Last month, we wrote about why you might want to shake your grounds before making espresso. Lance Hedrick’s testing showed that shaking was somehow dramatically increasing extraction in his espressos, while simultaneously decreasing shot time. We explored a few possible reasons why this might be, from elimination of static to the mysterious process known as densification (for an explanation of densification, take a look at our previous post on this subject).

But our post, and Lance’s findings, raised more questions than they answered. Was it shaking alone that had this effect, or is there something special about the Weber Workshops Blind Shaker he used in his tests? Can shaking by hand really create enough force to mimic the effects of densification? And should shaking be combined with other distribution methods, or should it replace them entirely?

We set out to explore shaking in more detail, and were surprised to find we got quite different results than Lance did. In fact, our results completely contradicted most of the theories we had about how shaking might work. We also tested out the effect of shaking on flavour — and the results were a lot less positive than we had hoped.

Shaking and Shot Time

One of the most striking things about Lance’s results was that shaking increased extraction, while simultaneously decreasing shot time. This points to extraction being more efficient, and suggests that shaking could be used to allow a finer grind without clogging up the basket.

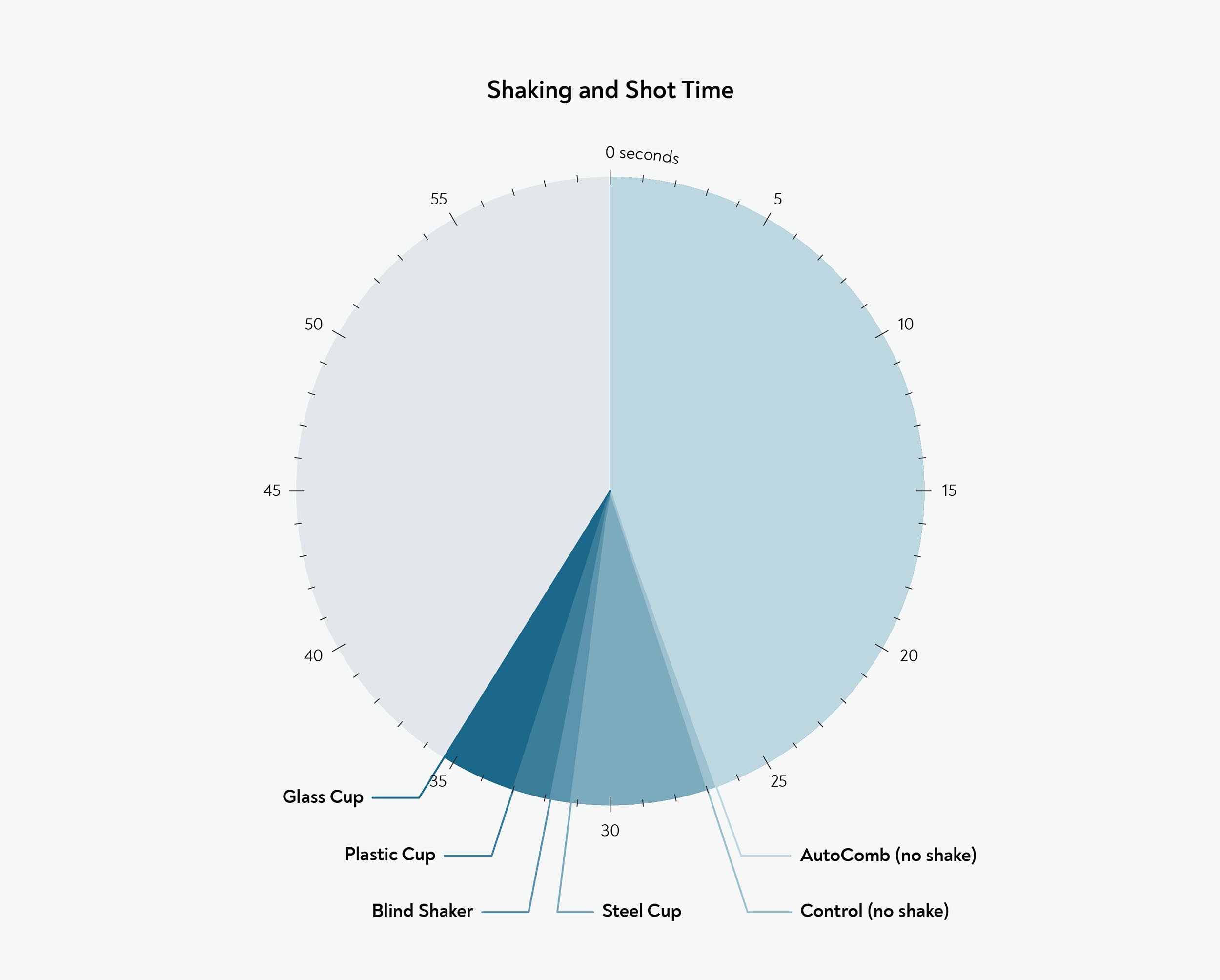

Right off the bat, our results contradicted this finding. In our first test, we compared shaking to our standard method of making espresso, and found that it made our shots run noticeably slower. We tried shaking in cups made from several different materials, as well as Weber’s Blind Shaker, and the results were the same each time.

Shaking increases shot time, no matter what material cup is used. Each measurement is the average of five shots.

Shaking increases shot time, no matter what material cup is used. Each measurement is the average of five shots.

We also noticed that far from decreasing the effect of static, the shaken grounds seemed to clump together more — to the point that they were sometimes hard to get out of the container. Even the Blind Shaker — with its nice polished interior — was not immune.

Shaking in the Weber Workshops Blind Shaker created visible clumps, and caused grinds to stick to the inner surfaces.

Shaking in the Weber Workshops Blind Shaker created visible clumps, and caused grinds to stick to the inner surfaces.

Our first thought was that this could be due to the particular equipment or coffee we were using. So to see if shaking would have the same effect in a different setting, using more typical shop equipment, we asked our friends at Origo Coffee in Bucharest for help.

Testing Shaking Behind the Bar

Miruna Tudose is the manager of Origo Coffee’s flagship shop, in Bucharest’s Old Town. She agreed to carry out the experimental work for us — and to give us feedback on the effect of shaking on the flavour of the espresso.

She made a series of espressos with different methods: shaking with the Blind Shaker, shaking with a polypropylene cup, using the Autocomb, and with no additional distribution method as a control. She made five shots of each, twenty shots in total, using a Mythos One to grind each dose. She measured the TDS of each shot, and tasted each shot together with the baristas on her team.

Miruna wielding a Blind Shaker behind the bar at Origo Coffee

Miruna wielding a Blind Shaker behind the bar at Origo Coffee

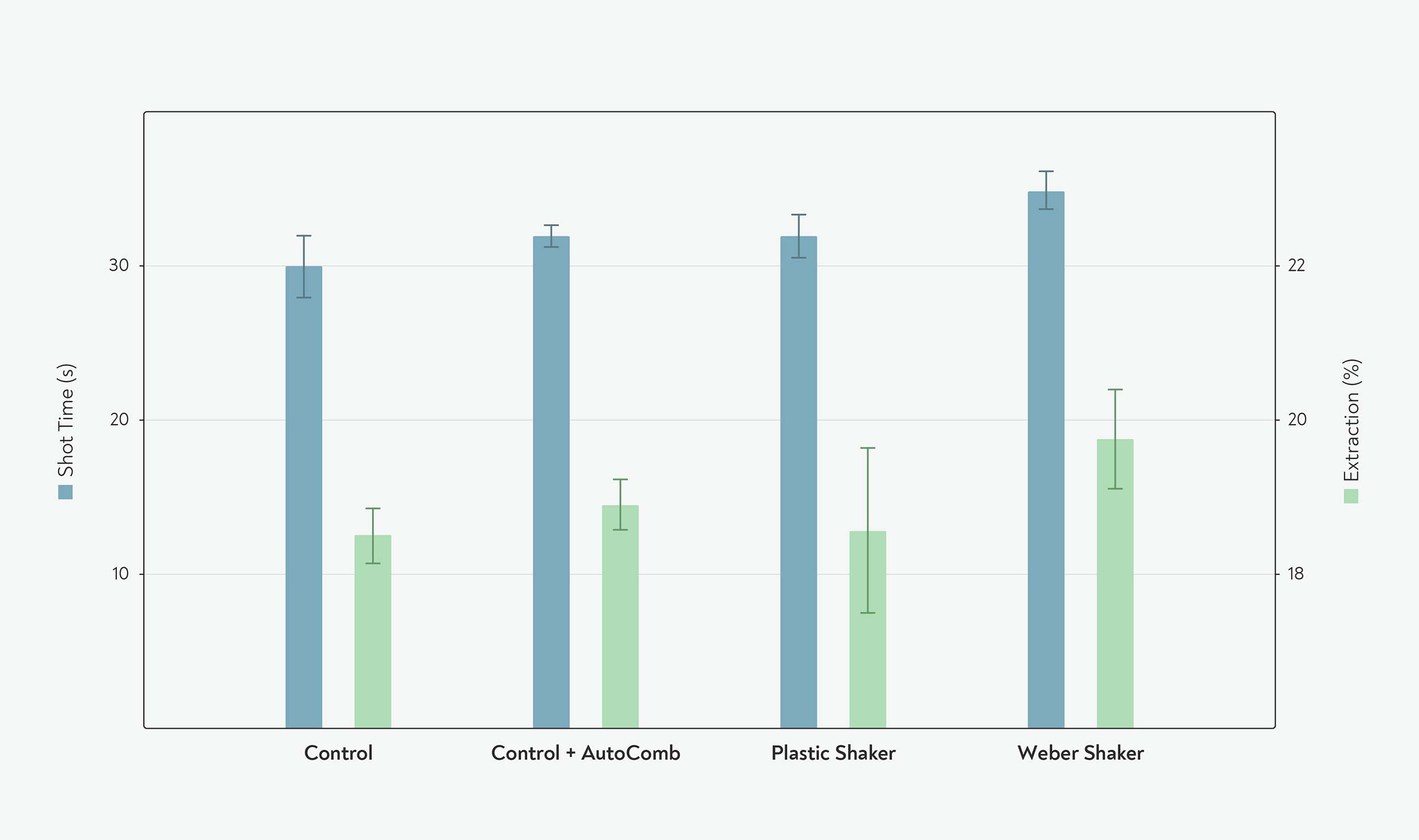

Miruna found that using the Blind Shaker boosted extraction by more than a percentage point — similar to the boost in extraction that Lance saw in his tests. However, unlike Lance, she also found that shaking in the Blind Shaker made her shots run more slowly. The difference was small (3–5 seconds), but statistically significant when compared to all other methods.

Shaking in the Blind Shaker increased extraction, but also increased shot time. Error bars represent one standard deviation.

Shaking in the Blind Shaker increased extraction, but also increased shot time. Error bars represent one standard deviation.

In contrast to Lance’s tests, we also saw a significant (but smaller) increase in extraction when using the Autocomb. The standard deviation for both shot time and extraction percentage was also smallest when using the Autocomb; in our tests, shaking made the shots much less consistent.

Since extraction also increased with shot time in these tests, the difference in extraction with the Blind Shaker could potentially be explained entirely by the difference in shot time. If this is the case, then we could potentially get similar results simply by grinding a touch finer. In Lance’s tests, by contrast, the extraction went up even though the shot time was shorter — indicating something more interesting happening in his tests.

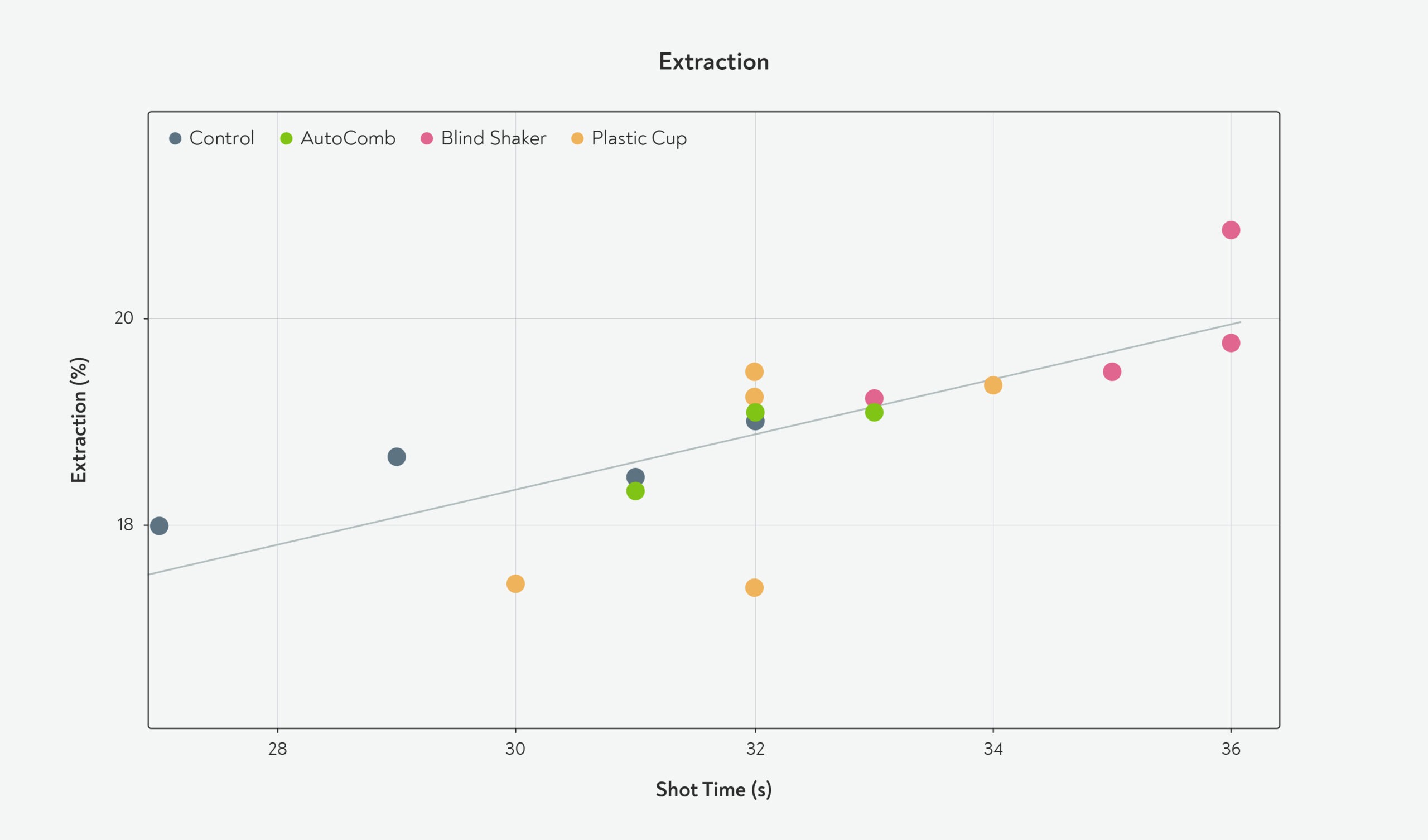

Extraction increases with shot time. Shots with the Blind Shaker had higher extraction, but the shot time alone could be enough to account for the difference.

Extraction increases with shot time. Shots with the Blind Shaker had higher extraction, but the shot time alone could be enough to account for the difference.

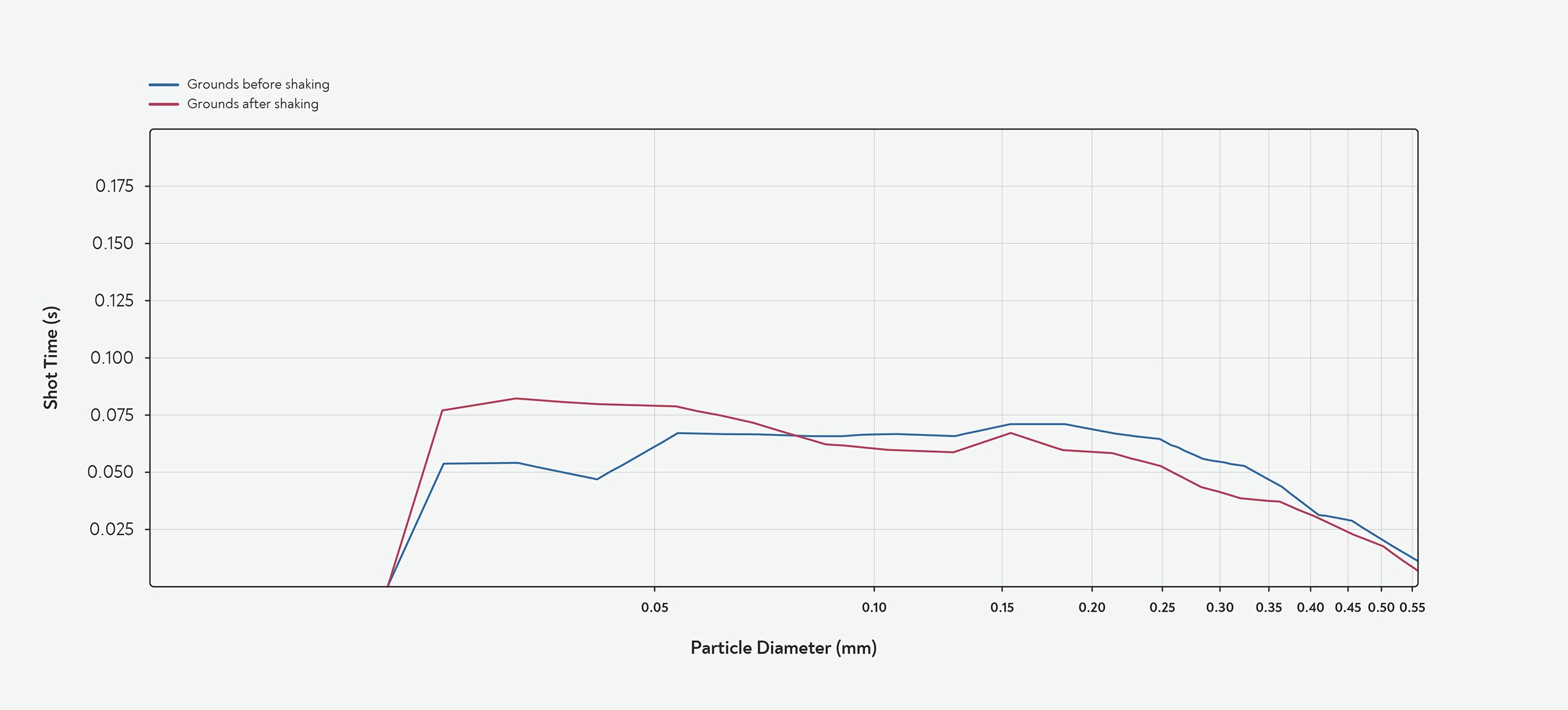

Since the Blind Shaker didn’t appear to be reducing static, we also took a look at the particle size distribution after shaking. As we saw in our previous post on shaking, one possibility for how shaking increases extraction is ‘densification’, a process used when packaging commercial roast and ground coffee. During densification, fines are pushed into crevices in larger particles, creating aggregates that act as larger, rounder particles. If densification was occurring, we’d expect to see a reduction in fines, as the fines form part of larger particles.

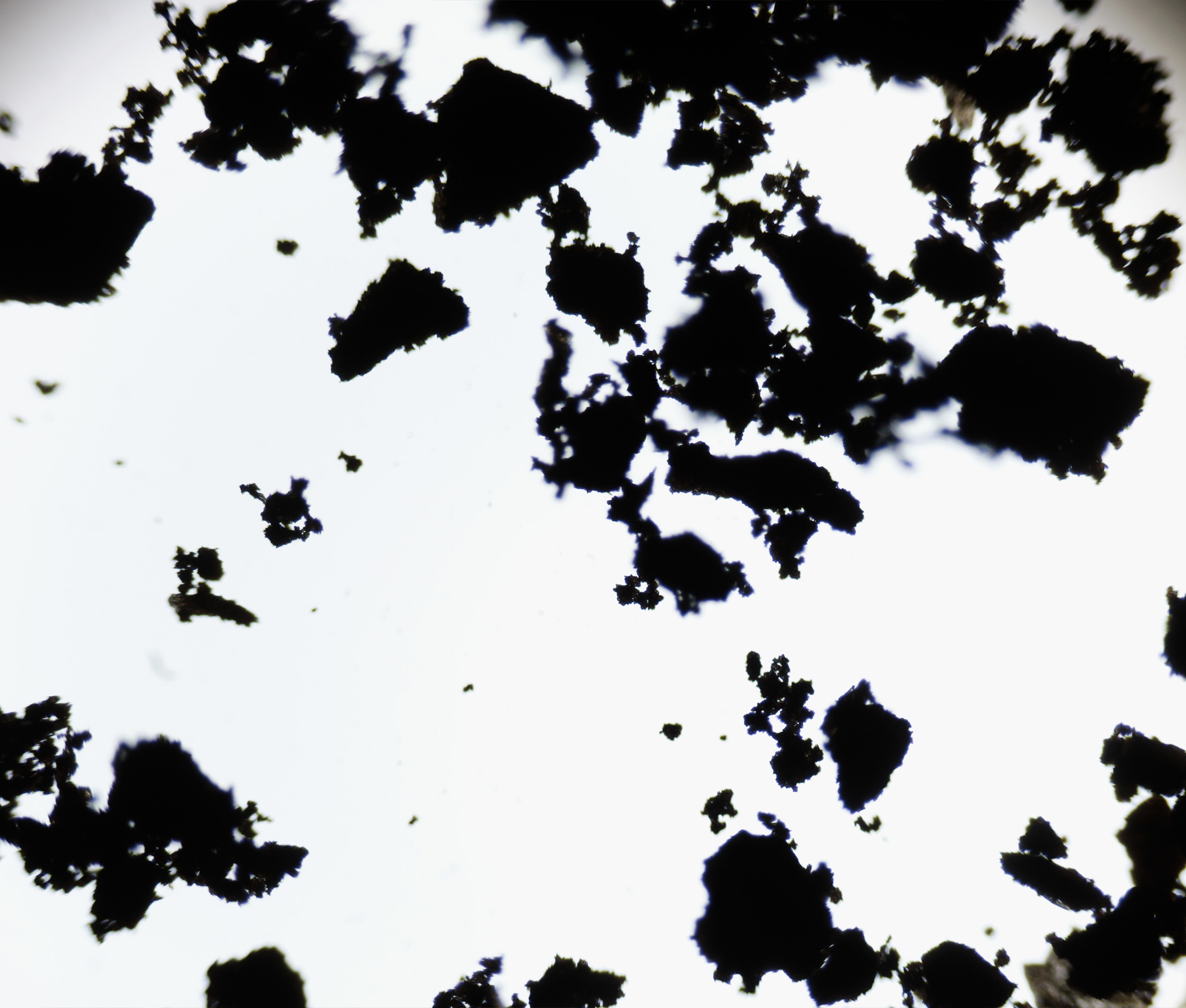

We tested two pairs of samples, laying out the grounds on a grounded piece of tinfoil to reduce static and then spreading them out to photograph them. We used Professor Abbott’s Grind Size Analysis app on the resulting photos. The results were once again surprising. Rather than seeing the reduction in fines that we were looking for, we saw a slight increase in the number of particles below 100µm both times.

Particle size distribution of a sample of grounds before shaking (blue line) and after shaking (red line). Shaking appeared to increase the number of visible fines.

Particle size distribution of a sample of grounds before shaking (blue line) and after shaking (red line). Shaking appeared to increase the number of visible fines.

It was almost as if, rather than causing particles to aggregate, shaking was breaking up particles or aggregates, and making the coffee behave effectively as if it had a finer grind size. But why would shaking have this effect? We asked coffee scientist and roaster Mark Al-Shemmeri to weigh in.

“I don’t see any plausible way shaking will break particles,” he says. “But the way you shake could affect the mixing regime, and could even result in demixing and segregation.” In other words, if shaking is just causing fines to separate out, then that could explain why more of them happened to appear in our sample. We attempted to use the same shaking method that Lance demonstrated in his videos — but it’s possible that some difference in the way we shake affected the results.

Microscope images of ground coffee samples before shaking (left) and after shaking (right). Shaking appears to cause some fines to separate, whereas before shaking they are mostly bound to larger particles.

To truly understand what is happening during shaking will have to wait for analysis with more sophisticated tools. In the meantime, though, we also wanted to see if shaking really helped where it counts — in the flavour of the espresso.

Shaking in the Cup

We asked Miruna to describe her experiences of using the three different methods to make espresso. The effect of shaking on the distribution was evident in the portafilter basket from the very beginning. “We saw numerous clumps and large particles,” she says, noting that there seemed to be a bit less clumping after shaking in the plastic cup than in the Blind Shaker. “The plastic was easier to use, but a notable portion of the grounds still adhered to the bottom.”

Distribution with the Autocomb (left) compared to shaking with the Blind Shaker (right). Miruna found that shaking increased the amount of clumping in the coffee grounds.

Miruna and her team also noted a striking difference in the flavour after shaking the grounds. “The first thing that shocked us about using the Autocomb was the flavour profile of the coffee: it became more bright, the aromas were fruitier, with no more nutty flavour,” she says. By contrast, the shots after shaking tasted far less pleasant. “There was a somewhat powdery texture, and a lack of clarity in flavour across all samples,” she notes.

She was also pleased with the consistency of the results she got after using the Autocomb, as well as the ease of use. “It surprised me that the shot time of all extractions were almost the same,” she says. “At first, my colleagues feared that it would be hard to use during a rush. But after they became more used to it they started liking it! It was more a fear that it seemed complicated at first glance.”

So why did Miruna get such different results to Lance? It’s entirely possible that the particular combination of coffee, equipment, and techniques that she uses favour one distribution method over another.

We already saw an example of this previously with our tests on the Ross Droplet Technique, where we found that static can have opposing effects with different roast styles or different grinders. Darker roasts, and fine particles, are more likely to pick up negative charges, while larger particles and lighter-roasted coffees are more likely to hold positive charges — which can completely change the effect of static in a coffee.

And if densification is behind some of the effects Lance saw, then the choice of grinder could have an impact here, too. Densification is usually applied to coffee that has been ground in a roller mill, which has a different grind size distribution compared with the grounds from a typical espresso grinder, Dr Al-Shemmeri points out. “If you start getting into the super high fines territory where most shop grinders are, it could change the ability to densify — most roller grinders have little fines,” he says. Notably, the grinders that Lance used in his tests (the EG-1 and DF64) both produce relatively few fines for a given grind size, compared to other single-dosing grinders, according to Dr Al-Shemmeri’s analysis of different grinders.

If the choice of coffee or equipment does influence how distribution works, then your results with shaking could well be different to ours. Lloyd Meadows, owner of Tortoise Espresso in Castlemaine, tried shaking in combination with the Autocomb and found that adding shaking to his puck prep routine significantly increased extraction, while having no effect on shot time at all.

Shaking does at least seem to consistently boost extraction in every test we’ve seen, but perhaps the variable effect that shaking has on shot time means that it will also have variable effects on flavour — especially if you also combine it with another distribution method like the Autocomb. For now, the best advice we can give is to try it for yourself, and keep an open mind when it comes to tasting the results.

Disclaimer: Barista Hustle Education is editorially independent from Barista Hustle Tools. We never solicit or pay for testimonials

test

https://x.razorpay.com/auth/signup/?intent=current_account

Anodized aluminum, such as the ww blind shaker, does not conduct electricity. I was dissapointed with the performance of the MHW3-bomber shaker for the same reason, after expecting first that it would decrease static charges but instead seemed to make it worse or at least keep it at the same level.

It would be interesting to test it with a steel cup and lid or untreated aluminium.

Sorry, you already included the test with a steel cup. It shows the effect of static charges well, with increased brewing times from steel -> anodized aluminium -> plastic -> glass. I guess the unanodized aluminium would be closer to the steel cup.