of activity.

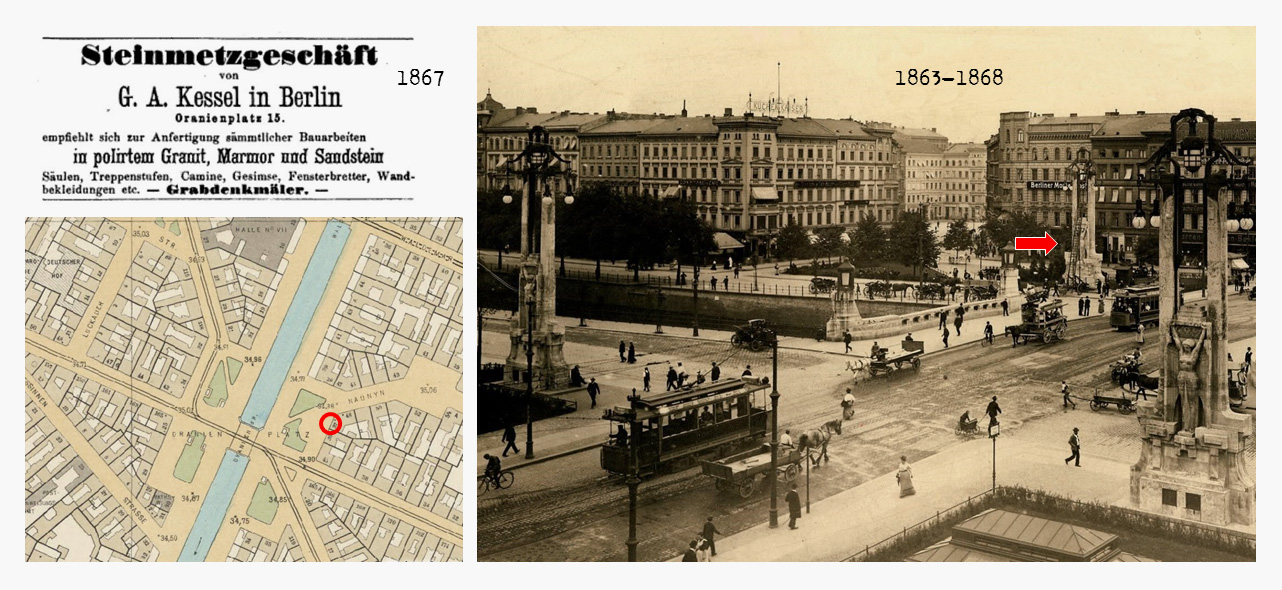

The first known address of Gustav Adolf Kessel in Berlin, where he had his business from 1863 to 1868

The first known address of Gustav Adolf Kessel in Berlin, where he had his business from 1863 to 1868

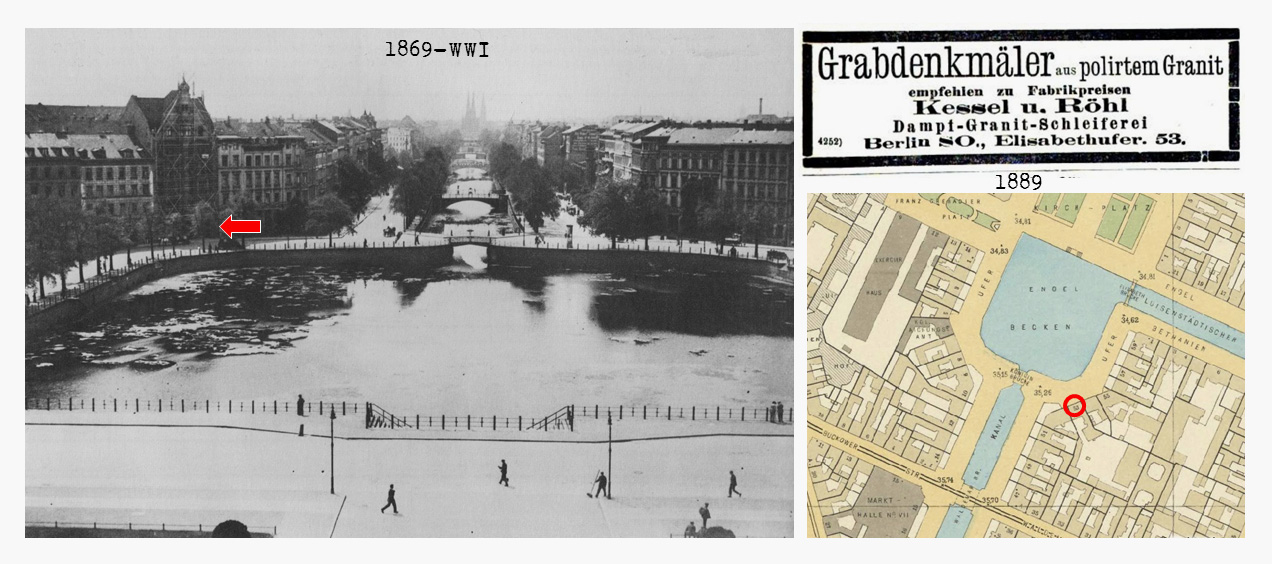

The address of Kessel’s business in Berlin, from 1869 until the First World War (in association with Hermann Röhl)

The address of Kessel’s business in Berlin, from 1869 until the First World War (in association with Hermann Röhl)

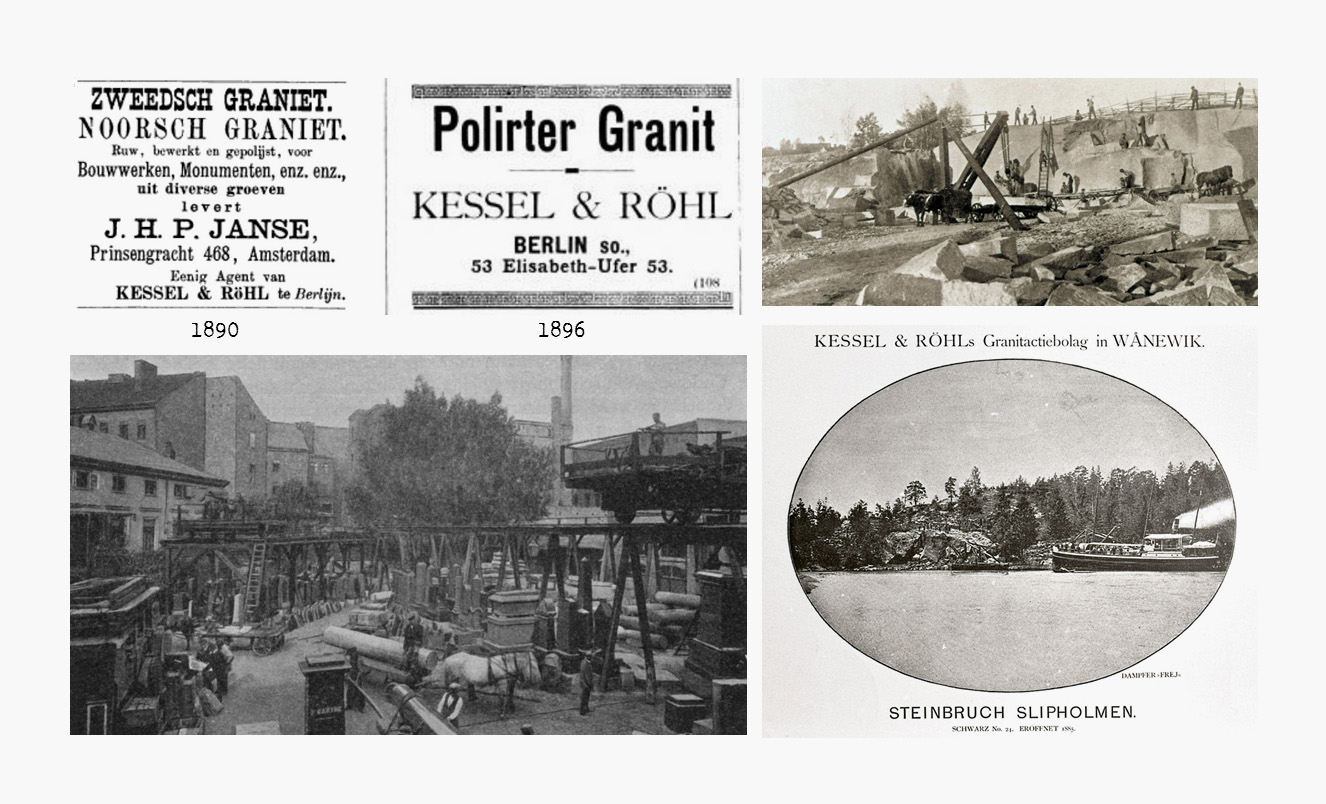

Gustav Adolph Kessel used the ‘Luisenstädtischer Kanal’, located in the Kreuzberg neighborhood. The waterway opened in 1852 and was filled in during the 1920s. Kessel utilised the canal for his business activities related to granite and stonemasonry from 1863 until the onset of the First World War. Early on, he partnered with Hermann Röhl to create the Kessel & Röhl company. Their specialized business, formed at the time of the rise of the German Empire, became one of the leaders of the stone industry in Europe. In 1869, Kessel moved his activities along the canal from the 13 Oranienplatz19 (right next door to the Kunchen-Kaiser, one of the coffee institutions of Berlin that still exists today) to 53 ElisabethUfer20 (the actual 13 Leuschnerdamm, where a famous art-deco building still stands today, called the Engelbecken-Hof). Kessel’s steamboats carried giant blocks of limestone, granite, and marble down the canal. His company obtained stones from quarries in Sweden and Norway and exported them for the construction of monuments as far away as Philadelphia (for a monument to George Washington).

During the late nineteenth century, the Kessel & Röhl workshops, located in central Berlin, transformed giant blocks of granite and marble sourced from Sweden and Norway.

During the late nineteenth century, the Kessel & Röhl workshops, located in central Berlin, transformed giant blocks of granite and marble sourced from Sweden and Norway.

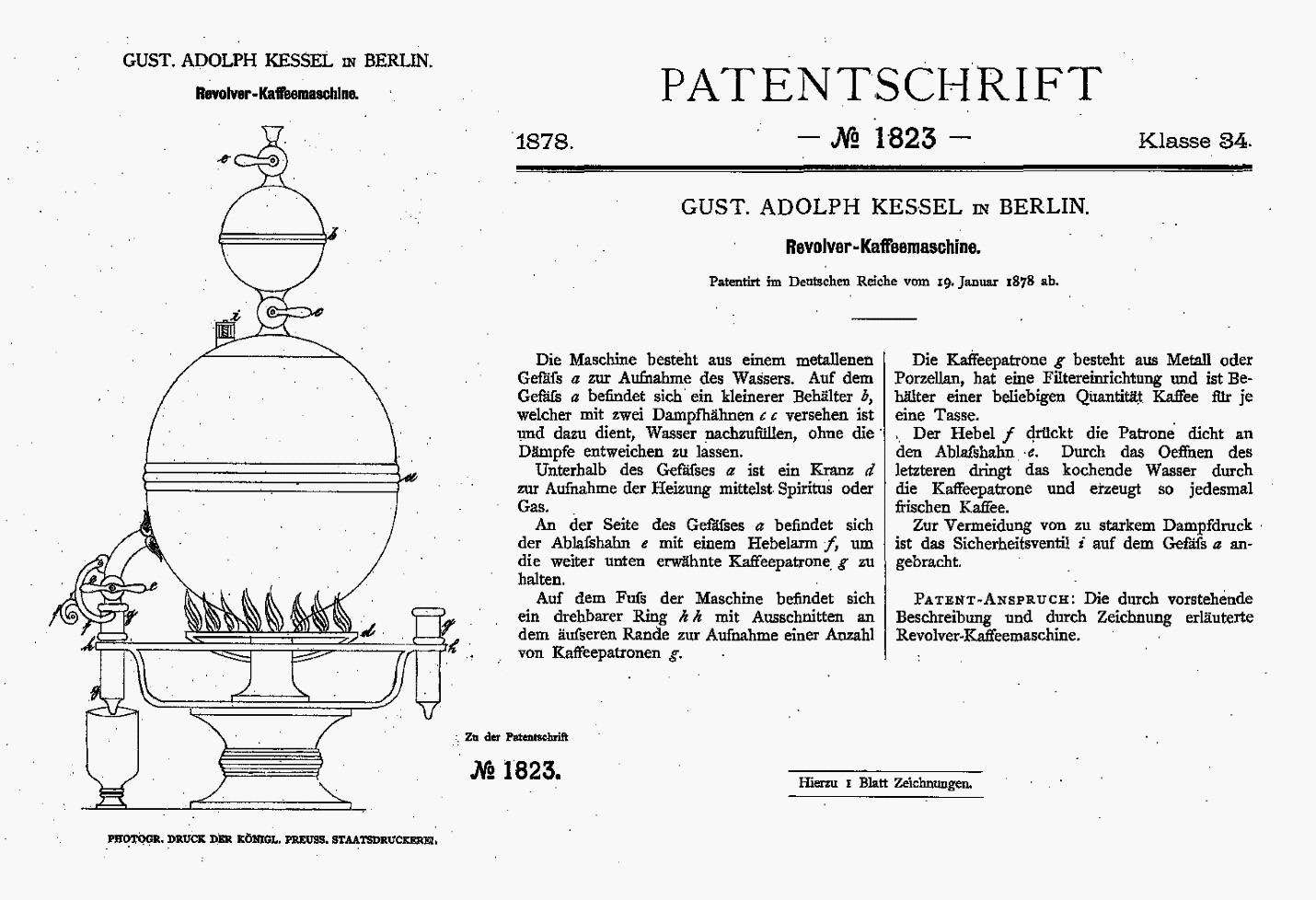

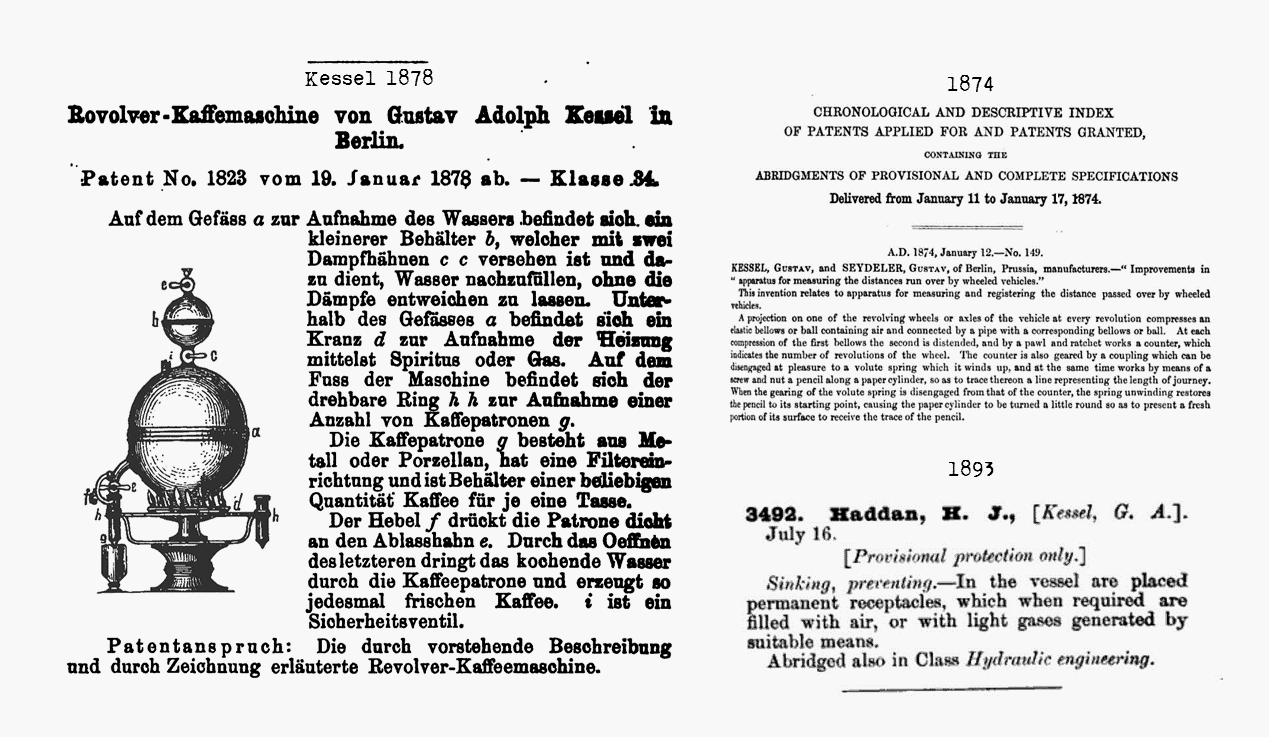

Kessel’s links to the world of coffee are a mystery, but something must have struck him in the middle of his business ascension. His invention, titled ‘Revolver Coffee Machine’, is described in a short patent from 1878, and indeed this invention sounds like an unexpected gunfire. His machine, presented in the same year that Eicke introduced his small espresso coffee maker, has almost all the features of the espresso coffee machine — six years ahead of Moriondo’s and 23 years before Bezzera’s.

The machine is a water boiler that can be refilled from above, and it is equipped with a safety valve and a steam-pressured water outlet tap. Single cartridges of metal or porcelain, mounted on a carousel, hold grounds for preparing a single cup of coffee. These cartridges attach to the tap by a locking mechanism. The analogy with a gun barrel is quite explicit and describes a very rapid way to prepare single cups of coffee in successive pours. Those certainly can be called the very first coffee ‘shots’.

The German patent from Gustav Adolph Kessel, filed in 1878 and titled ‘Revolver Coffee Machine’

The German patent from Gustav Adolph Kessel, filed in 1878 and titled ‘Revolver Coffee Machine’

A mention of the Kessel patent in the 1879 Illustriertes Patent-Blatt and the name ‘G. Kessel’ on other patents from 1874 and 1893

A mention of the Kessel patent in the 1879 Illustriertes Patent-Blatt and the name ‘G. Kessel’ on other patents from 1874 and 1893

This invention seems to have ‘come out of nowhere’. For sure, it is really the same Gustav Adolf Kessel, the founder of Kessel & Röhl; the address on other patent documents leaves no doubt about it. He lived in an expensive neighbourhood, next door to a famous coffeehouse in Berlin. Nothing seemed to predestine him to such an idea, neither his stone business nor his trips to northern countries. Maybe some visits at World Fairs, where he participated as an exhibitor, inspired him, or perhaps it was simply a passionate hobby that his business activities prevented him from further developing. Maybe it was just too soon and at the wrong place. Looking at different patent registries, it is not clear whether or not he participated in other patents. Only two other mentions of a ‘Gustav Kessel’ or ‘G. A. Kessel’ appear in the records: one in 1874 for an odometer and the other in 1893 for a boat safety system. They could be linked to him, but they are far from being related to coffee.

It is clear to me that Kessel, with his 1878 invention, is the true inventor of the espresso machine principle. His patent contains the most important elements of Moriondo’s later machine. But since it is unlikely that Kessel ever built a prototype of it, how can he claim a choice place in the historical record? Moreover, there is no obvious connection between him and the other known inventors, no trace of an article echoing his efforts to find a means of making good coffee on an elegant machine as fast as possible for single customers.

Two things were missing from his design, though: first, a standard-shaped boiler, but secondly and more importantly (as compared with Moriondo, Bezzera, and La Pavoni systems), the possibility to inject steam onto the coffee reservoir and/or release the pressure built above it at the end of the extraction.

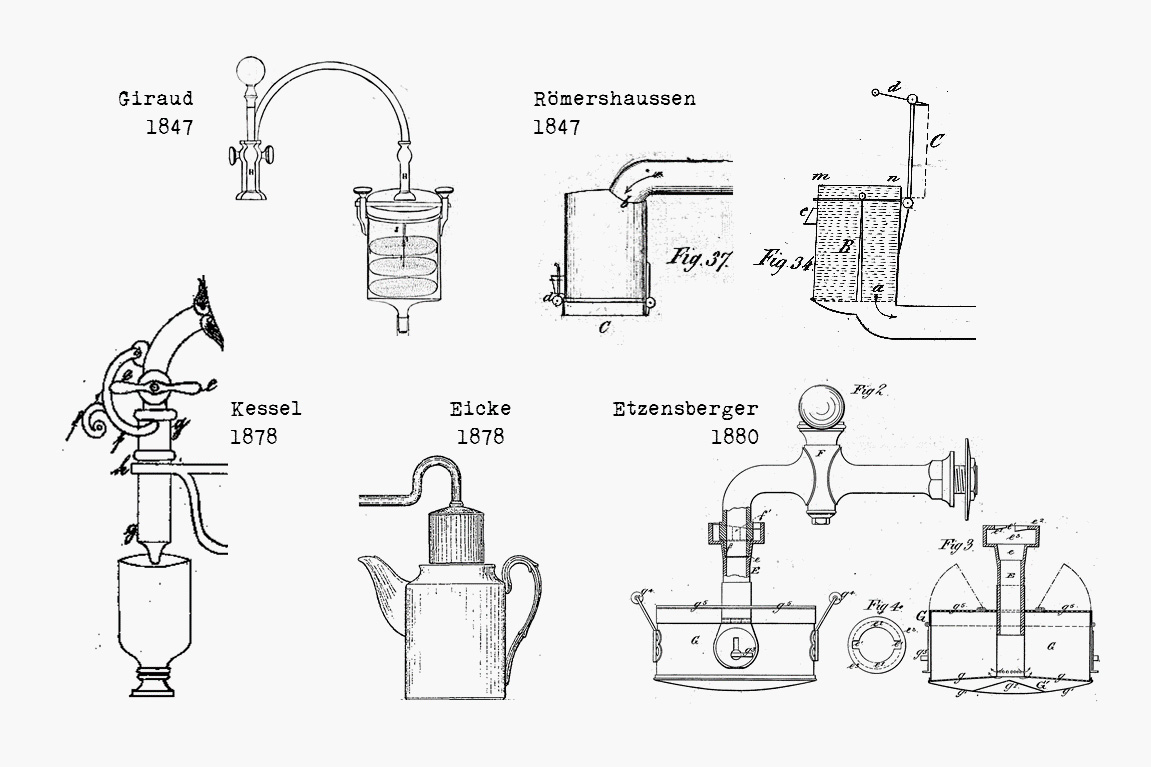

The evolution of ‘espresso’ brewing systems, with their respective ‘portafilter ancestors’. From 1847–1880, these systems featured only one outlet of steam-pressured water.

The evolution of ‘espresso’ brewing systems, with their respective ‘portafilter ancestors’. From 1847–1880, these systems featured only one outlet of steam-pressured water.

The evolution of ‘espresso’ brewing systems, with their respective ‘portafilter ancestors’. After 1884, systems used two position outlets: one for steam-pressured water and another for steam.

The evolution of ‘espresso’ brewing systems, with their respective ‘portafilter ancestors’. After 1884, systems used two position outlets: one for steam-pressured water and another for steam.

Apart from the elegance and style of his machine, this is what really makes Moriondo’s invention unique in the evolution of espresso brewing systems: Angelo Moriondo was the first person who cared about precisely dosing the quantity of water for the extraction. His machine used the steam separately to push water through the ground coffee, and it released the pressure built in the brewing chamber through another valve, thereby reducing the likelihood of burns to the machine operator. He spent a long period (from 1884 to 1910 and three patents) perfecting that idea. In that context, Bezzera’s and Pavoni’s patent present just small improvements to Moriondo’s invention.

That precise moment in the evolution of coffee machines was the result of a long search for a method to quickly brew coffee and, at the same time, extract the best from its flavors. The idea of using steam-pressured water to achieve that goal had been around for a long time (since, at least, Rabaut), and so was the use of an external coffee reservoir (Giraud, Römershausen), and efforts to ease its refill with freshly ground coffee were really on their way (Kessel, Eicke, Etzensberger).

From that perspective, the main contribution from Luigi Bezzera seems to be the use of a portafilter. Whereas Moriondo’s system was very basic, with a basket and attachment to the tap with a small handle maintained by a rack, Bezzera’s portafilter (termed a ‘filter-support’ in his patent) was very close to the one used nowadays by baristi — at least, if we base that assumption on very early pictures of his machine, since Bezzera or Pavoni were not very explicit about its shape in their patents.

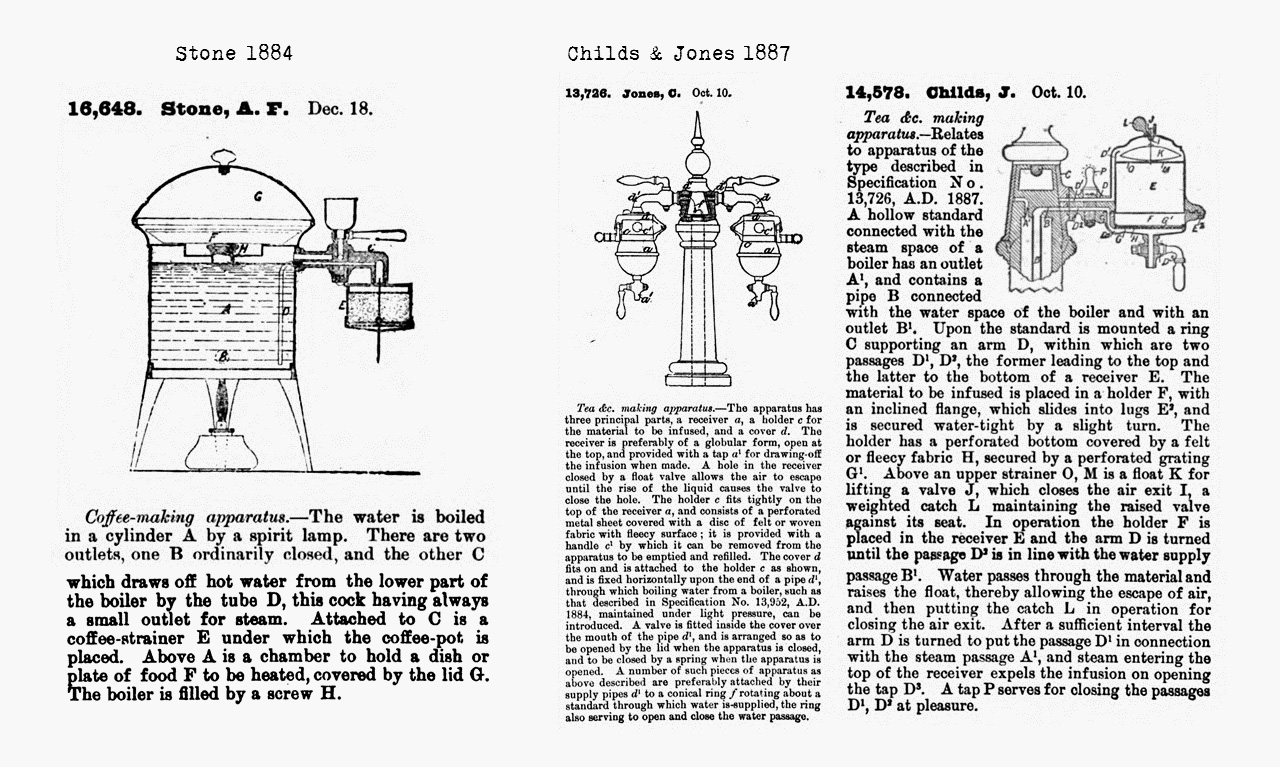

Patents show inventions related to the evolution of portafilters, with coffee machines from Arthur Flintoff Stones in 1884 and Childs & Jones in 1887

Patents show inventions related to the evolution of portafilters, with coffee machines from Arthur Flintoff Stones in 1884 and Childs & Jones in 1887

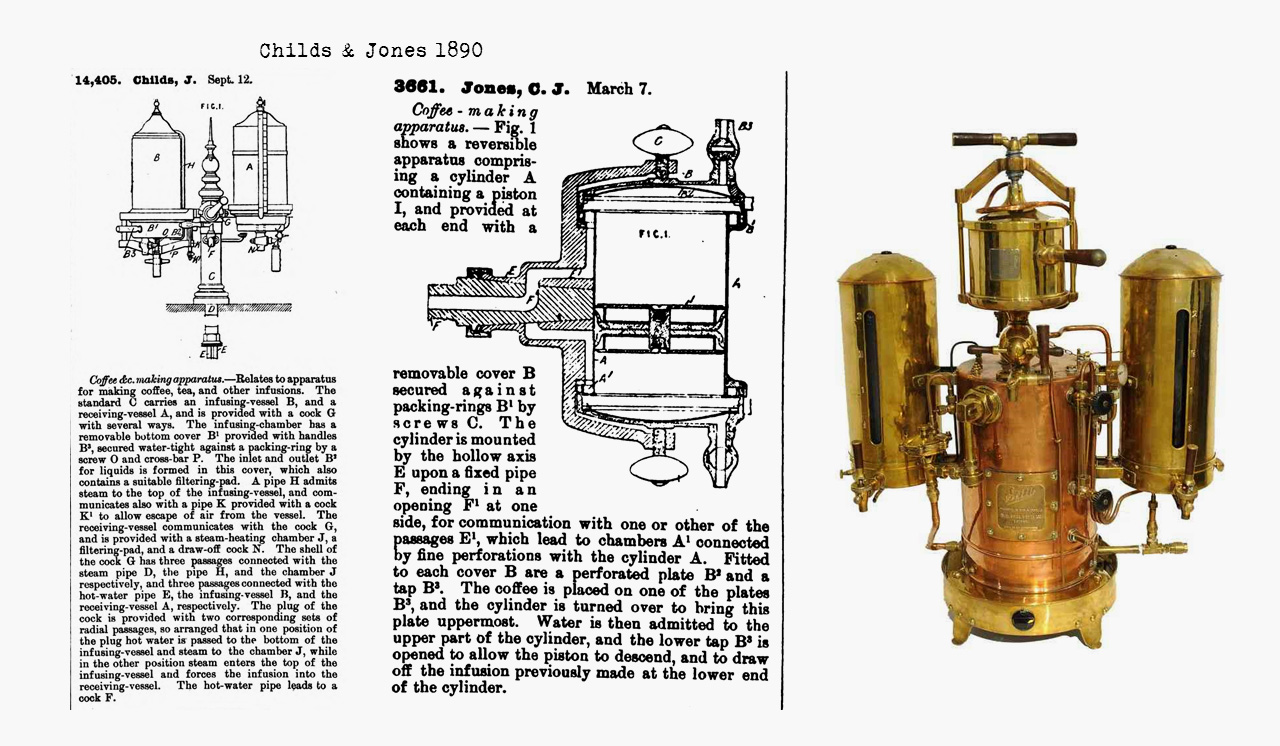

Childs & Jones patents and a coffee machine from the 1890s, sold by W. M. Still and Sons (London)

Childs & Jones patents and a coffee machine from the 1890s, sold by W. M. Still and Sons (London)

If we look at the different ‘filter supports’ invented before Bezzera’s time, it is obvious that the concept had been evolving., It is worth mentioning that in the same year that Moriondo patented his system, Arthur Flintoff Stone (from London) created one that was very compact, attached to the hot water tap by a threaded rod screwed from below. His machine could also be used as a plate warmer and was equipped with a steam release valve (for the boiler only). But, as in all the other inventions before his, there was no way for operators to remove that strainer without burning their hands.

The first ones to find a practical way to reload ground coffee into the machine (apart from Kessel and his barrel principle) were James Childs and Charles John Jones, from London, in 1887. Like Arthur Stone, these inventors are totally ignored by reference books, but their invention really represents the missing link between Moriondo and Bezzera. First, they attached a small handle to the holder in order to remove it from the tap, so it could easily ‘be emptied and refilled’ (as explicitly mentioned in the patent), making it the oldest portafilter known so far. Second, they developed a system that allows consecutive use of water and steam, on Moriondo’s principle and working almost exactly like Bezzera’s ‘group’ (except that the whole group turned on a vertical axis, not a horizontal axis passing through the tap).

Childs and Jones made many other inventions related to coffee- and tea-makers. C. J. Jones later partnered with William Mudd Still (the founder of W.M. Still and Sons Ltd, in 1874), and their designs slowly evolved toward giant percolators rather than espresso machines. Some of these apparatuses, constructed and sold by the W.M. Still company during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, survived time, and they exhibit a kind of giant portafilter.

(Counter-clockwise, from left) An Ideale filter-holder placed on the machine for extraction; positioned beside a modern portafilter for comparison; and with the basket removed. (pictures courtesy of Paul Pratt)

(Counter-clockwise, from left) An Ideale filter-holder placed on the machine for extraction; positioned beside a modern portafilter for comparison; and with the basket removed. (pictures courtesy of Paul Pratt)

Going back to Luigi Bezzera … we cannot be certain that he heard about Childs & Jones inventions, but as a vermouth producer and a bartender in Milan, it is quite likely that he heard about Moriondo’s invention. Nevertheless, like many others, he left his mark on espresso machine history and deserves his place in the hall of fame of inventors, along with Desiderio Pavoni, if only for spreading the usage of the espresso machine — and the portafilter.

Okay, so, who really invented the espresso machine?

I worked hard to present to you all the elements that I know to help answer that question. It is now your turn to think about it. Depending on your definition of ‘espresso’, your preference between outsiders or mainstream characters, and maybe your nationality or other considerations, I’m sure you’ll be able to find your own answer. I hope you also find answers to some other questions that you never considered before.

18 Photo from the Mein Sammlerportal website

19 View the actual address on Google Street.

20 View the actual address on Google Street.

0 Comments