Grinding burr technology is like the black box in an aircraft. We can see what we put in, and we can measure what we get out, but there is very little publicly available knowledge about what happens inside the grinder, and why certain designs work the way they do.

The debates about whether conical or flat burrs are better, the role of fines in espresso brewing, and what RPM a grinder should run at, are yet to be resolved. However, what is widely accepted is that roller mill grinders, with their enormous cylindrical burr sets and multi-step grinding, give the best control over grind size distribution and can potentially produce the best coffee.

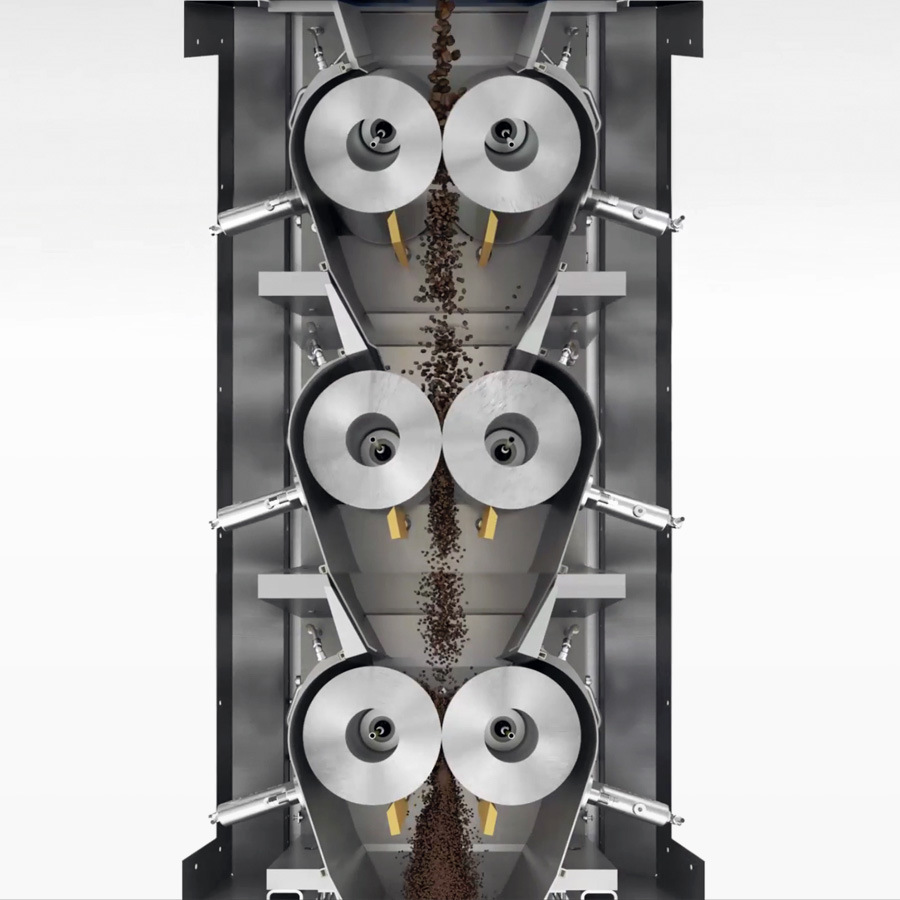

Types of coffee grinder (from left): Flat burrs, conical burrs, rollers. Roller mills usually grind the coffee in three separate stages.

The possibility of adapting a multi-step grinding process to change the particle size distribution in disc grinders is an intriguing one, and has been explored in different ways, from hybrid burr sets to multi-step grinding workflows involving single dose grinders.

For this post, we experimented with a double grinding workflow for espresso, using conventional espresso equipment, to explore what effect it has on extraction and flavour. Grinding twice required us to grind a lot coarser, suggesting that a lot more fines were produced, and resulted in lower extraction yields. However, what surprised us is that even with the lowered extraction, the resulting espressos had noticeably improved flavour and texture.

The Origins of Double Grinding

The idea of adapting a multi-step grinding process for use in disc grinders has been around for a while. In the 2014 World Brewers Cup, the Czech champion Petra Střelecká was breaking open beans to remove chaff before grinding. The next year she parlayed this into a two-step grinding process, starting with a coarse grind and then regrinding at a finer setting.

At the 2017 World Barista Championship, the Japanese champion Miki Suzuki took the approach a step further; freezing the beans before each grinding step, in a deliberate attempt to increase the production of fines and to maximise the available surface area of her coffee. Since fines are the main contributors to extraction in espresso, increasing fines production can increase extraction — but overdoing it can cause flow through the puck to clog, causing channelling.

Fines are the tiny particles (<100μm) that are created each time a coffee particle is ‘cut’ by the burrs inside a grinder. Since grinding twice means each particle can be cut more times, it can also be expected to increase the amount of fines produced. This is highlighted by Nuova Simonelli’s findings when designing the clump crusher for the Mythos One: if the crusher creates too much resistance to coffee exiting the grinder, then the coffee particles circulate in the burr set several times. This ‘regrinding’ resulted in excessive fines production and had to be carefully controlled for in the final design.

On the other hand, feeding the coffee into a grinder more slowly, whether already coarsely ground, or as whole beans, results in fewer fines being produced. Without the resistance created by coffee already in the burrs, coffee particles can travel through the burrs more quickly and therefore get cut fewer times on their passage through the grinder. This approach was suggested by engineer Tom Jagiello and featured in a James Hoffmann video last year.

Double Grinding in Practice

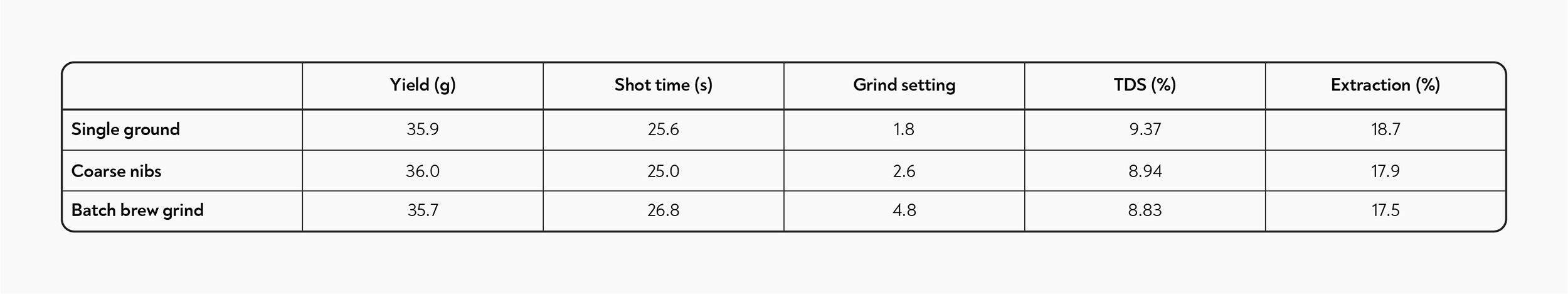

We designed our experiment around espresso, using a fixed shot time as a way to define a nominal ‘grind size’, and thus create a meaningful comparison between different grinding methods. We made shots using our standard workflow with a K30 espresso grinder, using the same dose (18.0g) and yield (~36g) each time and dialing in the grinder to produce shots of around 25-27 seconds.

Stages in double grinding (from left): Coarsely broken nibs of coffee, a coarse batch brew grind, and the final espresso grind.

We made three sets of espressos: one set using whole beans, one using beans pre-ground at the coarsest setting on a standard EK43 (a very coarse batch brew grind), and finally one using large ‘nibs’ of coffee, producing by recalibrating an EK43 to grind as coarsely as possible.

To account for factors such as the grinder heating up during the experiment, or changes in atmospheric conditions, we alternated between the different methods. The hopper was loaded with the same amount of each type of coffee, to minimise any effect of the weight pushing coffee into the grinding chamber. We made 6 shots for each set of espressos and measured the extraction immediately after pulling each one.

As expected, we found that the pre-ground coffee needed a much coarser grind setting to produce the same shot time. The finer the initial grind, the coarser the final grind setting needed. The extraction followed the same pattern — the whole beans produced the highest extraction, followed by the coarsely broken nibs, and finally the pre-ground coffee produced the lowest extraction of all.

The difference between single grinding and double was statistically significant (p<0.01), while the difference between pregrinding to coarse nibs or batch brew size was not (p~0.1). There was no correlation between extraction and shot time or yield.

These results are in line with what might be expected: grinding the same coffee twice produces more fines, necessitating a coarser grind setting to get the same shot time, and lowering extraction — supposedly because of increased channelling.

However, the taste results didn’t match this picture at all. The single ground shots were not particularly pleasant — we had dialed them in for a fixed shot time, not for best flavour. They tasted tart, salty, and roasty, with bitter almond flavours. The shots that had been ground at the batch brew setting first, on the other hand, were much sweeter and smoother, tasting more like sweet almond and dark chocolate with a tangy acidity, and a striking creamy texture. If the lower extraction was caused by channelling, this is very much not the flavour profile we would expect to see. We tasted this difference over several shots, and found that the coffee ground as coarse nibs had a flavour profile somewhat intermediate between the two.

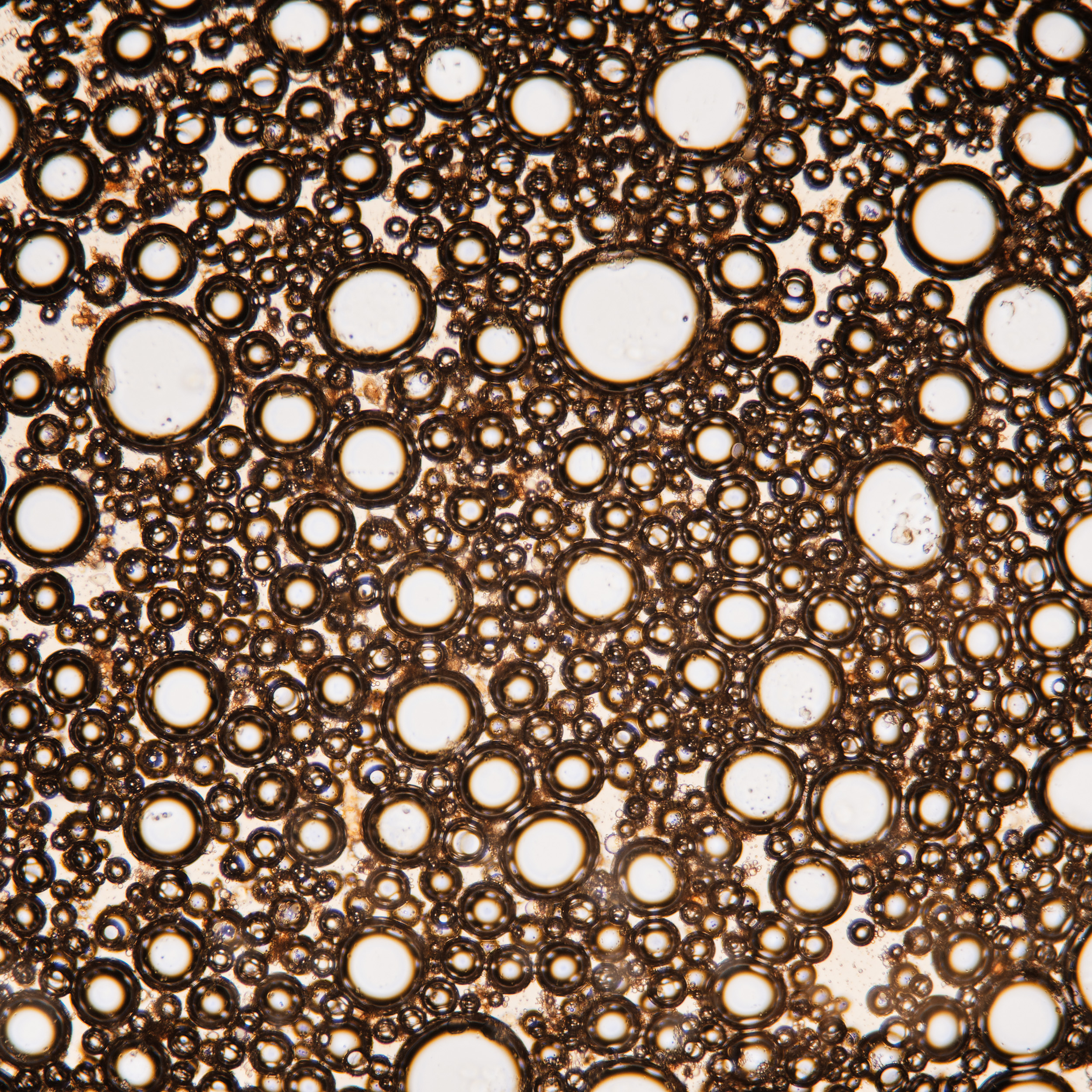

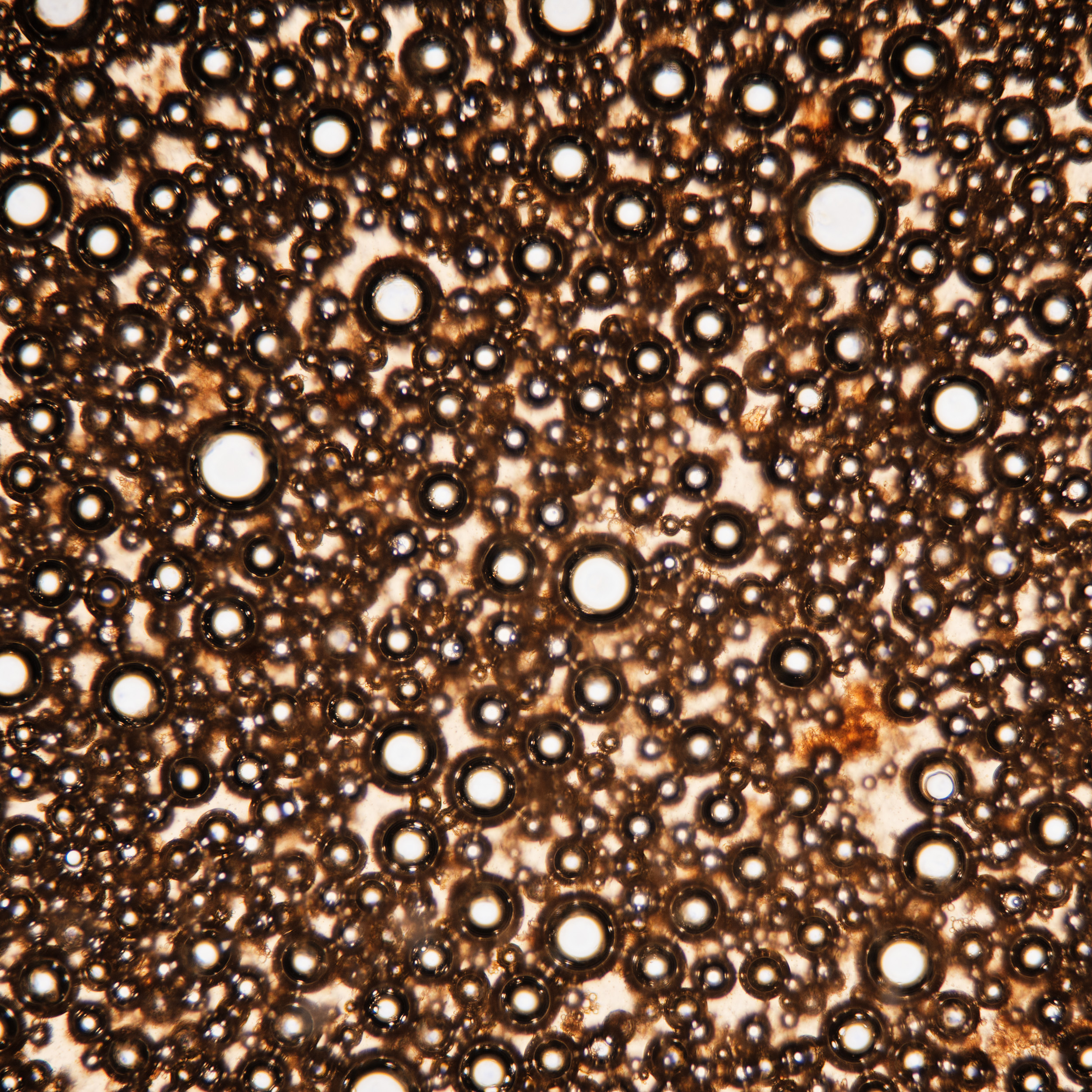

Double grinding results in a thicker, more stable crema with smaller bubbles. On the left is crema from a standard shot, and on the right the crema from a double-ground shot. Both pictures were taken using a light microscope at 10x magnification.

Comparing single and double-ground espressos. The double-ground espresso (right) has a thicker crema with a shiny surface thanks to the smaller bubbles compared to the standard espresso (left).

One other interesting characteristic we noticed is that the double-ground shots had thicker, and very shiny crema. We checked the crema out under the microscope and were able to see that with double grinding, the crema has smaller bubbles, which presumably accounts for the glossy texture and better persistence. This is in line with Jonathan Gagné’s observation that espressos made with ‘low-fines’ burrs “had way less crema…and when any crema was visible, it disappeared a lot more quickly”.

Discussion

The results suggest that double grinding is increasing the amount of fines produced, but the conflicting results regarding extraction and taste are puzzling. Since the initial shots were not dialled in to produce the best flavour, it’s possible that if we had chosen a different recipe as the basis of the experiment, we would have had different results. It would be interesting to try dialing in both methods for flavour and comparing the results, although this would be a very subjective exercise.

However, the fact that feeding bean fragments into the grinder more slowly has the opposite effect to what we saw in our testing suggests a possible link to the effect of changing the grinder RPM. Grinding more quickly has a similar effect to grinding finer — producing more fines and lowering the mode grind size.

Perhaps pre-grinding the coffee is producing a similar effect to increasing the RPM, by filling the burr gap with crushed coffee particles before the coffee has a chance to make its way out of the grinder. Conversely, perhaps feeding in the coffee slowly is functionally equivalent to a lower RPM, because it gives the ground coffee plenty of time to escape the burrs before more coffee is added. Just like pre-grinding, increasing the RPM also seems to decrease extraction slightly for a given shot time, at least in a Mythos 2.

This implies a possible link between double grinding, the ‘popcorning’ effect of feeding beans slowly into the grinder, and changing the grinder RPM — that the effect of each of these is to change the balance between the rate of coffee entering and exiting the grinder. In each case, choosing the slower-grinding option seems to result in higher extraction, less fines and a more modal grind size, which would be expected to improve flavour. Why we found the opposite effect on flavour in our experiment remains a mystery.

In a future post, we plan to analyse the particle size distribution of the coffee ground this way, to test some of our assumptions about what double grinding is doing to the coffee. We’ll also try dialing in both the single and double ground coffees for flavour, rather than to a specific recipe, to find out what the effect on the maximum potential quality is.

What an interesting article about double grinding, the cup taste and crema definitely tells regrinding has its advantage, fascinating! MOMENTEM dual-burr hand grinder will be the future, we will do more test and share the result. Thanks for the article. BH.