The majority of coffee farmers in Guatemala face a challenging and uncertain future. Price shocks, disease outbreaks, and climate change are major threats to coffee farmers all over the world — but Guatemalan smallholder farmers are particularly vulnerable. The modest size of a typical farm and the relatively high cost of production mean that Guatemalan farmers rarely have access to the resources and money they need to protect themselves against these threats.

Picture: Coffee is big business, but it can be hard for small farmers to cover their costs.

Picture: Coffee is big business, but it can be hard for small farmers to cover their costs.

The low prices paid for coffee underlie many of the Guatemalan farmers’ problems. When the price paid for coffee doesn’t meet the cost of production, it’s impossible for farmers to invest in new varieties or in agricultural practices such as pruning, irrigating, and fertilising that can reduce the spread of diseases or offset the damaging consequences of climate change.

‘Many small farmers produce at a loss, with production costs between $190 and $230 per 60 kg bag’, according to the USDA’s 2020 report on the coffee industry in Guatemala. The price paid for coffee in 2019 was $170 to $190 per bag. While Guatemalan coffee earned a premium of $30 over the base price, thanks to its reputation for quality, the difference is still not enough to cover the cost of production, the report notes.

Although the price paid for coffee increased slightly over the course of 2020, it is still too low to support sustainable production for the 2020–2021 harvest, according to Anacafé President Juan Luis Barrios Ortega in an interview for Bloomberg. The effects of climate change and COVID-19 have pushed up the cost of production, and small and medium-size farms are producing at a loss, he said.

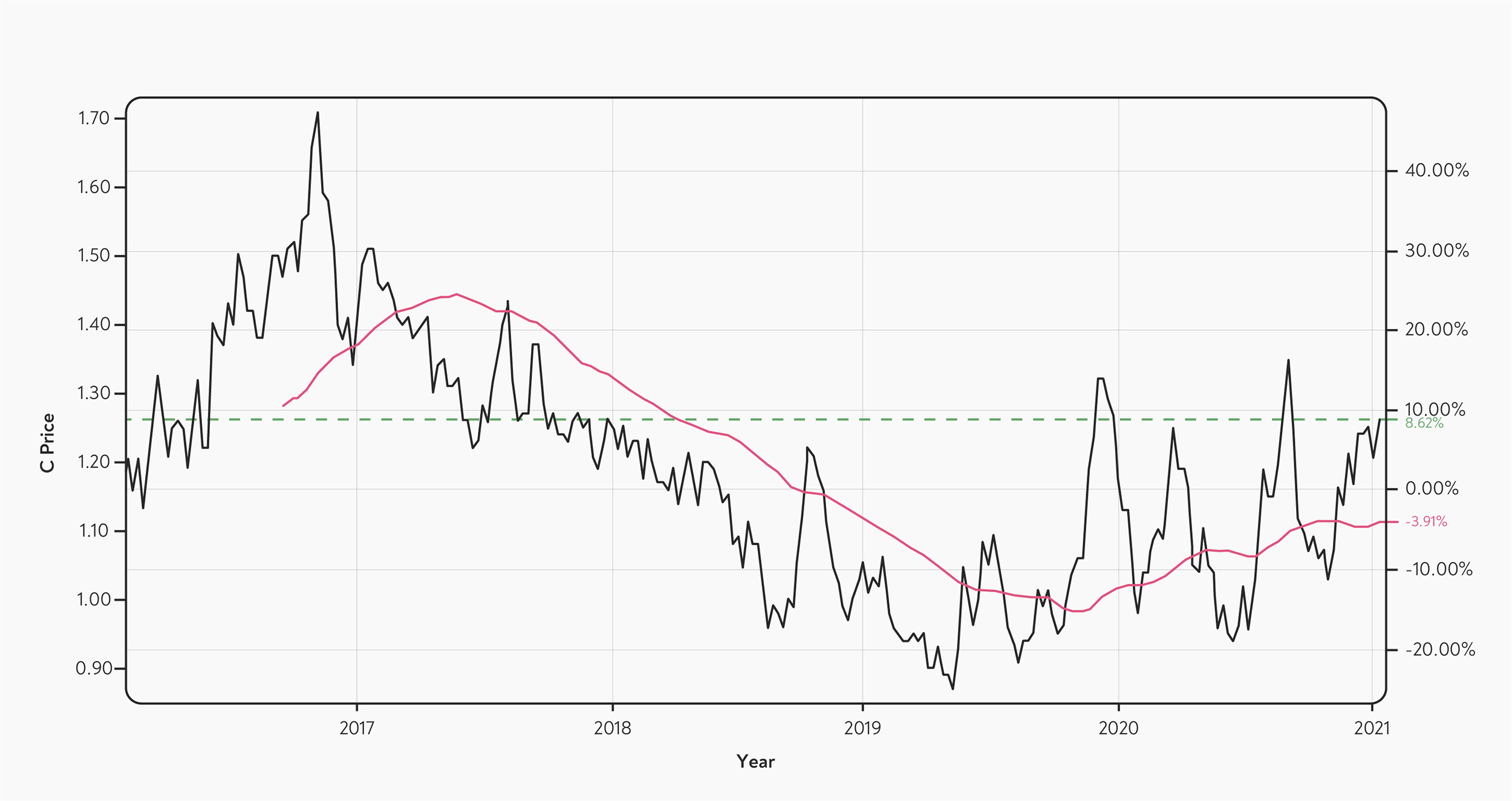

Graph: US arabica coffee futures market (C Price) from 2016–2021. The last year has been characterised by large fluctuations in price, but the average price paid has increased slightly. The red line in the chart shows the 50-day moving average.

Graph: US arabica coffee futures market (C Price) from 2016–2021. The last year has been characterised by large fluctuations in price, but the average price paid has increased slightly. The red line in the chart shows the 50-day moving average.

The drop in coffee prices since 2000 caused large farms in Guatemala to stop growing coffee and switch to other, more profitable crops. This created an opportunity for smaller farms to step in, and these farms now produce nearly all of Guatemala’s coffee. However, Guatemalan farmers still have to compete with large farms on the international market, which have a much lower per-unit cost of production.

‘In some areas of Guatemala, it could take over 1,000 people working one day each to fill a container of 275 bags, each weighing 69 kilograms. In the Brazilian cerrado, you need five people and a mechanical harvester for two to three days to fill a container’, says coffee trader Patrick Installe in a report for Oxfam (Gresser and Tickell 2002). ‘One drives, and the others pick. How can Central American families compete against that?’

For Guatemalan coffee farmers, therefore, the growth in the market for specialty coffee has been especially important. The premiums paid for higher-quality coffee can make the difference between profit and loss (Petchers and Harris 2008).