by Cory Gilman

Coffee has a data problem. Or the term ‘data paradox’ might be more accurate.

On one hand, we know more about what’s in our mug than ever before. Emerging technology, coupled with changes in buyer demand, have made traceability (think regions, varietal, flavor profile) a fairly standard offering. Buyers of specialty expect exact altitude coordinates, processing methods, cooperative information, farm characteristics, and even farmer characteristics. With the right search tools, almost any attribute a buyer might want can be pulled down the supply chain and delivered.

On the other hand, despite all the high-tech advancements and emphasis on direct relationships, origin remains an enigma to most buyers. Sure, there are a lot of interesting factoids, but in the grand scheme of things they’re mere tidbits; value-add sprinkles on our latte. Data of substance — statistics that reflect producers’ realities, contribute to informed decision-making, and offer big-picture trajectories — just aren’t there.

To close this data gap and improve the data landscape, we created a collaborative group: the State of the Smallholder Coffee Farmer. We are Heifer International, Lutheran World Relief (LWR), the Agroecology and Livelihoods Collaborative (ALC) at the University of Vermont, and Statistics for Sustainable Development (Stats4SD).

The initiative has two primary components:

- Creation of a consolidated report (available in English and Spanish) discussing key findings

- An open-access digital platform that allows users to explore individual topics and observe trends

Before diving into what the State of the Smallholder Coffee Farmer is, it’s telling to share how and why it came about. It was 2019, and coffee was a few years into a devastating price crisis–exacerbated, or perhaps driven, by a crisis of rural poverty, environmental disasters, migration, and human rights violations. The events unfolding seemed structural rather than one-off events. They appeared to be inevitabilities of a system where farmers are pushed to produce more, prices wildly fluctuate, land becomes less viable and more expensive to work. Consequently, farmers’ incomes plummet and social needs go unmet. These were often discussed as humanitarian issues rather than ones involving systemic injustice.

As international development organizations committed to smallholder farmers, we at Heifer International and Lutheran World Relief felt compelled to take action. We saw a pressing need to foster socioeconomic resiliency and ecosystem supports in order to best serve these farming communities as well as protect the future of the industry. We were already well-versed in the qualitative relationships between coffee prices, livelihoods, land management, and social outcomes. A quantitative assessment was the next step. Given the many multi-stakeholder partnerships, platforms, programs, and studies on coffee, we were confident all we had to do was design a research agenda and start digging.

Oh, how wrong we were. What had seemed like a bottomless pool of information turned out to be quite shallow. We found relatively little information specific to smallholder farmers. Most coffee farmers are smallholders, yet there’s little statistical separation between large and small farms. The data was not separated to individually assess the context of small farms versus medium and large farms; it was mostly conflated, making it impossible to understand what trends and realities applied to which group

While there was a lot of information available about coffee, there was not a lot of information available about coffee farmers. This is a critical distinction. Most information-collecting efforts fundamentally reduce coffee to a crop or commodity, prioritizing data that speaks to yields, quality, trade, supply chains, broadstroke sustainability, and project outputs—principally, data that helps companies and funders make management and production decisions. This emphasis on production and purchasing doesn’t evaluate the contributions, realities, and challenges of smallholders. It isolates coffee’s holistic significance, minimizing producers’ essential role in navigating coffee as a household livelihood, community linchpin, and rural economy and environmental cornerstone. Ultimately, it ignores the farmers’ significance and agency as industry actors. The data design favors the coffee beans over the human beings.

The closer we looked into the data landscape, the less data we found. If our team of development professionals, academics, and statisticians couldn’t find it, coffee producers and cooperatives were certainly hamstrung. We realized that our self-contained research project needed to change its approach, from reactive to proactive, from short-term to long-term. We needed to focus on small-scale coffee farmers, differentiating between their conditions and those of larger, often more resourced producers. Importantly, our research had to take on a philosophical underpinning in addition to a practical one. This meant greater inclusivity in terms of not only who got to access the results, but who got to ask the questions in the first place.

In addition to a written report that could be read, we decided to develop a greater platform, a digital one — a tool that could be flexibly and equitably accessed, allowing reciprocal flows of information.

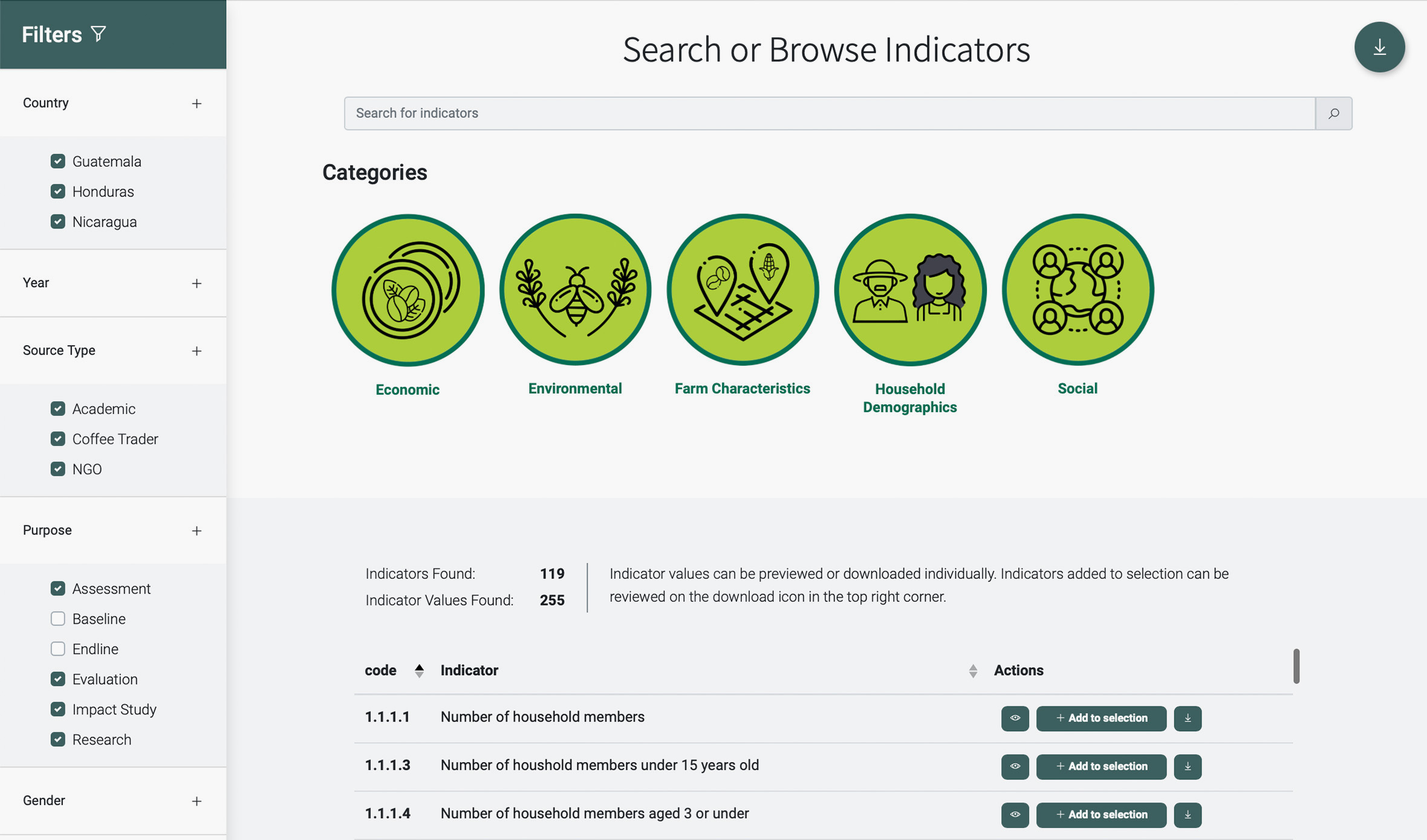

Our initial research study centered on select countries over a finite time frame. Guatemala, Honduras, and Nicaragua represented three of the top smallholder-dominated exporters of coffee to the US; they were simultaneously in the throes of geopolitical events of importance to US foreign policy. The years 2013–2019 marked a crucial period of declining coffee prices, beginning with the coffee leaf rust outbreak and ending with its most recent price crisis, where the market price hovered around US$1/lb. This situation gave us a unique opportunity to draw correlations between smallholders’ financial compensation for coffee production and the overarching socioeconomic and environmental outcomes.

Our inaugural findings were illuminating, if not surprising: although smallholder coffee farmers’ contributions benefit their local landscapes, national economies, and the global industry, we found that most of the farmers are subject to chronic risks and stressors that negatively impact their livelihoods and well-being. These impacts are directly tied to community employment, agricultural GDP, development outcomes, and future conservation goals. The producers, numbering approximately 250,000, typically cultivated coffee under agroforestry systems, thereby generating essential ecosystem services while creating a healthier environment for people and the planet. However, these farmers struggle to stay above the poverty line, achieve household food security, pay workers adequately, conserve biodiversity, and maintain farm conditions necessary for long-term land viability. They are increasingly vulnerable to factors such as rising production costs, price fluctuations, climate change, and political instability. These livelihood challenges, in turn, threaten future coffee production, rural development, sustainable land usage, and even human rights.

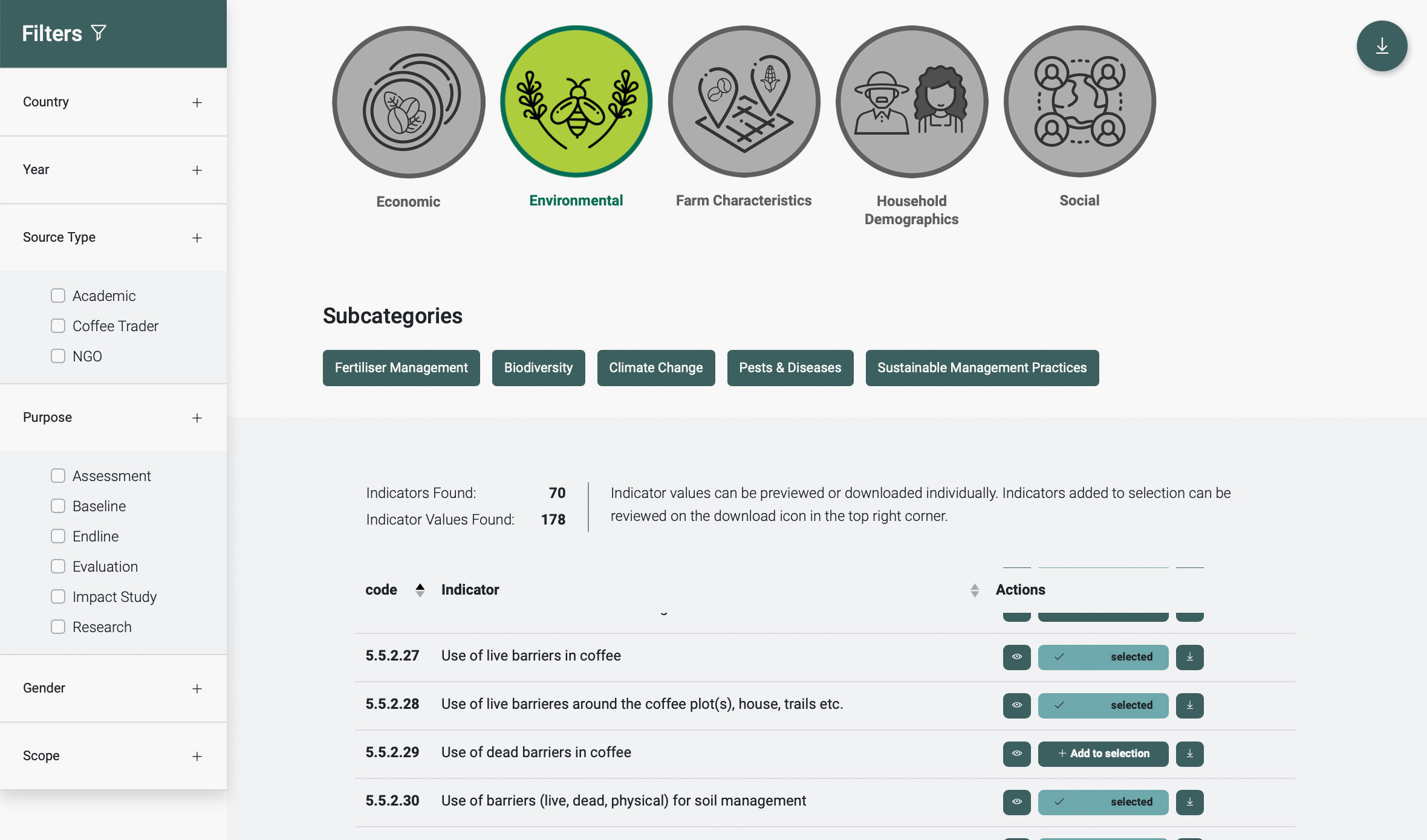

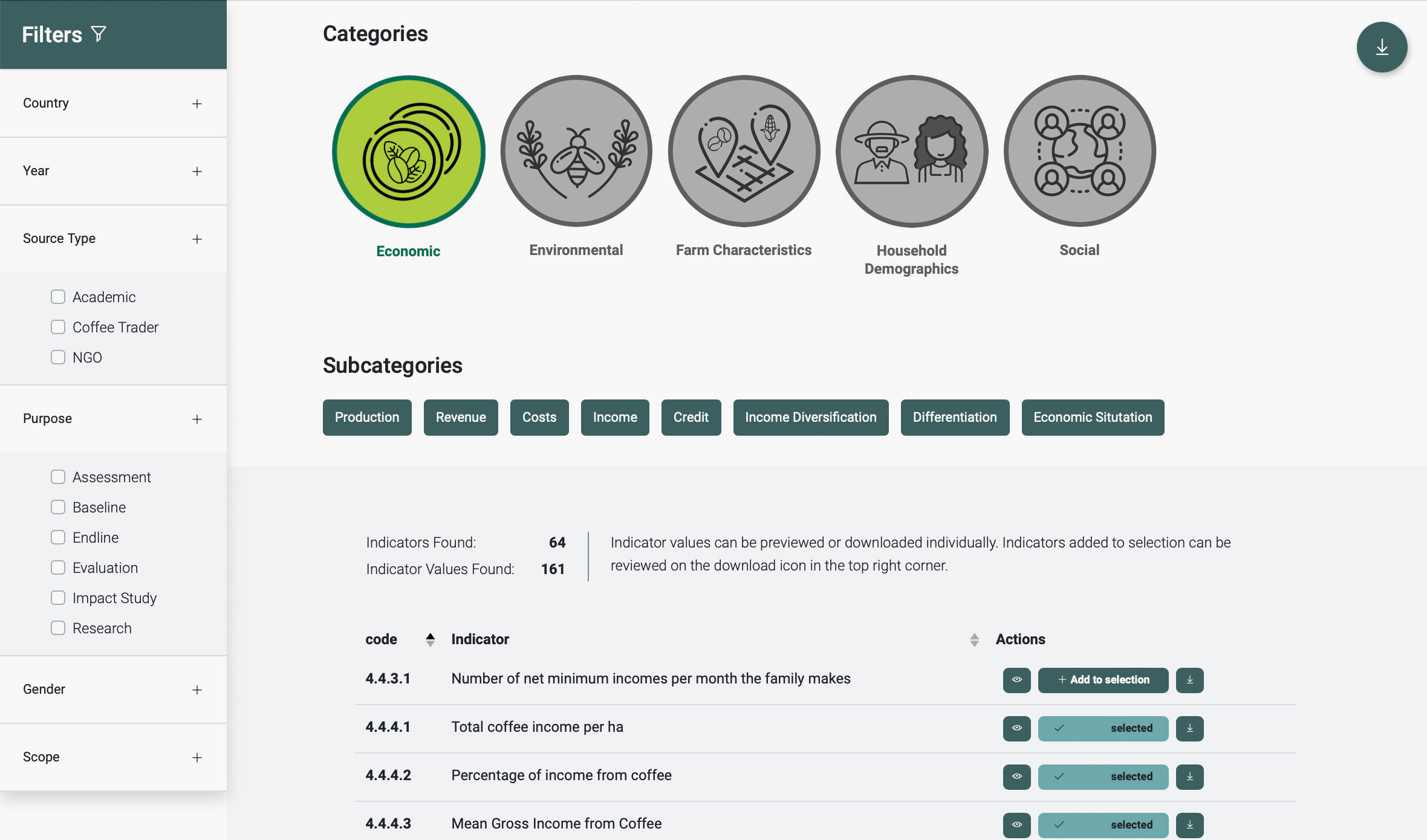

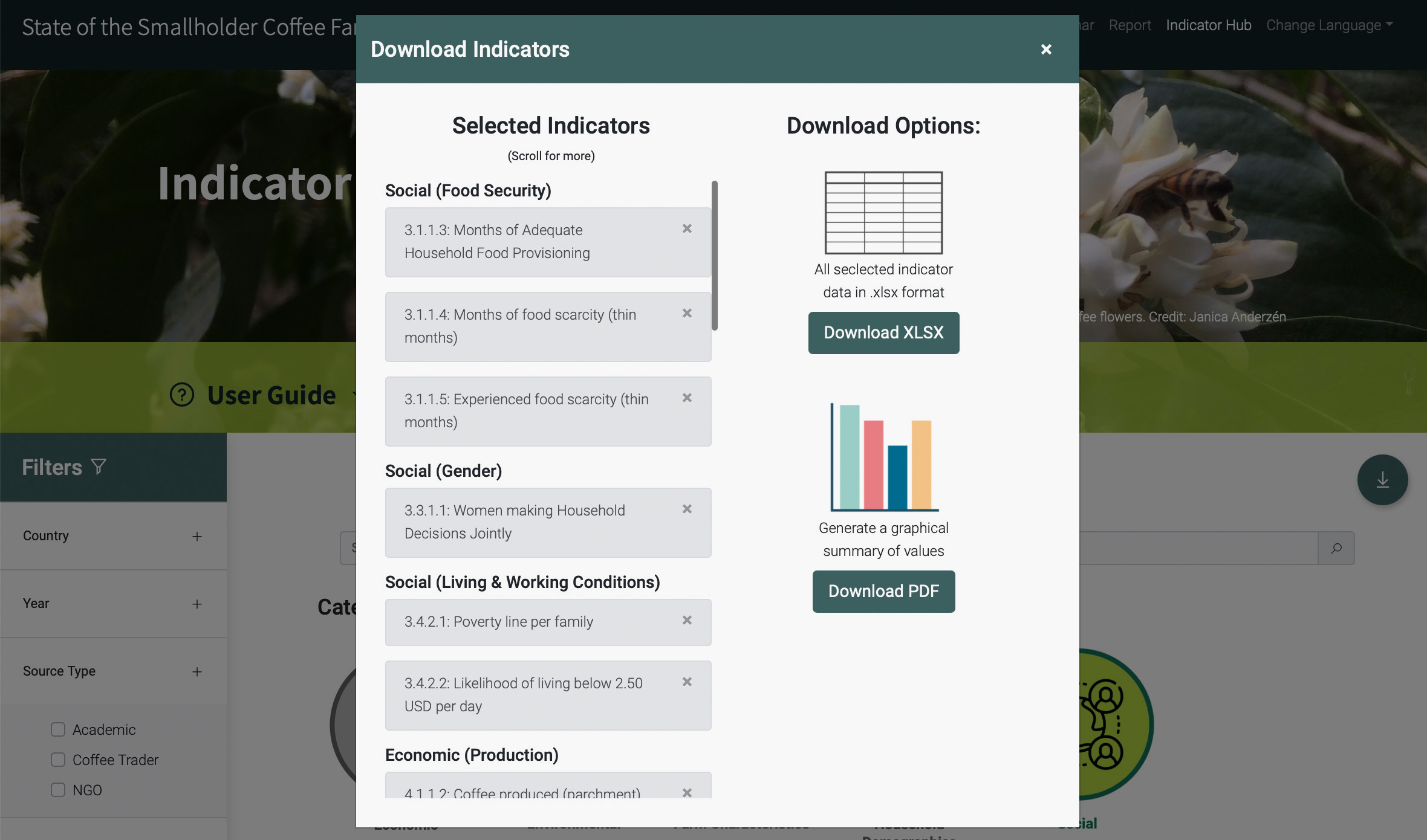

The digital platform we created breaks down information barriers, driving the initiative’s hope of democratizing the data landscape. It is open-access and geared towards interactivity, enabling any user to browse and search by category; the indicators can also be filtered by year, country, gender, source type, and scope. The availability of raw data is particularly important for farmers and farmer organizations who often experience the burdens of data collection but don’t reciprocally reap the benefits of it; the platform permits sharing back of what was learned (about them) and how it’s being used. The interactive nature also facilitates a ‘choose your own data adventure’ that allows users to define their particular scope of interest. Once the available data is pulled for viewing, it can be downloaded as an ExcelⓇ file or PDF along with a graph including details about the indicators and their sources. These details include the site where the data was collected, the intended purpose, and who did the data collection. Essentially, the platform takes information that was previously reserved for academics, institutions, and funders and makes it available to anyone who has a vested interest.

For example, graduate students looking to understand whether coffee incomes contribute to immigration from the Northern Triangle could select years of market prices, relevant economic data such as rural employment, and social indicators such as food security. They could then compare those data to migration rates from the communities over the same years. Conservation specialists seeking to qualify how coffee prices impact sustainable production practices could select appropriate indicators and assess trends. A coffee shop owner hoping to make an informed choice about where to make a financial donation (perhaps to promote gender equity in Nicaragua, agroforestry trainings in Guatemala, or improved nutrition in Honduras) could dig into the available indicators to determine what kind of funding would be most supportive.

Regardless of the platform user’s objectives, this functionality opens the door to self-discovery. It gives each individual who uses it the ability to design a unique learning journey.

The platform has profound implications for future ‘pre-competitive’ information sharing. As previously mentioned, producers are no stranger to having data collected about them, often with a time and commitment cost. Due to multiple factors, development organizations and companies tend to work with the same cooperatives, often seeking to close the same knowledge gaps. Therefore, the same groups of farmers often undergo a similar data-collection process again and again. For example, Heifer International might do a baseline income assessment of a producer group in Huehuetenango; three months later, Lutheran World Relief might do the same. Or perhaps Lutheran World Relief sets out to gauge how much carbon is being stored by a group of smallholders in Matagalpa, while the University of Vermont has a similar query and designs an overlapping assessment.

If researchers agree to collaborate, or at least publicly provide insight into what data is being collected and what the results are, precious resources could be freed up. Imagine how much more we could learn, more efficiently, if we reduced such duplication of efforts. We could save, rather than exacerbate, strains on coffee producers’ scarce time, energy, and opportunity costs. We could achieve so much if we collectively stopped clinging so tightly to intellectual property and data ownership and relinquished tendencies toward tightly guarding information that, arguably, always belonged to producers to begin with.

State of the Smallholder Coffee Farmer is still in its infancy, very much a pilot. But it’s ready to take some new steps.

While initially funded by Heifer International and Lutheran World Relief as a one-time research project with a close-ended report as its sole deliverable, our journey of discovery caused us to revise our goals. We had to pivot. The interactive platform was born. Our partners at The Agroecology and Livelihoods Collaborative at the University of Vermont and Statistics for Sustainable Development dedicated an immense amount of time and personal commitment to ensuring this new endeavor worked within the original budget.

Turning State of The Smallholder Coffee Farmer into a larger-scale, ongoing initiative will require more infrastructure and resources, as well as a year-round team. ‘State Of’ is currently finalizing its plan to refine and scale up, and we are seeking additional funders to help us reach its full potential. As always, data-donors willing to contribute intellectual capital are also deeply appreciated.

If you or your organization are interested in supporting this work in any capacity, we invite you to contact us at [email protected].

About Cory Gilman

As Director of Strategic Initiatives for Heifer International, Cory Gilman is dedicated to advancing economically inclusive, socially just and ecologically sound food systems. Coffee has always held a special place for her; starting as a consumer, her love for coffee (particularly the people who grow it and places it comes from) was solidified during a year learning at the feet of smallholders in Southeast Asia. This experience led her to pursue a Masters in Sustainable Development and Social Enterprise, translating a decade-long career in advertising to international development. Prior to joining Heifer International, Cory spearheaded a social innovation incubator.

1 An agroforestry system mimics how coffee grows in the wild. This promotes many, if not all, of the ecosystem characteristics of a natural forest. They include: storing carbon, generating microclimates, fostering and protecting biodiversity, promoting nutrient cycling that leads to improved soil fertility, and creating inherent resiliency to disease and pests, thus reducing the need for chemical inputs.

0 Comments